Ubuntu's Mark Shuttleworth on shaking up system software

- Published

Ubuntu says it aims to offer users both a stylish interface and the benefits of being part of the open-source community

Free of charge, free of viruses and designed to outpace its rivals on low-end systems - Ubuntu has some obvious advantages.

The operating system claims 20 million people use it a day. Not an insignificant number, but still a drop in the ocean compared to Microsoft's Windows or Apple's OS X.

Even so, lead designer and one-time astronaut Mark Shuttleworth hopes that last week's major upgrade to the Linux-based project will produce an outsized splash and increase the size of its somewhat divergent customer-base.

"In terms of our user, they would split into two sorts of camps," he says.

"One, not very tech savvy, that has an old PC lying around and Windows is getting difficult because of the computer's age or viruses, and Ubuntu gives them a nice basic all-purpose PC with a great web experience.

"The other group tends to be the next generation of tech entrepreneurs - people who are passionate about technology and want to do amazing things with it."

Mr Shuttleworth paid Russia $20m (£12.3m) to become the first African in Space

Mr Shuttleworth counts Wikipedia and Facebook's Instagram photo app among his clients.

A third class of users is also attracted to the system - public bodies looking to cut their IT bills. The Dutch ministry of defence, part of France's police force and schools across the south of Spain have all opted to switch thousands of their PCs to the software.

Type to control

Ubuntu is able to offer itself as a free download thanks to coders across the world volunteering to develop the open-source project.

Mr Shuttleworth's London-based company, Canonical, manages and funds the endeavour and makes money back by offering support, training and online storage.

The system may remain niche so long as it lacks native versions of big name software like Photoshop, iTunes and Microsoft Office - despite alternative products - but it may still shake up the wider industry thanks to efforts to incorporate innovative technologies.

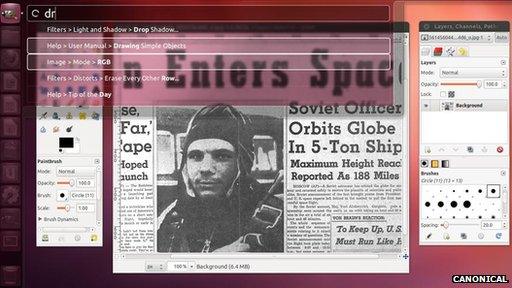

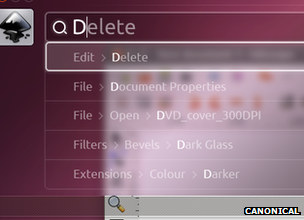

The adoption of a head-up display (HUD) in the upgrade is a case in point.

It aims to replace increasingly overloaded point-and-click menu systems with a panel into which users type what they want the computer to do. The computer then tries to offer up a list of functions that match their request.

"The core idea is that instead of hunting for some functionality in a menu you can simply express what you want," Mr Shuttleworth says.

"You can say I want to send that to grandma, or I want to back this up.

The HUD tries to predict which function or file the user wants as they type it in

"It's driven by the idea that search or expressing your intent has become really powerful. If Google can turn the whole internet into one page of likely results just based on the one sentence you give it, why can't we do that with your email or graphics application?"

Natural interfaces

For now the innovation remains optional. The software designer admits it still needs "a great deal of work", but he adds that it is only one of many steps he hopes to take towards a more intuitive, multi-sensory experience.

"You could imagine having the device track your eyeballs so it knows what you are looking at - so you could look at a movie and say 'I want to watch that.'

"You can get away from the designer of the application having to provide a cumbersome way to express all the things you can do which you have to navigate, and just let you just say what you want to get done - whether that's by talking, pointing or by touch interface - all of these things have to come together to make it feel more human."

Delivering these ambitions will take years, perhaps decades.

In the shorter term, Ubuntu's fans have been excited by a job posting which discussed creating a Ubuntu smartphone system.

Mr Shuttleworth refuses to reveal any details, beyond hinting that it will be a closer relation to the firm's core product than some of its rivals' mobile systems are to their desktop equivalents.

"You know you wouldn't want to run Mac OS X nor Windows 8 on a phone," he says.

"Those companies have quite different sorts of interfaces. We think we have found a way to have a more harmonious portfolio... we will be judged on what we ship."

Pocket-sized PC

The firm's smartphone efforts are also concentrated on "Ubuntu for Android" - an app that makes high-end phones act like a PC when docked with a monitor and keyboard, which is due out later this year.

The firm suggests businesses could ultimately cut costs by only having to buy a single device for each of their employees.

It is a radical proposition, and also a bit of a philosophical challenge.

"There are two counter-balancing forces - one force saying everyone should have fewer CPUs [central processing units] as their phone can replace other devices," says Mr Shuttleworth.

"But then you have exactly the opposite trend which is saying that anything that could have a screen can also have a brain, a memory and a personality - printers with touch-screens, desk phones that deliver your mail. And those are two completely contradictory forces.

Canonical says its desktop app should work on "late-2012 high-end Android phones"

"Holding those two opposing ideas in our head at the same time is what's really exciting."

Patent problem

Other ambitions include the roll-out of the first Ubuntu powered television sets and perhaps support for mark two of the Raspberry Pi stripped-back computer, whenever it launches.

"We just couldn't connect all the dots in the first version... I'd be delighted if a future version worked with us," Mr Shuttleworth adds.

But as his firm rushes to release new innovations, one major cloud looms: the threat of a patent dispute.

Although Canonical has avoided becoming involved in one of the rising number of lawsuits sucking up time and brainpower at its competitors, it is an ever-present concern.

"We know that we are sort of dancing naked through a minefield and there are much bigger institutions driving tanks through," Mr Shuttleworth says.

"It's basically impossible to ship any kind of working software without potentially trampling on some patent somewhere in the world, and it's completely impossible to do anything to prevent that.

"The patents system is being used to slow down a lot of healthy competition and that's a real problem. I think that the countries that have essentially figured that out and put hard limits on what you can patent will in fact do better."

- Published8 March 2012

- Published8 March 2012