Innorobo 2012: Is the dream of having a robot companion over?

- Published

Kibo's body includes a face-recognition camera and voice-recognition microphone

Say hello to my little friend: Kibo is just under 4ft (1.2m) tall.

If you ask him nicely, he will pass you a present, give you a hug, or enjoy a bit of a dancing to Lady Gaga.

He can display 10 "realistic" human emotions - such as surprise, anger and happiness.

And to quote a bemused onlooker, he looks like he is "on something".

Unfounded substance abuse suspicions aside, Kibo's highly sophisticated innards - based on Honda's popular Asimo robot - are the latest step towards solving one of technology's greatest mysteries: can we make a robot that acts like a human?

The South Korean android is on show at Innorobo, Europe's largest robotic event, held in Lyon, France. Over 50 exhibitors from around the world are taking part, displaying the results of years of hard work, and millions of pounds in funding.

Trust and interact

It is Kibo's first trip outside its home country, and judging by the permanently startled look on its shiny face, it is an enlightening experience.

The second Innorobo summit is 50% bigger than last year's event.

It also proves memorable for Emi, a five year-old French girl. With a little forceful encouragement, she steps forward to accept a "gift" from the robot during a crowd-pleasing demonstration on the exhibition floor.

"It was so pleased to with you," Kibo tells Emi, in broken, robotic English. "This is for you."

It then judders towards her, carrying - in what can only be described as a "choke hold" - a small cuddly toy animal.

It is a demonstration of what represents one of the industry's biggest hurdles.

How can we get people - particularly the very young and the very old - to trust and interact naturally with chunks of metal and plastic? What will it take for Kibo to be Emi's friend, rather than the subject of her nightmares?

"One of my big convictions is that the difference between a machine and a robot is the emotional reaction that you can elaborate with humans," event organiser Bruno Bonnell says.

As co-founder of the legendary video games maker Infogrames, Mr Bonnell has a reputation for recognising emerging tech trends. He now runs his own robotics firm - Robopolis.

He argues the industry should perhaps look to recreate simpler, smaller tasks - areas in which robots can help humans in a specific way to achieve a goal.

Robopolis is the French distributor for US firm iRobot's Roomba - one of the very few commercially successful mass-market robots.

Since its introduction in 2002, more than seven and a half million of the automatic vacuuming machines have been sold. The latest version, called the Scooba, is able to wash hard floors.

Speaking to the BBC, Mr Bonnell touches upon one of the biggest elephants in the room in the humanoid industry: perhaps it is time to give up the dream of a robo-companion.

"Robots have long been fantasised as being clones of humans," he says.

NASA uses Robothespians to meet and greet visitors at the Kennedy Space Centre

"It's probably still far away from execution, and perhaps a little vain because we're not so efficient after all for the majority of tasks."

'Let go'

His opinion is backed up by Will Jackson, director of UK-based robotics firm Engineered Arts Limited.

Mr Jackson is in town to market his charismatic Robothespian, an android that can act out plays - quite convincingly so, it must be said.

Unusually for humanoid development, the Robothespian is commercially viable, sustaining the company without the need for research grants and handouts.

But, despite creating one of the most sophisticated and life-like humanoids at the event, Mr Jackson is remarkably frank about the company's intentions.

"We do not care at all about functional utility," he tells the BBC.

"This will never clean the house, it will not clean the floor, it will never do the dishes.

"That kind of notion for a service robot we think is completely wrong. It will never be a viable economic thing to have this kind of robot performing domestic service functions. Forget about it."

Human characteristics can be remarkably complex to code. Programming even simple tasks - like giving someone a ball - involves a multitude of subtle stages, such as exactly when to reach out, when to let go and how hard to hold the item.

"It would cost $5m (£3.2m) to design and create a robot which was capable of flying and landing an aeroplane," remarks robotics expert Tim Field.

"But even if you gave me $50m, I could not make something that could naturally reach into my pocket and take out my keys."

Mr Jackson questions why we would even want to try.

"It's the Frankenstein story," he says. "Man plays God. We all want to see a walking machine that reflects ourselves."

Happy Paro

Attendees at Innorobo are gifted with a wealth of humanoid distractions.

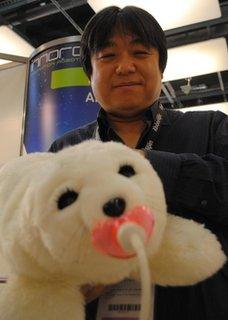

Paro has been used to relax patients and improve motivation

And yet, among the dancing FutureRobot, and the simply freakish iCub, it is hard to ignore the cheerful "churp churp" of Paro, the furry mechanical baby seal developed by renowned robotics engineer Takanori Shibata.

Since its introduction in 2003, Paro has been used in some of the most unexpected situations for a robot: comforting Japanese tsunami victims, delicately helping dementia patients and even forming part of a welcoming party for President Barack Obama.

It is Paro - not "The Paro" as this journalist is swiftly reminded - that tugs at the emotions of passers-by. And, unlike the androids - which people stare at or scurry away from - Paro is embraced by children and suited businessmen alike.

"People can easily touch the body of Paro and feel comfortable," Mr Shibata says.

"Human-type robots, these metallic, mechanical robots, are visually very interesting. But for ordinary people it's not natural. A lot of people have a fear of interacting with such a mechanical robot."

It is perhaps here where our future relationship with robots lies. All of the humanoid robots at Innorobo are in search of one crucial attribute - to draw an emotive reaction from their user.

It is telling that it is only Paro, arguably the least human of all the robots on show, that achieves the goal.

- Published14 March 2012

- Published8 March 2012

- Published27 November 2011