Hewlett Packard opens doors to its HP Labs UK research base

- Published

Research at HP Labs' UK base is focused on cloud computing, security and advanced display technologies

The year is 2015, and in a government-owned data centre somewhere in southern England thousands of servers are humming away, hard at work keeping the country running smoothly.

In the background, security programs, acting like antibodies in a cyber-immune system, patrol the network which connects these servers together, looking for signs of viruses or other infections.

Suddenly, one of these security programs spots a server acting strangely, and within seconds other security programs descend on it in a swarm.

Each one assesses the situation using its own specialist knowledge and reports back to the data centre's security "brain".

A moment later the decision is made to shut down the server before any infection can spread.

This is the shape of computer security to come, as imagined by scientists at Hewlett Packard's HP Labs research and development facility near Bristol.

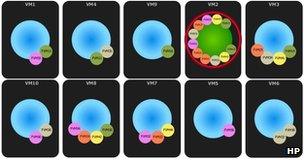

A simulation demonstrates HP's proposed cyber-immune system at work

It is their job to create visions such as this one, and to invent the technology that might be needed to turn these visions into viable products three, five, or perhaps 10 years from now.

Troubled times

Technology and innovation have always been important at Hewlett Packard, ever since the company was formed in 1939 by engineers Bill Hewlett and Dave Packard in Mr Packard's garage.

But the company has had a troubled last few years, with chief executive Mark Hurd resigning in 2010 after a sexual harassment investigation, and his successor Leo Apotheker moving on less than one year later to be replaced by former eBay chief Meg Whitman.

Its plans for mobile computing also proved less than successful: the company bought smartphone-maker Palm in 2010 for $1.2bn (£775m) and launched the HP TouchPad tablet computer powered by Palm's WebOS operating system in July 2011.

But just six weeks later the company announced that it was abandoning the phone and tablet markets in an abrupt strategy u-turn. It has since decided to continue funding WebOS as an open source project.

Grand tour

HP may be down, but it's very far from out, and earlier this month the company offered me the rare opportunity to visit HP Labs, promising a tantalising glimpse into the future of its consumer and business technology.

But visiting HP Labs is no straightforward matter. The company keeps much of the research being carried out at the site under wraps, and tours are carefully planned and managed.

From the moment I arrived I was accompanied by a media relations minder who hurried me from one laboratory or meeting room to the next on a tight schedule, ensuring there was little time to peer through laboratory doorways and chance upon secret research projects.

I now have an idea of how Charlie Bucket felt as he was bustled around Willy Wonka's chocolate factory.

The first stop was a lightning-fast briefing with security expert Simon Shiu who explained HP's vision for a cyber-immune system that used "forensic virtual machines" to hunt for evidence of infections.

"They would be completely autonomous, and if they found something suspicious they would be able to summon more, like a policeman summoning more officers to a crime scene to investigate," he explained.

But do not throw out your anti-virus software yet - like everything at HP Labs these forensic virtual machines are still very much in the development stage, and although prototypes exist they may never see the light of day.

Beyond the cloud

Dr Shiu was quickly ushered away to be replaced by John Manley, one of HP Labs' cloud computing gurus.

Cloud computing includes services such as Google's Gmail email system which run on remote computer servers.

HP's efforts to develop low-powered colour screens have the potential to extend handsets' battery life

Dr Manley pointed out that this is the third recent major development in computing after the internet and the web, and one of his tasks is to ponder and prepare for the next big thing. But what might that be?

"There are no senses on the internet, so the fourth stage is to add sensations: taste, smell, sight, hearing and touch," Dr Manley said.

He has visions of building a vast, planet-wide sensor network using tiny, cheap, sensation detectors which would result in what he calls "the CeNSE": the Central Nervous System for the Earth.

This could be used for everything from wildlife tracking and motorway traffic monitoring to providing earthquake warnings and weather forecasts, he said.

With suitably sensitive sensors, the possibilities are almost endless: one day you might wave your sensor-equipped mobile phone over a plate of food to "smell" whether any of the ingredients have gone bad.

To make CeNSE possible, HP Labs is already developing nanoscale accelerometers and other microsensors.

But what about developing equipment to recreate the tastes or smells these sensors detect?

"You're talking about the HP Stinkjet," Dr Manley replied, somewhat cryptically.

Creating colours

Soon after I was hurried up stairs, along corridors and into a cramped laboratory littered with books, computers, and small screens mounted on circuit boards attached by ribbon cables to pieces of electronics.

This is the lair of Adrian Geisow, HP's display technology expert. He is working on developing the techniques needed to produce bright, high-quality colour mobile phone screens that do not need backlighting, and thus do not drain phone batteries.

Monochrome displays with these qualities are already available in devices such as Amazon's Kindle e-book reader but several companies are competing to bring a colour version to market.

And it is possible that it will be developed not in a hi-tech lab in Japan, South Korea or California, but right here, amid the clutter, in a tiny room in Bristol.

HP's cartoon inhabits almost as cramped as space as its creator

Dr Geisow already has a prototype: a tiny screen displaying a dancing cartoon figure wearing sunglasses which is clearly visible in the ambient light of his laboratory.

No slouching

The final stop was a meeting with Prith Banerjee, the director of HP Labs and a character who comes across as frighteningly efficient and business-like after the friendly informality of the facility's researchers.

He rattles out statistics from the top of his head without a pause: HP is a $130bn company, and it spends $3bn a year on research.

There are six other facilities like the one in Bristol spread around the world, and they employ 500 researchers, involved in 24 projects grouped around eight separate themes.

As I was escorted out I commented to my ever-present minder that the research centre was a very studious environment: why were there no slides and games rooms like the ones which, supposedly, foster free thinking and creativity at research labs run by the likes of Google?

At that point he very proudly showed me an upstairs area which was furnished with a handful of beanbags.

But the telling thing was that none of them were occupied: this is Bristol after all, not California.

- Published8 March 2012

- Published8 March 2012

- Published10 November 2011