ZX Spectrum's chief designers reunited 30 years on

- Published

- comments

More than five million copies of the various ZX Spectrum computers were sold over the family's eight year lifespan, not including third-party clones.

<link> <caption>Click here to see how the computer's design evolved</caption> <url href="http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/technology-17793214" platform="highweb"/> </link>

<bold>The ZX Spectrum is 30 years old. The successor to Sir Clive Sinclair's ZX81 - at the time the world's best selling consumer computer - it introduced colour "high resolution" graphics and sound.</bold>

<bold>It also offered an extended version of Sinclair Basic, a computer language with which hundreds of thousands of users were already familiar.</bold>

The thin Bauhaus-inspired design was sleeker than anything else on the market, but what was more impressive was its price: £125 for the basic model with 16 kilobytes of RAM, or £175 for the 48k model.

That allowed <link> <caption>adverts at the time</caption> <url href="http://zxplanet.emuunlim.com/zx-unleashed.htm" platform="highweb"/> </link> to boast: "Less than half the price of its nearest competitor- and more powerful".

Sir Clive believed hitting the low price points was crucial.

Rival Acorn Computers had beaten him to a contract to build a tie-in computer for an educational BBC television series which started in January 1982.

It seemed the best way to overcome that promotional advantage was to undercut the BBC Micro's £299/£399 charge - and the strategy worked.

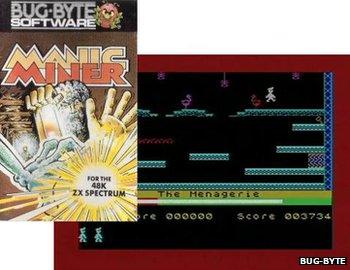

Titles such as Manic Miner, Jet Set Willy and Head over Heels helped drive the Spectrum's appeal

It also protected the Spectrum from the higher-specced, but more expensive, Commodore 64 which was unable to dislodge Sir Clive's computers from being the UK's number one selling computer.

Although some bad business decisions forced the sale of Sinclair Research's computer business to Lord Alan Sugar's Amstrad in 1986, the Spectrum remains a 1980s icon.

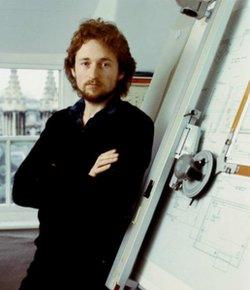

Sir Clive was the face of the company, but credit is also due to the original ZX Spectrum's engineer, Richard Altwasser, and its industrial designer Rick Dickinson.

The BBC reunited the two men about 25 years after they last spoke to discuss their work's legacy:

<bold>How much of an effect did hitting Sir Clive's price target have on the design? </bold>

<bold>Dickinson:</bold> Cost has always been very high on the agenda with all Sinclair products no matter how far back you go and Clive knew exactly where a product had to be priced.

Literally every penny was driven out where possible. So one of the consequences was that we would very rarely take an existing technology and simply mimic or buy it, but instead would engineer another way of doing it.

So for example with the Spectrum keyboard we minimised it from several hundred components in a conventional moving keyboard to maybe four or five moving parts using a new technology.

<bold>Altwasser: </bold>On the electronics side we needed to keep the silicon real estate as small as possible and continued to use the very cost effective Z80 processor. Much of that was achieved by having a very good BASIC interpreter design that could be kept in very little ROM memory space.

Rick Dickinson's drawing board - used to design the Spectrum - is now in London's Science Museum

<bold>Demand was phenomenal - within three months there was a 30,000-strong backlog of orders despite it initially being restricted to mail order. Was the scale of its popularity a surprise?</bold>

<bold>Dickinson:</bold> No matter how much history one might have with successful products like the ZX80 and 81 there is always a niggling doubt in one's mind that to come out with something new and significantly different is a risk. I think that we were all overwhelmed by the demand and the number of products that were sold.

<bold>Altwasser:</bold> I think with hindsight the BBC did an awful lot to popularise the use of micro-computers, and if we consider the fact the Spectrum was selling for half the price of the BBC Micro we shouldn't be surprised it was very successful.

I clearly recall having discussions that a time would come when every home would have a computer. We could see the applications and uses for everyday purposes.

We'd have these discussions with friends and family and people outside the computer club in Cambridge and people would scoff and say: 'Why on earth would a family want a computer in the home?' The success was I think beyond anyone's expectation. But perhaps with hindsight it wasn't totally unpredictable.

<bold>The success was also driven by videogame sales - the machines were originally marketed as an educational tool but you ensured titles were ready at launch.</bold>

<bold>Altwasser:</bold> Whilst as engineers we were hoping that people would turn on the computer and find out within a few minutes they could write a simple program and become programmers, clearly a lot of people wanted to use the computer for playing games.

