Raspberry Pi computer: Can it get kids into code?

- Published

Dr Eben Upton of the Raspberry Pi Foundation shows Rory Cellan-Jones how the computer works

The hope of Britain's future computer science industry is gathered around a tiny device in a school classroom in Cambridgeshire.

The pupils of Chesterton Community College ICT class have been invited to road-test the long-awaited Raspberry Pi computer.

A projector throws the image of what the Pi is generating - a simple game of Snake (available on any Nokia phone near you) - onto a whiteboard.

The atmosphere is feverish as the 12 year olds compete for the keyboard.

Crucially, they are not just playing the game - they have created it by writing their own computer code.

For Eben Upton - the smiling man in the midst of the throng - it is a thoroughly satisfying conclusion to long years of thinking and planning.

"We have been working on the Pi for six years, but we have never tested it with children - the target market," he says.

"In the event, I couldn't have asked for better... they couldn't wait to try it out themselves."

Now his ambition - to provide every child in Britain with their own cheap, programmable, credit-card-sized computer - seems close to realisation.

The Pi's makers want an end to this - traditional ICT lessons spent working on word processors

But what's the fuss all about? After all, the Pi is not that revolutionary in design. It's small - a green circuit board about the size of a credit card.

It has a processor - similar to the one used in many smartphones, so not particularly fast by modern PC standards. It has a memory chip, an Ethernet port to connect to the internet and a couple of USB ports to plug a keyboard and mouse. And that's about all.

You need to supply the keyboard and mouse yourself, and the screen. However, the truly revolutionary thing is the price.

You are now able to order one for just £22 (excluding VAT) - although if the demand is as high as anticipated, it's more likely you'll be on the end of a (very long) waiting list.

Costs are kept down because, according to Mr Upton, there's a lot of goodwill toward the non-profit project. The software is (free) open-source, chip manufacturers have kept their prices low, and all members of the charitable Raspberry Pi Foundation have given their time (and in some cases substantial amounts of money) for free.

The vast majority of the profits will be ploughed back into more devices, improvements and incentives to get children programming.

For many children, £22 is affordable. Twelve-year-old Peter Boughton, who says he wants to write computer games when he grows up, says: "That's eight weeks pocket money for me," he calculates. "I'm definitely going to get one."

Price and scale

Other "bare-board PCs" were available before the Raspberry Pi.

The difference with the Pi is that today's licensing deal with two firms appears to have solved the problems of price and scale: realising the foundation's ambition of providing a unit for anyone who needs one.

The first thousands on release today were funded largely out of the pockets of Mr Upton and his five fellow foundation scientists.

Now they will receive royalties on every Pi sold, and will be able to focus on their main concern - improving what is widely seen as the woeful state of Britain's computer science curriculum.

That was underlined last summer by Google chairman Eric Schmidt, who said the UK - the country that invented the computer - was "throwing away its great computer heritage" by failing to teach programming in schools.

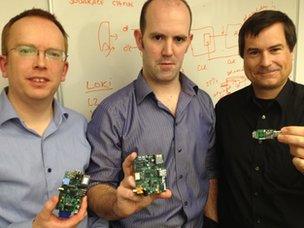

The Pi has changed in development, as the members of Raspberry Pi Foundation demonstrate.

"I was flabbergasted to learn that today computer science isn't even taught as standard in UK schools," he said.

"Your IT curriculum focuses on teaching how to use software, but gives no insight into how it's made."

Mr Upton believes the Pi could provide part of the solution: "We just want to get kids programming. The goal here is to increase the number of children to apply to university to do computer science, and to increase the range of things they know how to do when they arrive."

At Chesterton Community College, Mr Schmidt's criticism might be seen as unfair, because ICT head Paul Williams is not a typical example of an information and communications technology teacher.

Unlike many of his colleagues in the field he knows how to code, and once did it for a living. He also runs a popular programming club after school.

But even he admits the current ICT school curriculum means most of his lesson time is spent in learning how to use software rather than teaching his pupils how to write the code that makes that software work.

He estimates just a tiny fraction of the students he teaches will go on to study computer science at a higher level.

