Viewpoint: The Cambridge Phenomenon, five decades of success

- Published

About 5,000 hi-tech firms have been founded in and around Cambridge since 1960

Over the past half a century, the group of technology and bioscience-based companies in and around Cambridge has become one of Europe's most successful and best known clusters of its kind.

Some like the chip designer Arm Holdings are still independent - others like the software firm Autonomy have been the target of multi-billion pound takeovers.

Since 1960, about 5,000 hi-tech companies have been founded in the area, of which 1,400 remain in business, employing about 40,000 people.

A new book "The Cambridge Phenomenon" is published this week, tracking and seeking to explain the area's success.

Its title picks up on term coined by the Financial Times in 1980 when the newspaper reported that the technology being produced would be "vital to Britain's basic prosperity and to the continuing ability to contribute on an international level".

To coincide with the event, the BBC invited the book's authors to describe what lessons could be learned from Cambridge's success.

Medieval start-up

Technology clusters are big news. The recent launch of the Google Campus at London's Silicon Roundabout shows how much importance international companies and governments place on centres of creativity and innovation as engines for driving future profits and prosperity.

Horace Darwin, son of Charles, founded the Cambridge Scientific Instrument company in 1881

But while Silicon Roundabout is brand new, Cambridge has been home to high technology companies for centuries.

The first high-tech company in Cambridge was the University Press, founded in 1534 by Henry VIII, and the oldest publishing house in the world.

Things were quiet for a while, but a few hundred years later, Charles Darwin's son, Horace, founded the Cambridge Scientific Instrument company, and the rest, as they say, is history.

Today, Cambridge is home to - among many others - Frontier Developments and Jagex Games Studio, two of the biggest computer games companies in the UK; Abcam, the "Amazon of antibodies"; and Arm Holdings, a company that designs the chips found in more than 95% of the smartphones in the world.

Test tube patients

The 1960s and early 1970s were tough for technology companies in Cambridge, with attitudes and planning restrictions set against anything vaguely commercial.

A local planning officer, after he had promised faithfully not to close it down for contravening any number of regulations, was taken to visit a computer software company tucked away in a side street in the heart of Cambridge.

He was shocked to find a normal terraced house "packed with mini-computers and chaps with beards designing stealth submarine systems for the US Navy".

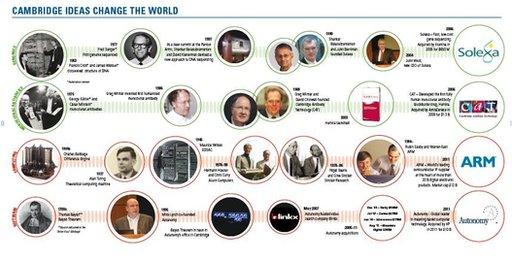

A primary source of innovation is, of course, ideas, and Cambridge ideas have been changing the world for centuries, from Isaac Newton and his apple to the genomics company Horizon Discovery and its X-Man cell lines - the "patient in a test tube" designed to allow scientists to work out different people's response to cancer drugs.

Perpetual Motion

Entrepreneurs explain the allure of Cambridge for tech

Cambridge has produced 11 tech companies worth over $1bn (£620m).

But equally important is the diversity of smaller companies employing highly skilled individuals and the increasing number of international firms choosing to locate research and development labs here.

This continually evolving community is like a perpetual motion engine, attracting fresh, bright people inspired to do things differently. This creates not just embryonic companies but entirely new industry sectors.

Cultural changes have been a vital ingredient in the community's success and there are, we believe, three key factors.

Dual roles

The first was a cultural shift in views about "commerce" when the University of Cambridge allowed academics to pursue non-academic roles.

We can now see the success of this policy with serial entrepreneurs such as Greg Winter of Cambridge Antibody Technology, Shankar Balasubramanian of Solexa, and Andy Hopper of Acorn Computers and Virata - who are also professors - inspiring the next generation of students.

Secondly, we needed to overcome the inherent British fear of failure.

Runescape holds the Guinness record as "the most popular free-to-play massively multiplayer online game"

Setting up a business, particularly one based on a novel technology, is inherently risky.

We have now developed a better understanding of the nature of failure and distinguish between external events, such as loss of funding after the bursting of the dot.com bubble, and internal factors such as poor decisions, which can be learned from, and this has increased confidence.

Soft-starts, where technology is developed within a company before being spun-out, has also successfully de-risked technology for many investors.

Money and nurture

The third factor is the "Cambridge Spirit".

People in the Cambridge cluster are willing to collaborate and share knowledge. They are also willing to put something back, and this is particularly evident in the growth of angel funding groups, where successful local entrepreneurs offer experience and finance, providing a nurturing environment for young companies.

In fact, the Cambridge Angels, a group founded ten years ago, now has so many members it has had to set up a second group.

Cambridge keeps evolving. Having 800 years of history and 88 Nobel Prize winners affiliated to the University of Cambridge since 1904 is obviously an advantage, but in some industries it is the "personal brand" offered by an entrepreneur or scientist that is important.

The seminal computer game, Elite, was co-created by David Braben, founder of Frontier

Highly original and successful people attract attention, and investment.

Increasingly we are seeing companies staying in Cambridge after acquisition by overseas players such as Broadcom, HP, Medimmune and Takeda, while others, like Amgen, Microsoft and Toshiba, have chosen to locate and maintain research labs and development teams here to be close to these people.

Spin-in, where companies choose to locate here, is part of the contribution Cambridge technology continues to make to the economy.

We don't measure success simply by the size of the companies we create.

Cambridge's strength is a continually evolving ecosystem employing many thousands of people. It is inspiring new markets, new companies, new products and services, and is sustainable.

Charles Cotton is founder and chairman of The Cambridge Phenomenon, the organisation behind the book. His directorships include semiconductor company XMOS and Cambridge Enterprise, the organisation within the University of Cambridge responsible for spin-outs and licensing activities. He was previously sales and marketing Director at Sinclair Research.

Kate Kirk is a freelance editor specialising in work for think tanks and business schools.

The authors have created a chart highlighting some of the key names and tech companies in Cambridge over the past 50 years

- Published9 May 2012

- Published28 February 2012

- Published8 March 2012