The world's five biggest cyber threats

- Published

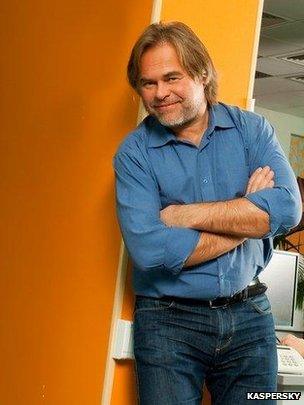

Cyber criminals are not stopping at infecting just a few computers - the threat is much bigger, says Eugene Kaspersky

Viruses are known to bring trouble - whether they make you sick or mess up your computer.

But these past few years, computer viruses have become much more elaborate. Criminals do not stop at stealing someone's personal data.

The cyber menace showed its true potential when the Stuxnet virus targeted Iranian infrastructure in 2010, in an apparent bid to disrupt the country's uranium enrichment programme.

As computers organise and dominate more and more of our world, five distinct threats are emerging, says Eugene Kaspersky, founder and chief executive of Russian computer security firm Kaspersky Lab and speaker at this year's Counter Terror Expo in London.

Complete darkness

The first threat is cyber warfare, he says - exactly what Stuxnet was about. And just last weekend, Iran took key oil facilities offline after their computer systems suffered a malware attack.

Eugene Kaspersky says he is seriously worried about the future of our world

This could one day happen on a much bigger scale, warns Mr Kaspersky. For example, entire nations could be plunged into darkness if cyber-criminals decided to target power plants.

"And there is nothing - nothing - anyone could do about it," he says.

"It is possible that a computer worm doesn't find its exact victim - and since many power plants are designed in a similar way [and often use the same systems], all of them could be attacked, around the world," he says.

"If it happens, we would be taken 200 years back, to the pre-electricity era."

International collaboration and treaties about the use of cyber weapons, similar to nuclear and biological arms control treaties, could help prevent such attacks. Many governments are acknowledging that there is a real threat.

Leon Panetta, the US secretary of defense, said this January that "the reality is that there is the cyber capability to basically bring down our power grid... to paralyse our financial system in this country to virtually paralyse our country."

At the same time, says Mr Kaspersky, huge amounts of money are being poured into the development of cyber weapons.

Last December, US Congress approved plans for the military to use offensive cyberspace methods if deemed necessary.

Mass conscience

The second cyber threat is the use of social networks to manipulate the masses, says Mr Kaspersky.

"During the Second World War, airplanes were used to drop propaganda leaflets over enemy territory - and the same is already happening with social networks," he explains.

For instance, last month rumours of a possible coup flooded China's blogosphere - with some reporting tanks and gunshots on the streets of Beijing.

"There weren't any tanks, it was all a lie," says Mr Kaspersky, who happened to be in China at the time.

"But if such information is put out by someone of high authority and somewhere where millions can read it, it may create a panic."

Social networks played a key role in coordinating the protests during last year's Arab Spring.

Mr Kaspersky argues that some organisers of the uprisings may have been based outside those countries, using the web to manipulate the masses.

Web kids

The gap is widening between children growing up in today's digital world and their parents

The third threat is how the internet generation will engage with politics, he says.

Today's children are growing up in a digital world, but at some point they will become adults - and will have to vote.

"And if there's no online voting system, these kids won't physically go anywhere to vote, they just won't, they'll refuse," says Mr Kaspersky.

"The whole democratic system could collapse then - the gap between parents and children will get much wider, it will become political, with solely the parents being involved in politics.

"So the lack of well-established online voting systems is a real threat to democratic nations of the Western world."

Hacking attacks

Cyber crime has been a real concern of any computer user for years. Recently the threat has spread to smartphones.

No computer is safe from viruses. Every day, cyber criminals are infecting thousands of machines around the world.

Although many believe that Apple Macs are immune to infection, just this month more than 600,000 Apple computers were infected with the so-called Flashback Trojan.

And hacking mobile phones has become a real business in Russia, Asia, and other places where pre-paid phones are common.

"We estimate that criminals who target mobile phones earn from $1,000 to $5,000 per day per person," says Mr Kaspersky.

"They infect mobile phones with an SMS-Trojan virus that sends short texts to a number that is not a free number, until the victim's account is emptied.

"An average person won't have too much money on a phone account, but when hundreds of thousands of phones get infected, it is a lot of money.

"It's like this joke we have in Russia: 'Why are you robbing this granny, she's only got a rouble? And the thief answers: Well, 10 grannies - it's already 10 roubles'."

And the threat is dramatically escalating. In December 2011 alone, Kaspersky Lab discovered more than 1,000 new Trojans targeting smartphones. That's more than all the smartphone viruses spotted during the whole eight years before.

Mobile phone hacking is also getting more attractive with the rise of the Near-Field Communication technology (NFC), which turns mobile phones into wallets or helps people to read product information.

"To avoid their phone being hacked, people should install a security system on their phone," says Mr Kaspersky, and the technology should be better regulated.

No privacy

Cyber warfare could be the biggest cyber threat facing the world

Finally, there is the problem that our privacy disappears, says Mr Kaspersky.

"Nowadays, privacy has become non-existent - there's Google street view, drones that silently fly overhead and take photos, CCTV cameras everywhere," he says.

"And of course, there are all these companies on the web that ask you for a lot of personal data - and often, much of it is unnecessary."

He calls on governments to regulate how much information companies are allowed to demand.

"In the end of the day, it's not only dangerous for you personally, but your entire nation could become hostage," he warns.

"If a criminal gets hold of personal information about one million UK citizens, could it be used against the UK? Yes, it could be.

"And that's when it gets very scary."

- Published13 April 2012

- Published5 April 2012

- Published16 March 2012