A farewell to ARM: Tudor Brown leaves the chip designer

- Published

Tudor Brown says at the age of 53 he thought it was "time to move aside for some younger people"

When Tudor Brown stepped down as president of ARM Holdings earlier this month, he left behind one of Britain's and indeed the world's, most successful technology companies.

The designs it produces have been licensed and used to build processors at the heart of many of today's bestselling gadgets.

Samsung's Galaxy phones and tablets, Amazon's Kindle e-readers, Nintendo's 3DS hand-held games consoles and Canon's cameras are just some some of the products to use its chip architecture.

October's release of an ARM-compatible Windows system and new super-low powered microprocessors point to further growth.

But looking back, Mr Brown is first to admit that his time at ARM was not all rosy.

"All of ARM's early products failed commercially," he tells the BBC.

"There's a long list of them: the Acorn machine, the Apple Newton, the 3DO multi-player - the world's first CD-based games console - there were a whole bunch of things like that."

From Archimedes to Apple

Mr Brown's involvement with ARM predates its existence to 1983 when he was employed as an engineer at Acorn Computers. The firm was riding high off the launch of the BBC Micro and had asked him to help evaluate processors from Intel and Motorola for follow-up products.

He recommended it develop its own RISC-based processors - what were to become the first ARM (Acorn RISC Machines) chips.

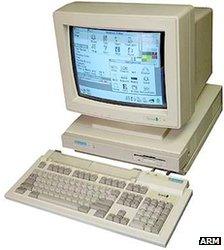

But the project was hamstrung by the fact it took four years to develop the computer that ran them, the Acorn Archimedes.

The Acorn Archimedes featuring the ARM2 chip launched in June 1987

"By that time Acorn wasn't able to aim at industry because the PC was getting a foothold, so it was forced into the education market again," Mr Brown says.

"It just wasn't big enough to sustain Acorn as a company, which is why it kept on going bust."

Mr Brown says it was around this time Apple first started showing interest in the ARM technology. The US firm initially rejected it because it viewed Acorn as a competitor.

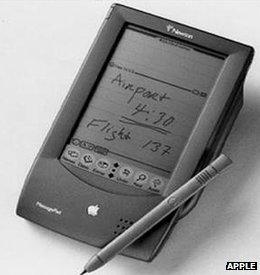

But after an aborted effort to use a product from the telecoms firm AT&T, it returned in 1990 seeking help to build the Newton, the world's first PDA (personal digital assistant).

The two companies agreed to create a joint venture - ARM Holdings - but once again success proved elusive.

"Newton launched in 1992 and it was another commercial flop," says Mr Brown.

"It was way ahead of its time, it was too big, it was too slow, its handwriting technology didn't work. The sort of vision of what it was supposed to be was remarkably close to what the iPhone is today... but the technology wasn't fast enough for the time."

Rise of the mobile

Mr Brown notes that the device may have failed, but the cash Apple later made from selling its shares in the firm proved useful.

"[It] sort of rescued Apple financially, and a few years later Apple started using ARM technology in the iPod, and eventually that same technology got transferred into the iPhone and iPad."

ARM itself was also shaped by the failed project in ways that would serve it well later: a focus on low-power usage which forced it engineers to aim for a "simplicity and elegance" of design.

Its fortunes turned when designs based on those principles were used by Texas Instruments to build chips powering Nokia's GSM phones.

Their popularity helped propel ARM to a successful stock market flotation in 1998, linking its fortunes to those of the mobile industry. But it always had wider ambitions.

"If you look at our marketing material right back to the IPO days we were saying that ARM technology is applicable to a wide range of products - TVs, disk drives and cars," says Mr Brown.

Internet of things

Those products may have accounted for a smaller proportion of ARM's business than expected, but the firm now believes that much of its future growth will come from microprocessors based on its new super-energy "Flycatcher" designs.

Apple helped create ARM Holdings to build a chip for its ill-fated Newton

These are targeted at connecting things like fridges, medical equipment and energy meters to the net.

"The internet of things will start to see appreciable volumes in about 2015," says Mr Brown.

"It's starting to get there because ARM technology is getting so small and so cheap at the bottom end of the scale.

"A few months ago we brought out our smallest ever product, the Cortex-M0+.

"I did a quick sum on the numbers being presented and it told me it could run at a reasonable speed for 20 years on a single AA battery. That enables a whole bunch of things that wouldn't otherwise be possible."

Avoiding factories

There is an obvious temptation for ARM to want to make such devices rather than rely on royalty and licence fees, but Mr Brown says it would be wise to resist.

"It's often discussed, but dismissed in the same vein fairly quickly," he says.

"I've always said it's not the technology that's driving this company forward, it's the business model that's put ARM where it is today.

"Yes, the profit margin we make out of every chip that is sold is tiny, but our business model allows our partners to ship an awful lot of chips."

He adds that he thinks Britain's days as a "strong" manufacturer are behind it, but admits the picture becomes more complicated when it comes to trying to map ARM's success to the wider economy.

"There is manufacturing in this country, but the psyche of the British people with its chaos and flair means we are quite good at inventing things but not so good at doing things repetitively," he says.

"If I look at wealth creation, then the UK should be doing the kind of things we're doing - the high-end high-value stuff.

"But if I look at employment, it's a rather more difficult story, because obviously a company as successful as ARM only employs about 1,000 people in this country."

'Patent bubble'

As a business that does not physically produce any goods, ARM relies on its intellectual property rights. But Mr Brown sounds dismayed by the rising number of patent lawsuits and portfolio sales.

"There's no question right now we are living through a patent bubble and the valuations that are being paid for these patent portfolios don't really bear sense," he says.

"It doesn't seem sort of fair and it's hurting people.

"ARM has spent hundreds of millions of dollars developing technology, and we should be able to protect it... so in that sense patents are essential and sometimes you have to fight in court.

ARM only charges a 13-20p fee for each microcontroller based on its Flycatcher design, but believes billions may be built

"But that's quite different from some of the perceived values of these portfolios being sold around."

Some analysts have suggested that ARM's rich patent portfolio could make ultimately make it a takeover target.

After Hewlett Packard's acquisition of another UK tech giant, software firm Autonomy, last year there has been speculation that the chip designer could be bought by one of its clients.

But as he walks away from the firm, Mr Brown says he is hopeful it will remain independent.

"ARM is a completely unusual company, it relies on being at the hub of this complex ecosystem that we've built," he says.

"We'll happily license any company our technology for a few million dollars while it would cost them several billion dollars to buy us. We can't really see the industrial logic of why anyone would want to buy us.

"But you can never say never, some wild things can happen."

- Published26 April 2012

- Published13 March 2012

- Published10 November 2011