His hunch is backed up by research carried out by the Royal Society, which last month pinpointed a 60% decline in the number of British students achieving an A-level in computing since 2003.

And the Pi itself is very much an academic project - most of its members are, or were, Cambridge University academics who noted a "marked reduction" in the number of students applying to read computer science from the mid-1990s.

But does it matter? The consensus is very much so, as Google's Mr Schmidt put it: "If the UK's creative businesses want to thrive in the digital future, you need people who understand all facets of it integrated from the very beginning."

Squashy rubber

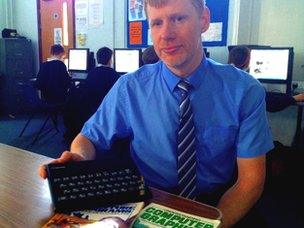

Being a former programmer, Mr Williams has kept his first computer - a 30-year-old ZX Spectrum with squashy rubber keys - and brings it out to demonstrate.

"That's my childhood in a box," he says. "It cost my parents £200, I played the games, but then I wondered what would happen if I changed the program, and altered the game. That's how I started."

It's familiar territory to Mr Upton, who now combines his Raspberry Pi activities with his day job as UK technical director of the computing firm Broadcom.

He says: "We have a theory that back in the 1980s, the computers that people had in their homes were programmable.

"People would buy computers like the ZX or the BBC Micro to play games or do word processing - but then they would find themselves being beguiled into programming.

"That's gone away, because of games consoles and because desktop PCs hide that programmability behind quite a large layer of sophistication."

His theory is backed up by 12-year-old Emily Fulcher who uses her mum's laptop but wouldn't dream of opening it up, or using it to code, "in case I broke something".

For her and millions of other would-be young coders, modern computers are mysterious multi-functional devices, pre-loaded with expensive proprietary software and sometimes fraught with problems.

Children like Emily are terrified to use the family computer for anything other than its pre-ordained function as a costly consumer device.

A Raspberry Pi, on the other hand, is a different prospect: "It's so cheap and you wouldn't be worried about doing different things with it. And if you broke it you could buy another one," says Emily.

'Demotivating and dull'

The Pi launches at a propitious time for Britain's budding computer scientists. Last month, Education Secretary Michael Gove announced he was tearing up the current ICT curriculum, which he described as "demotivating and dull".

He will be replacing it with a flexible curriculum in computer science and programming, designed with the help of universities and industry.

Mr Gove even name-checked the Pi, predicting that the scheme would give children "the opportunity to learn the fundamentals of programming with their own credit card-sized, single-board computers".

Pride and joy: Mr Williams recalled programming on his ZX Spectrum as a child

Mr Williams cannot wait: "It (the Pi) is going to bring an affordable device to students, so they can look at developing something themselves. They will have a device they can hold and feel and look at.

"I can imagine them saying: Let's see we if can get it work. How does this work? How can I get it to do this? It's brilliant. It really gets them thinking how to do stuff for themselves."

But the Pi does have its doubters, like technology journalist Simon Rockman, who recently wrote: "Today's kids aren't interested (in coding). The world has moved on…what makes their applications work or what is inside the black box is as interesting as the washing machine or vacuum cleaner.

"I've long thought that there is a bubble of tech; people of my age are more techie than their children."

Coding incentives

Mr Upton remains unfazed. Now the Pi is launched, he and his colleagues are already looking at new ways to incentivise children into coding. There are plans to offer "very significant" prizes - perhaps totalling £1,000 or more - to children who impress the foundation with original programming.

And the foundation is already talking to exam boards and educational publishers about incorporating the Pi into lesson plans.

Mr Upton is convinced that the Pi will prove to be fun.

He says: "This is about getting kids to engage creatively with computers: doing interesting things. And to be fair that doesn't even have to be programming: it can be art, it can be design, using computers in a creative way.

"What we saw at the school was that as soon as the children were given access to something they could play with, they started playing with it without direction, without someone trying to lead them by the hand.

"Often what they tried would go wrong, but they learnt something from whatever mistake they made."

- Published29 February 2012

- Published13 January 2012

- Published8 March 2012