GAME over on the High Street?

- Published

- comments

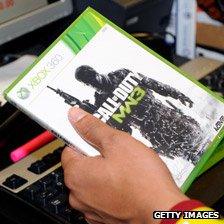

Last November Call of Duty: Modern Warfare 3 became the fastest selling entertainment product ever, with excited gamers queuing at High Street stores to pay over £40 for their fix. Spool forward to Monday, and the UK's best known games retailer Game Group has told its investors their shares may be worthless as it struggles to survive. So how do we reconcile these two pieces of news?

First of all, despite the success of blockbusters like Call of Duty, it has been a tough 12 months for the games industry - or at least for those parts of it relying on traditional console games. With no major new console launches - the year was described by Game Group as a "cyclical low point in the industry" - there has been a shortage of reasons for gamers to restock with new titles.

UKIE, the trade body for the UK games industry, described 2011 as "a challenging year for the boxed product video games market" with sales down 7% on the previous year. For High Street retailers like Game, it was probably even more challenging - the UKIE figures include online sales from the likes of Amazon and Play.com, and anecdotal evidence suggests that this is where gamers are directing more of the cash they spend on console games.

And even when a hot new title comes out, High Street shops find that their profit margins are under threat from supermarkets offering cut-price deals. The games industry site MCV quoted one independent firm, external describing the discounting from supermarkets and online retailers as "serious and suicidal".

But what makes the outlook for any company trying to sell games on the High Street even darker is the fact that the digital revolution is finally sweeping through this industry. The industry has been able to hold on to physical sales for longer than seemed likely, but now digital downloads are gradually taking over, and, just as in the music business, that is leaving casualties behind.

Blockbuster games are money-spinners

From digital distribution platforms like Steam to smartphone apps and social networking games, there are all sorts of new ways for gamers to get access to the industry's products - and at a much lower price than a boxed game. For developers and publishers who learn to adapt, that does not have to be bad news.

Electronic Arts, the giant American games firm, revealed recently that a third of its revenues came from its digital business, boasting that it was now the number one games publisher in the Apple App Store. Other firms are working out that hooking gamers into a lasting relationship with a title that involves buying virtual goods and add-ons may produce more revenue than the original boxed product.

None of this, of course, is much use to a retailer like Game. In May 2008, its share price peaked at £2.96, as the Wii, the XBox 360 and Sony's PlayStation 3 created a booming market for console games. Today, the shares are trading at about 1p - which says the market has recognised that the firm is worth virtually nothing.

In under four years, the idea of popping down to the High Street to buy a new game has become very old-fashioned - although I suspect that Game stores will currently be busy with youngsters spending those gift vouchers they got for Christmas.

What is surprising is that it took so long for such a digital industry to move away from the physical world.