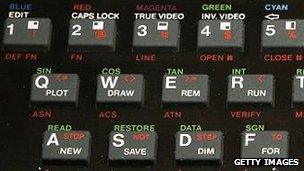

Different key combinations were needed to write each Basic command

By providing them with computer programs that they could either read from a little book and type in or load from a cassette, I think that we bridged the gap between those that wanted to learn a little bit about programming - perhaps starting with someone else's programs and making modifications - and those that wanted to primarily just have a usable game.

<bold>Dickinson:</bold> In the earlier days there was a mild disappointment that we were launching computers and not games machines but I think the games market eventually turned our machines into games products.

Once the company accepted that, Sir Clive realised that it was the clear route to one's bread and butter. There were a lot of companies set up writing games for the Spectrum and we also approached companies and writers specifically to make our own in-house games.

<bold>Not all the feedback was positive. Some described the keys of the original models of feeling like dead flesh.</bold>

<bold>Dickinson:</bold> I love reactions like dead flesh - you could certainly relate it to that. People seem to forget what they've paid for an instrument or a product. At the time there was probably no other way around it to meet the cost targets.

Even if some sort of miracle we had theoretically designed a better product I don't suppose for a moment it would have been any more successful and that we would have sold any more. I don't think there was anything I would change or have since regretted.

Mr Altwasser left Sinclair in 1982 and subsequently launched the short-lived Jupiter Ace computer

<bold>Another point of contention was that when you wrote code in BASIC you had to find the right key combination to trigger a command rather than letting the user type in the instruction letter by letter. That was changed in later models.</bold>

<bold>Altwasser:</bold> This was a concept that had been pioneered by Sir Clive in earlier models and had proved to be very successful. I think what it achieved with the Spectrum was the ability for a beginner to enter programs much more quickly than if they had to type in all of the individual letters.

In hindsight maybe the disadvantage of this was that we did add a lot of different keyword functions to different keys, so using the less frequently used keywords was a little bit complex.

<bold>Talk of computers today and many people think of games consoles or PCs that run ready-made applications. Even in UK classrooms programming fell out of fashion. That appears to be changing - but how much was lost?</bold>

<bold>Altwasser:</bold> I'm an engineer so I'm delighted at the thought that people are going to be encouraged through the availability of the Raspberry Pi to learn to do programming. If I look at the capability of that machine - the graphics pixel rate is 140 times greater, the processor speed is 200 times greater, there's thousands of times more memory.

So you would think the speed and power of that device compared with the ZX Spectrum gives it every possible advantage. But my impression is that the attention span of young people over the last 30 years has probably not lengthened.

What is important is not the technical speed of the device but the speed with which a user can get their computer out of a box and type in their first program.

Clive Sinclair sold his computer range and brand name to Alan Sugar's Amstrad for £5m in 1986

<bold>Dickinson:</bold> I concur totally with what Richard has just said. Although many Spectrum were sold for games, there were a lot of people who really gripped what all this was about - and what Clive was interested in in the first place - learning about programming and what you can do with programs.

Clearly we've spawned a generation which is now quite mature and has produced software for the many products that surround us.

<bold>Sir Clive sold out to Amstrad in 1986 and after a couple of revisions - involving the addition of a built-in cassette player and then a disc drive - production ceased in 1990. There are still some people who continue to code for it using emulators on PCs. But why do you think it ultimately failed?</bold>

<bold>Altwasser:</bold> I think I'd question the premise that the Sinclair model failed. Having a product lifetime of nearly 10 years and selling 5 million units - which I think is more than three times the volume sold for the BBC Micro - I don't think you can characterise that as failing.

I've been working in the computer industry recruiting software developers for more than a decade, and I'm continually meeting people who cut their teeth on a ZX Spectrum.

Part of that legacy is that we now have a generation of computer programmers who first got hooked by opening a box, looking at a screen and within a minute saying 'hey I've done something', within five minutes they'd written their first program and then they were spending every evening and weekend programming. I think the legacy of that is to be seen in the software engineering population of this country.

Later models of the ZX Spectrum did away with the original's rubber keys

<bold>Dickinson: </bold>I am rather sad that there isn't son of Spectrum around and the death of that was purely down to commercial aspects and the sale of the business to Amstrad which is well documented.

Sinclair products were born out of staggering innovation and clever shortcuts to get things into ever smaller packages at lower costs. Companies like Amstrad - which I have also worked for on a freelance basis - were more about taking existing technologies and finding special ways to stitch them together.

The Sinclair approach was far riskier as it was going out there and pretty well creating new markets. There was a purity in way the Sinclair products operated - raw access with pure simple code. And I think a lot of current day enthusiasts find that quite exciting compared to today's offerings.

<italic>Sir Clive declined to take part in the conversation.</italic>

- Published1 December 2011

- Published11 March 2011