Connected sky: Surfing the web above the clouds

- Published

Onboard internet has been a reality for a while, but not many passengers use it

As his plane prepares for take-off at London's Heathrow airport, frequent flyer Matt Hatton knows that in just a few minutes his smartphone will become dead weight.

Well, almost.

No email checking. No Facebook status updates. No YouTube, Spotify, Google search.

In short - no internet.

Despite a number of airlines now offering in-flight internet, also called onboard wi-fi, far from every plane is equipped with the necessary technology.

And even if the connectivity option is there, not many passengers use it.

It is rare for the service to be free of charge - often, the costs are sky-high, compared with terrestrial prices.

And for many flyers, the experience can be different from what they are used to at home or in the office.

"It certainly isn't the same as high-speed broadband on the ground; it's very slow," says Mr Hatton, director at UK-based telecoms consulting firm Machina Research.

"Anyone hoping to use it for web browsing as they would at home would be rather disappointed.

"My experience was on Norwegian and it was free. And it would have to be! I probably wouldn't have paid for it."

Mr Hatton says that he mostly used the service for work-related email, but after hitting "send", the letter would "sit in my outbox for a very long time and eventually send".

Rise, fall, rise

For some people, it has become vital to stay connected all the time and everywhere - even above the clouds

But it may all change, and soon, say analysts.

The recent deal between the British satellite telecommunications company Inmarsat and one of the biggest global aviation suppliers, US-based Honeywell, may help give in-flight connectivity a boost.

Inmarsat plans to launch three satellites into orbit in the years to come, with the first one planned for 2013.

The firm says the project, called Global Xpress, will provide global coverage and essentially make in-flight wi-fi fast, cheap, reliable - and available anywhere, even on long-haul flights.

But in-flight wi-fi isn't new.

In fact, it is a decade old - and has already enjoyed one rapid rise, followed by a quick tumble in the mid-2000s.

The first planes with airborne internet appeared back in 2003, after Boeing's ambitious initiative to combine its knowledge of satellites and expertise in plane manufacturing.

Dubbed Connexion by Boeing, the venture allowed air travellers to stay connected with the help of high-speed signals from geostationary satellites and special receivers fitted on the aircraft.

But after a steep rise in interest, with airlines queuing to get the service and signing deals just months before 9/11, it all went downhill as the airline industry slumped in the wake of the terror attacks.

Without enough airline partners and not too many passengers interested in paying for the service in those early days of mobile internet, the project came to an end in 2006.

But slowly, over the past few years, airborne wi-fi has become more popular once again.

More and more firms now aim to satisfy the public's urge, driven by the explosion in mobile devices, to always stay online - even above the clouds.

But there is little doubt that in the near future, browsing at 36,000ft will become a similar experience to surfing the web in your own bedroom - if you happen to have high-speed internet there, that is, says Diogenis Papiomytis from consulting firm Frost & Sullivan.

"Global Xpress will certainly make broadband on planes faster, but not necessarily cheaper," he says.

"The promised speeds are 50Mbps (megabits per second) for downloading content during flight and 5Mbps for uploading content - faster than the average UK household speed of 6.7Mbps."

It is not sure that those will indeed be the speeds, he adds, and about 10Mbps would probably be a more realistic goal, closer to what is currently available in many households.

The speed of 10Mbps would also be 10-20 times faster than what airlines offer on planes today.

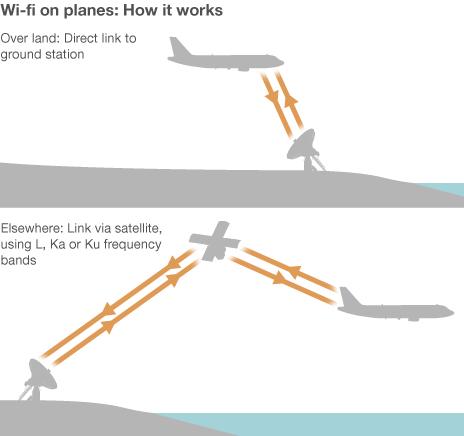

There are different ways to let users go online in the sky.

Connexion by Boeing showed that in-flight connectivity via satellite was possible - at a cost.

After it was shut down, other companies explored alternatives.

Air-to-ground

US firm Gogo turned to the Aircraft to Ground (ATG) solution, which uses existing mobile phone base stations, without a need for a satellite.

Right now, it is the most popular in-flight wi-fi service provider in the world, equipping more than 85% of all North American aeroplanes.

But the coverage is limited to aircraft flying over land, and - at the moment - it still has to work hard to win over passengers. According to In-stat, a US research and consulting firm, currently only about 8% of air travellers in the United States pay for onboard wi-fi.

Gogo's prices range from $4.95 (£3.07) if a flight is a maximum of 90 minutes long to $9.95 (£6.18) if you are in the air for up to three hours.

Not everyone uses the service simply because some people are still taken by surprise that it is actually offered, while others prefer to disconnect, sleep or relax, being "more concerned with the nuts and white wine", says Ian Smith from UK firm Butterfly, who travels regularly around the US.

But he tried it out - and was satisfied, he says.

"In my experience, the connection was very fast with low latency - lots of image-based web pages were loading immediately without major delays.

"I did not attempt to upload any great amount of data other than standard twitter conversations and emails.

"With the current service, I thought it was good value with good performance - however, as adoption and awareness increases, with more people all accessing the internet, I would think it would grind to a halt."

Indeed, when Google decided to sponsor some Gogo-enabled flights last year, letting passengers access the internet free, usage rates skyrocketed and speeds became extremely slow.

Inmarsat plans to launch three Ka-band satellites in the next few years

ATG may be a solution over land, but passengers on long-haul flights across oceans will need a satellite if they are to stay connected.

Satellite is the only way to deal with this problem, says Mr Papiomytis - and this is what prompted providers like Viasat, Inmarsat, Panasonic, OnAir and Row44 to explore the satellite option all over again.

Boeing's Connexion used the Ku- and L-band frequencies, external. But these bands do not provide for the fastest data rates, which is something Inmarsat aims to change with Global Xpress.

"We're flying three satellites, with the first one going up next year, that will provide global coverage in a frequency band called Ka, external," says Leo Mondale of Inmarsat.

"These higher frequencies will enable real broadband communications to and from an aeroplane, higher speeds and cheaper prices that we think will fit with the expectations of the market."

Inmarsat's partner in the deal, Honeywell, will be developing the onboard hardware for the Global Xpress network, such as the antennas to send and receive satellite signals.

"As passengers get used to being connected at 35,000ft, they are not only expecting connectivity, but good connectivity that allows for a multitude of internet-enabled applications," says Carl Esposito of Honeywell.

"Aircraft access is becoming easier with wi-fi roaming services, automatic GSM authentication and simpler billing options," he says.

"These will make connecting on the airplane as easy as at Starbucks."

Some people still regard long flights as an opportunity to relax

- Published20 October 2011

- Published8 June 2010