Life after Firefox: Can Mozilla regain its mojo?

- Published

Mozilla knows it needs to diversify its income possibilities if it is to survive

Mozilla Foundation president Mitchell Baker is sitting on a ticking time bomb.

The survival of her company, which pledges to make the web a better place, is at the mercy of one of its main competitors, Google.

If you haven't heard of Mozilla, you almost certainly know - and perhaps use - its most famous product: the Firefox browser.

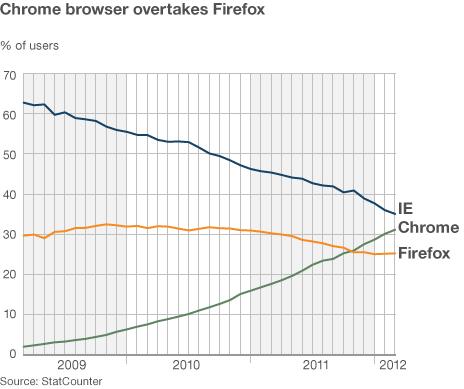

Since 2002, it has been steadily gaining market share against Internet Explorer (IE), Microsoft's pre-loaded, oft-criticised equivalent.

It now has about half a billion users, a huge number of which are evangelists for the software. Many even help create it - it is one of the largest open-source projects on the net.

Google likes this. So much so, they pay Mozilla millions of pounds every year to secure a piece of prime real-estate on Firefox's default homepage encouraging users to perform a Google search.

This investment is believed to represent about 85% of Mozilla's entire income.

Mozilla loves that, no doubt, but can they trust it?

Mitchell Baker tells the BBC it is important for Mozilla to diversify its income

"If for whatever reason the Google deal wasn't renewed, it would be difficult," admits Ms Baker in an interview with the BBC.

"We have a good amount of retained earnings, and we manage it that way so that we would have a long period to adjust, but that's not the situation you want to be in."

Why would Google pull out or scale back its contribution? Well, unlike in the past, when Firefox was the only real competitor to IE, the browser war is now a three-horse race. For Google, with its highly popular Chrome browser, Mozilla has gone from being a partner, to one of its competitors.

Beyond the browser

In November last year, against a backdrop of uncertainty and worry, Google renewed its deal. The terms were not made public and, until we see Mozilla's next public accounts (due soon, they say), we won't know how much money Mozilla is currently earning.

According to some measures, Chrome overtook Firefox's market share in January. If this trend continues - and there's little to suggest it won't - the value of the Google-Firefox deal will begin to sag.

If Mozilla is to survive, it needs a new major revenue stream.

"We are not currently diversified, revenue wise," Ms Baker admits.

"With Firefox we have a sustainability model so we can pursue our public benefit goals effectively.

"It could be a good sustainability model for many years to come, but it's not good to rely on that. As we pursue these new initiatives, we do and will look for new ways to make them sustainable as well."

These new initiatives mean that Mozilla has been forced to look well beyond the browser.

The internet is a very different place today than it was when the first Firefox - named Phoenix until a trademark wrangle - came onto the scene.

Back then, about 90% of computer owners accessed the web using IE. It was - by Microsoft's own admission several years later - vulnerable to attack.

"We came out of a history of abuse," reflects Ms Baker.

"Firefox succeeded in part because of the abusive behaviour that came through IE - spyware, malware, ads. That's part of our history."

Is there still "abuse" on the internet?

"If you think about the architecture of the web, there's no real place that says 'I'm at the centre'.

"The world is doing more things on the internet today, and the browser is no longer adequate to build that kind of user control.

"The phrase I like to use is user sovereignty. I'm the human being. I should be in control.

"It should not be that I buy a machine and that something else is controlling it - because then I become the object."

'Explosive innovation'

In January Mozilla announced Pancake, billed as an effort to re-think the way we navigate and manage ourselves on the web.

It offers, in Mozilla's words "occasionally crazy ideas", such as doing away with the URL system (or at least, hiding it from view) and, crucially, creating a cloud-based framework that allows us to carry and manage our personal data wherever we go.

"Think of it more as your dashboard," explains Ms Baker.

"We're not looking to become Facebook, or LinkedIn and all these other sites. We're not trying to displace those sites - we're trying to make a place where, for example, it could say: 'Application X wants this kind of data'."

She worries that our shift towards adopting mobile apps is fragmenting the control we have of our lives. The internet was meant to be connected, she says - not siloed.

"We really do want to encourage developers to develop across devices, using the same kind of power and explosive innovation and freedoms that the web has given us over the last 15 years."

Ms Baker knows that if projects like Pancake are likely to succeed, they will need not just developer backing, but the same mass-market adoption that made Firefox such a success.

But for a company that has dined out on a single, highly-monetisable project, such a dramatic change of direction could prove difficult.

"We've always been more than Firefox, but we haven't talked about it that much," Ms Baker says.

Goodwill

Fortunately for Mozilla, it is free to develop a good idea first, and worry about the money later.

"The reason for the other initiatives is not driven by revenue," Ms Baker says. "It is driven because we cannot fulfil the Mozilla mission unless we have a presence in these other spaces.

"Our stakeholders - we don't have shareholders - are not looking for a financial return on investment. The return on their time and energy and goodwill that they're looking for is the product that they like, and an internet that has a layer of user sovereignty in it.

Project Pancake may be Mozilla's next big earner

"Things like Pancake are really early. When we have an idea of 'wow this is really exciting', at that point you then say: 'Ok, we know what people love about it now - what are some sustainability ideas that we can try?'"

As for where those money-making models might emerge, Ms Baker is less forthcoming: "I don't have much to say on that one."

The BBC asked Google about how it sees the future of the Mozilla deal.

"Mozilla has been a valuable partner to Google over the years," says Alan Eustace, senior vice-president of search. "We look forward to continuing this great partnership in the years to come."

This bodes well. Indeed, to pull out of a company that exists in order to mobilise "openness, innovation and opportunity on the internet" might be squarely at odds with Google's mantra of "don't be evil". However, if Chrome continues to grow, that partnership may not be as lucrative as it has been to date.

But while users may be flocking in their droves to Chrome, they'd be wise to remember that some of the couldn't-imagine-a-world-without features of the modern browser are largely down to the volunteer minds behind the Mozilla project.

Equally important, argues open web campaigner and co-editor of BoingBoing.net Cory Doctorow, is Mozilla's place as a leading non-profit in the connected web.

"They can remain a kind of Switzerland of technology that really only has one raison d'etre, and that is to make the internet better," he told the BBC.

"When you look at the early days of Mozilla, it was all about acting as an honest broker for users.

"That remains the role that Mozilla has to play because they are an independent third-party that doesn't have a commercial dog in the fight."

- Published8 March 2012

- Published9 September 2011