The internet is angry - is it winning?

- Published

- comments

The internet community - if there is such a thing - has risen up in anger over recent weeks. The main cause of its concerns have been perceived attempts to curtail online freedom by governments and corporations. So what makes the internet angry - and when does that anger have any impact?

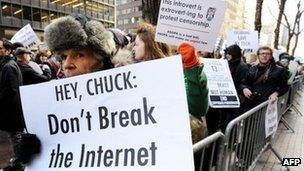

In the United States there was outrage over proposed anti-piracy legislation, Pipa and Sopa, which culminated in a concerted global campaign to highlight the issues by blacking out sites like Wikipedia for 24 hours. And it worked - American politicians who seemed to have assumed that this was a somewhat obscure and uncontroversial issue took fright, and the new laws have been put on the back-burner.

Now it's Europe's turn, with demonstrations over the weekend against another piece of anti-piracy legislation Acta, the anti-counterfeiting trade agreement. (By the way, there is a good explanation of all of the various anti-piracy measures here.) Now, for all the online anger, this is not an issue that has really caught the public imagination in the UK. The crowd at London's anti-Acta demo numbered no more than a few hundred.

But in Eastern Europe, where internet freedoms are perhaps valued more highly, tens of thousands have taken to the streets. And again, politicians who were quietly proceeding with what they thought was an uncontroversial move to standardise copyright laws have been forced to respond. In three countries, Poland, the Czech Republic and Slovakia, they have halted the implementation of the treaty, and the European Parliament now appears less than eager to ratify it.

So, internet 2, governments 0, with online democracy proving its worth? Maybe - although supporters of the various anti-piracy laws would argue that the voices of those who create content which others take for nothing are not being heard in this debate.

And while these online campaigns are proving that they can sway democratic politicians, how powerful will they be against more authoritarian governments?

Consider the case of the Saudi journalist Hamza Kashgari. After using Twitter to express some thoughts about the Prophet Muhammad which some considered blasphemous, he fled to Malaysia, apparently fearing for his life. Over the weekend the Malaysian government put him on a plane back to Saudi Arabia, ignoring the pleas of liberal Muslims in their own country.

We don't know what will happen now to Hamza Kashgari. But his case, on the face of it, looks like a more immediate threat to internet freedom than any anti-piracy laws. So will we see the internet community getting as angry about his case as it has about Sopa and Acta? And if it does will it have any impact on the Saudi authorities?

Looking at Twitter over the last 24 hours, there are signs of a surge of anger against Malaysia, for deporting Hamza Kashgari, and against the Saudi authorities. Some are linking the case to the recent purchase of a stake in Twitter by a Saudi billionaire and asking whether that will affect the social network's view of the affair. But, compared to the rage against anti-piracy measures, this is a fairly muted protest so far.

An angry internet community has discovered its strength over the last year, but there have been few signs that it can challenge governments that are determined not to listen. The fate of Hamza Kashgari could reveal some uncomfortable truths about the battle for online freedom.