Can computers have true artificial intelligence?

- Published

Is it possible to create true artificial intelligence and, if so, how close are we to doing so, asks mathematician Professor Marcus du Sautoy.

It was while I was making my last BBC TV series, The Code, that I bumped into a neuroscientist I knew.

"Have you heard the news about Watson?" he asked me.

I wasn't quite sure what he was referring to. A new release of Sherlock Holmes? I looked confused.

"Watson beat the world champions at Jeopardy last night," he added.

Jeopardy is an American television quiz show which tests general knowledge. But I could not understand why a professor of the brain was interested in it.

But then he revealed that Watson was not a person, but a computer. Watson's triumph, he believed, represented a hugely significant moment for the field of artificial intelligence (AI).

Ever since Alan Turing's seminal paper back in 1950 asking whether machines could ever think, scientists have been striving to create machines that can rival our intelligence.

Trivia challenge

There are a series of challenges that many in the AI community regard as key hurdles that need to be cleared on the way to realising Turing's dream.

And getting a computer to beat the best the world has to offer at the quiz show Jeopardy is one of them.

That may seem a ridiculously trivial goal, but actually at its heart is something the human brain does extremely well.

Take the quiz question: "What element, atomic number 27, can precede 'blue' & 'green'?"

The human brain is able to negotiate natural language and quickly tap into the huge database stored in our memory to retrieve the answer "cobalt".

Computers have become increasingly good at this skill. You just have to think how search engines now seem to know exactly what you are looking for despite minimal input from you.

But tweaking the mathematical algorithms that run these search engines to demolish the world champions of Jeopardy marked the moment when computer intelligence left human intelligence in its wake when it comes to accessing information.

And that is not the first time computers have met a key test of AI. Back in 1999, IBM's supercomputer Deep Blue beat the reigning world chess champion Gary Kasparov.

Requiring deep logical analysis of the implications of each chess move, this was perhaps the easiest of the goals for a computer to achieve. Logical thinking is what a computer does best.

The Turing Test

The benchmark for the success of AI that Turing suggested in his original paper of 1950 was about communication.

If you were talking online with a person and a computer, could you distinguish which was the computer?

Since we can only assess the intelligence of our fellow humans by our interaction with them, if a computer can pass itself off as human, should we then call it intelligent?

There are some very good candidates out there that are getting close to passing The Turing Test, including this one,cleverbot, external.

Interestingly this hurdle is more and more being regarded by those in the field of AI as a red herring.

Even if a computer passes the test, it does not mean it understands anything of the interaction.

In fact I was recently put through a thought experiment called The Chinese Room devised by philosopher John Searle, which challenges the idea that a machine could ever think.

I was put in a room with an instruction manual which told me an appropriate response to any string of Chinese characters posted into the room.

Although I do not speak Mandarin, it was shown I could have a very convincing discussion with a Mandarin speaker without ever understanding a word of my responses.

The Chinese room problem

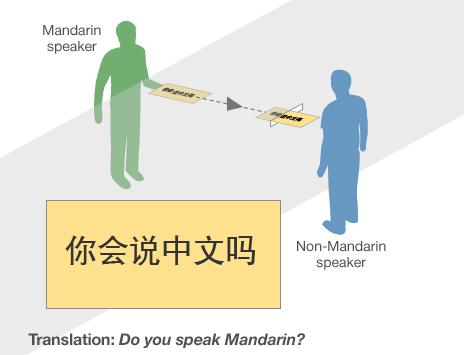

A message is sent to a non-Mandarin speaker in "The Chinese Room"

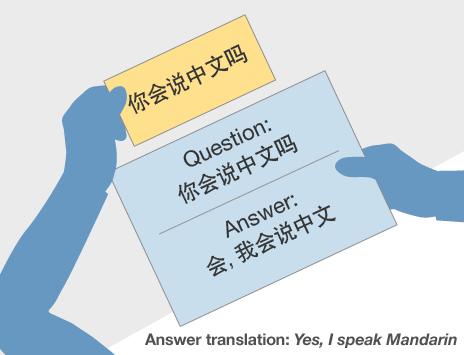

Armed with an instruction manual of possible questions and answers, the non-Mandarin speaker is able to match the characters and select a response.

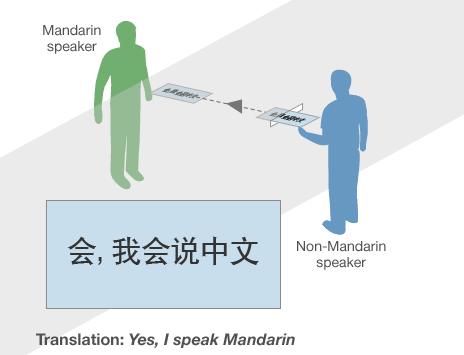

The Mandarin speaker believes he has been talking to another Mandarin speaker. But the person in "The Chinese Room" has no idea what he has said.

Searle compared the man in "The Chinese Room" to a computer reading a bit of code. I didn't understand the Mandarin so how could a computer be said to understand what it is programmed to do.

It's a powerful argument against the relevance of Turing's test. But then again, what is my mind doing when I'm articulating words now?

Aren't I just following a set of instructions? Could there still be a threshold beyond which we would have to regard the computer as understanding Mandarin?

Computer vision

Probably the biggest challenge for AI is to match the human ability to process visual information.

Computers are still miles away from getting anywhere near how amazing the human brain is at taking in and interpreting visual images.

Just think about those warped words that you are asked to type when a website wants to confirm it is interacting with a real person rather than an automated attack which could spam the system.

It is a curious reverse-Turing test where the computer is now trying to distinguish between a human and a machine.

Humans are able to unravel the warped-looking letters while a computer is incapable of pulling the mess apart.

It's a striking example of just how bad computers are at processing visuals. It's not just the AI community that regard this as a central challenge in realising artificial intelligence.

Given the number of CCTV cameras that are watching our every move, security firms would love to crack this conundrum. Currently they still have to employ humans rather than computers to monitor the images and pick up on any suspicious behaviour.

Computers tend to read a picture pixel by pixel and find it hard to integrate the information.

It seems that we are still a long way from creating a machine that can rival the 1.5kg of grey matter between our ears. But we should remember that it did take us millions of years of evolution to realise the extraordinary machine that is our human brain.

Marcus du Sautoy is the Simonyi Professor for the Public Understanding of Science at the University of Oxford. He presentsHorizon: The Hunt for AIon BBC Two at 21:00 BST on Tuesday 3 April. Watch online afterwards (UK only).