Medical device hack attacks may kill, researchers warn

- Published

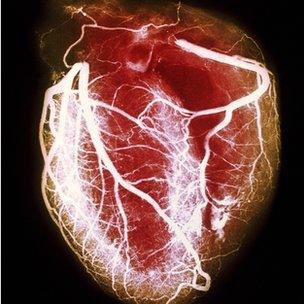

Many people are only alive because a medical implant keeps their heart ticking

Karen Sandler has a big heart. And that's not just because she is head of the Gnome Foundation - a non-profit community group dedicated to making and giving away free software for PCs.

She has an enlarged heart thanks to an inherited medical condition known as hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) that makes the walls of her heart very thick so the organ is bigger and stiffer than normal. It also puts her at risk of sudden death.

Every year, she said, there is a 2-3% chance that her heart would stop beating. The risk is cumulative so the older she gets the greater her chance of HCM proving fatal. Thankfully, medical science can head off the growing threat it poses.

Dealing with HCM involves implanting a defibrillator that will shock the heart into activity if it stops working.

Ms Sandler's unique skills made the process of getting an implant trickier than it might be for others. Ms Sandler is a lawyer, a programmer and a passionate advocate of open source software.

Open source software, as its name implies, can be inspected by anyone to see how it is put together.

That ideological bent meant she was keen to find out about the computer code running on any device that might be inserted in her body.

Unfortunately, she told the BBC, the implant's maker would not reveal its software. Its reassurances about the code's integrity did not help.

"Knowing what I know about software I'm sure it'll have bugs," she said.

Ms Sandler was also worried about the fact that increasing numbers of implants broadcast information all the time. That wireless link was a step too far for her.

"We're just trusting these computers though there's greater access to them than ever before," she said.

Ms Sandler chose an older defibrillator that communicates via magnetic coupling and only gives up data when interrogated directly.

"I will know if someone is changing it," she said.

"Knowing that something has to be put on my skin to do that is a lot more reassuring."

Dial-a-dose

The research of Prof Kevin Fu suggests her fears might be well grounded. As a computer scientist at the University of Massachusetts Amherst he has carried out research for the US government on the trustworthiness of the code in medical devices and implants.

"Without software many medical treatments could not exist," he said, "and implants do help patients lead more normal and healthy lives but software brings with it inconvenient risks."

Many "preventable deaths" had occurred, he said, because the code inside medical devices at bedsides in hospitals or inside patients was not stringently checked. Safety and security were too often an afterthought, he added.

In one case, he said, too high a dosage of a drug was administered via an infusion pump because the fields denoting hours, minutes and seconds were not labelled on a control screen.

A subsequent update labelled the fields correctly. Increasingly, Prof Fu said, such code faults were only being caught when they caused problems.

"There are certainly lives at stake when software fails in a medical device," he told the BBC. "What's important is to design these out."

Risks emerged, he said, when devices encountered a situation for which they were not designed. Such a situation was much more likely to occur as medical devices became more complex.

"It's not that device manufacturers are not thinking about these problems," Prof Fu said.

"It just that the methods and techniques to prevent these problems are not being widely used."

The risks were likely to increase significantly with devices that use radio links to give or receive data. Many devices did this now, he said, to help doctors find out how a patient had been doing between check-ups.

Radio risk

Researcher Barnaby Jack at security firm McAfee has shown that this open communication poses risks. In just two weeks of work, Mr Jack found the radio signal used by an well-known insulin pump and discovered how to hijack them to compromise the device.

The result is an attack tool that could scan a crowd for people fitted with pumps and then transmit a signal that told any implant to dump its entire cartridge of insulin into its host's bloodstream.

Hack attacks on more general computer systems have reached epidemic proportions

The huge dose of insulin would likely prove fatal, said Mr Jack. He also discovered a way to over-ride the safeguards in the pump that make it vibrate when insulin is being delivered.

"It would be hard for them to know what's going on," he said.

By adding radio links to insulin implants, the manufacturers had massively increased the "attack surface" available for exploitation.

"They are low power and and have little code on them so there's no real room to implement any encryption or authentication," he said.

Early warnings

In the UK, the types of devices studied by Prof Fu and Mr Jack are overseen by the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency.

"We closely monitor the safety and performance of all medical devices and take action to ensure the safety of patients," said an MHRA spokesman.

Professor Panos Vardas, president elect of the European Society of Cardiology, said the proprietary protocols used by implants protected against interference.

He described the likelihood of an illegal manipulation as being "extremely remote".

"We are not aware of any security breaches involving patients implanted with cardiac devices," he said.

Mr Jack said he had no plans to publicly release his research results.

"My purpose was not to allow anyone to be harmed by this because it is not easy to reproduce," he said. "But hopefully it will promote some change in these companies and get some meaningful security in these devices."

Prof Fu said his work was motivated by a similar impulse.

"Medical devices are reaching a stage where there are problems, there are vulnerabilities but there is a perceived lack of threats," he said.

"My worry is that we will learn about how to protect these systems only after an incident occurs and I would much rather see these problems addressed before there is such an incident."

- Published8 March 2012

- Published8 March 2012

- Published18 November 2011