Makers bring sounds, lights and sights to Manchester

- Published

A mannequin turned into a life-size game of operation featured at the Mini Maker Faire

The younger generation of makers were much in evidence at the Mini Maker Faire held at Manchester's Museum of Science and Industry over the weekend.

The two-day show gave home hardware hackers, tinkerers and hobbyists a chance to show off some of the projects they have worked on in their spare time.

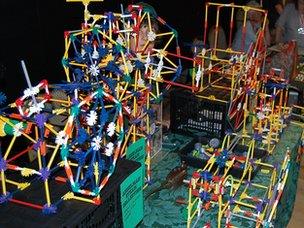

Ten-year-old Jake Addelman, the youngest UK maker at the Faire, filled his exhibit space with scale models of steam engines he built using parts from the popular K'Nex construction kit.

"They are all based on real engines," he told the BBC, adding that each was a copy of one of the many engines he had seen during trips to industrial heritage sites.

The working parts of each engine, despite being built out of the spindly rods in the K'Nex set, demonstrated the mechanical innovation key to that machine, the youngster added.

Some, such as James Watt's pioneering engine, were well known, he said, but others were more obscure.

One, known as the grasshopper engine for the distinctive movement of its crankshaft, was only built to get around the patent Watt had on his own design, he said.

"I understand how they all work so it's easy to make them," he said.

Another young maker who made home hackery look easy was 13-year-old Amy Mather, who took an Arduino-powered volcano to the Faire.

The Arduino micro-controller is a popular gadget for many makers because it simplifies the job of dictating what electronic components will do.

Ms Mather created the volcano, which uses LEDs and a small text display to explain what happens when one erupts, for a school geography project (for which she won a commendation).

The first version took two weeks to put together but Ms Mather has been tinkering with it ever since.

A late addition, on the night before the Faire, was a speaker so the volcano plays music as it cycles through its eruption sequence.

"Getting the sound to come on at the same time as the lights was the trickiest part," she said.

Ms Mather is not just skilled at using and programming the Arduino micro-controller. She has been using the Scratch click-and-drag programming tool to make games and is on familiar terms with HTML and Javascript.

"I'm also learning Python so I can use the Raspberry Pi I've just got," she said.

Man maker

Many of the other projects on show at the Faire were designed to catch the attention of children to fire an interest in electronics and home hacking.

"Games are a great way to engage people because everyone knows what they are," said Alex Lang of the Manchester hacking collective Hac:Man.

Hac:Man's success with a giant Etch-a-Sketch at a Maker Faire in 2011 got the group thinking about a follow-up, said Mr Lang.

"We decided we would pick a family game we could use to inspire kids and that they could have fun with," he said. "We chose Operation because its reasonably simple to implement."

Converting the shop dummy to a full-size version of the Operation game took about two months of work, said Mr Lang. It uses metal spaghetti tongs in place of the tweezers in the original and players can try to use them to remove the mannequin's brain, heart, gut or femur.

The most complex part of the build was etching the printed circuit boards that spotted when a body part or the tongs touched the live edges of the hole it was in, said Mr Lang.

A Raspberry Pi computer sat beneath the mannequin playing robotic screams when a body part was removed too roughly.

Jake Addelman showed off a formidable collection of scratch built steam engines

Maker Chris Ball brought along a more melodic sound-making machine in the shape of a framed laser harp.

Mr Ball, an accomplished musician, picked the harp as a beginner's project and managed to make the instrument out of spares and over the counter parts for less than £100.

As its name implies, the laser harp has beams of light rather than strings which are "plucked" and a note sounded when an object, such as a hand, blocks one of the beams.

"I've seen people make smaller versions in shoe boxes," he said, "but I wanted to make one that's actually musically useful."

Figuring out how to wire up the 14 laser diodes, sensors and accompanying electronics turned out to be a tricky project. Not least, he said, because he wanted it to detect the force with which people were "plucking" the beams of light and adjust the strength of a note accordingly.

"A laser beam has a width," said Mr Ball, "If you measure how long it takes to go on and off you can work out the force put into it."

Mr Ball is now working on a series of other instruments and eventually hopes to use them all in a musical maker band.

- Published7 June 2012

- Published19 July 2012

- Published5 July 2012

- Published22 September 2011