Viewpoint: Changing the curriculum won't be enough to get kids to code

- Published

Young Rewired State is an annual week-long event giving children the chance to learn coding skills from experts and each other

This year has seen increasingly noisy calls for revolution in Information Communications Technology (ICT) education, from Google's Eric Schmidt to Ian Livingstone - president of video game publisher Eidos - people have been stating the bleeding obvious: Our children need to learn how to build and design digital technologies, and not be passive users, passengers in the sidecar of a revolution that no one imagined would affect every aspect of people's lives.

Douglas Rushkoff makes the argument in the most cohesive fashion in his book: Program or be programmed, external.

"The real question is, do we direct technology, or do we let ourselves be directed by it and those who have mastered it?" he wrote.

"'Choose the former, and you gain access to the control panel of civilization. Choose the latter, and it could be the last real choice you get to make."

It's not hard to make the argument. What has been surprising is the assumption by parents and industry that children were being taught such skills in school - and the sickening feeling when it dawns on everyone that actually the curriculum has not been monumentally overhauled during the world's latest and greatest digital renaissance - indeed they were cocooned in a small world of denial.

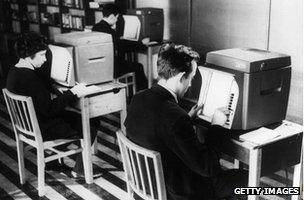

There have been big changes since early school computer classes in the 1960s

Wrong problem

Schools now are scrambling to address this, after the Secretary of State for Education Michael Gove spoke earlier this year, exhorting teachers to take up their computers and lead the kids forward to a world of knowledge, power and more importantly jobs.

But the problem is not that we can't get the right GCSE syllabus - although to their credit AQA (Assessment and Qualifications Alliance) have had a pretty awesome stab at it - nor is it that the teachers are not trained to teach this right now, nor is it even that those who have the computer science degrees and skills choose more lucrative careers than teaching.

No. It is that the way we learn is changing - dramatically. Education is metamorphing into a strange new being and no one knows what it is yet.

Fearing the web

How can closed analogue schools work in an open digital world?

Teachers struggle daily with kids distracted by social media and the sophisticated phones and technology they carry with them every day.

School's prescribe blanket bans on social media and try to police Facebook activity of their pupils.

Parents turn to schools to help punish and protect their kids from the digitally dangerous world, where predators and bullies prey on these innocent minds.

Khan Academy is one website offering free computer science lessons over the web

Their solution: Close access, restrict and deny. Scare-mongering is rife, warnings and hectoring videos ring out across the classrooms of the UK.

It is a world of fear because there is little understanding. This is not unusual during a time of immense change, but we are already losing this battle.

It is time for everyone to man up - to open up and to really look at what is happening.

Children will not learn how to live, work and cope in this digitally driven world without having a deep cultural understanding of how it works. And they will not have this deep cultural understanding by sitting in closed classrooms, measured by set targets, removed from digital society and banned from the open web.

My firm belief is that we need to open up our education system, give the children the elements of understanding and knowledge to navigate the online space.

Learning online

The Khan Academy is one example of how it could begin to work - children learning outside the classroom, with online resources and remote mentors.

How about subject teachers who are renowned experts? Who wouldn't like to be taught maths by Conrad Wolfram or story writing by JK Rowling?

Does it matter that the lesson was delivered by YouTube? The classroom becoming the place where pupils come to share and show what they have learned - a vibrant place with teachers there to curate the classroom. Peer-to-peer learning in true fashion.

From my own experience I can vouch for the fact that this method works.

I am a co-founder of an organisation called Young Rewired State (YRS). For the last four years we have found and fostered the children of the UK driven to teach themselves how to code.

We have provided them with a big annual event, where they flock together in centres around the UK and build something in a week, putting to use the skills they have taught themselves alone throughout the year.

They work together, creating the best possible digital tool they can think or, be it a website, a game, an app, a widget or the next big thing in social technology - even real life stuff.

Last year, we saw the first use of the Arduino, a programable microcontroller. I am expecting robotics and the Raspberry Pi to feature highly this year.

Children show off their programs to each other at the YRS event

At the end of the week, we bring them all together and they have a day where they showcase what they have built to each other, their friends and family, industry, press and judges (for fun and prizes).

Every year the kids that come back come back stronger and more excited.

The network is built around hyper-local friendships and collaborations, supported by a world-wide mentor/teacher network.

It sounds complicated, it is not. And it works, every year these kids get better, they push themselves to learn more and they teach more - many of them tutor their friends, write lessons, record educational videos... it works.

Not every child need to be a programmer, but every child need to be equipped with a fundamental understanding of the world they are growing into.

Knowledge banishes fear and being frightened of the digital revolution, whilst understandable is unnecessary. No single teacher or classroom could ever hope to grasp and teach this - it is all moving too fast.

Emma Mulqueeny is chief executive of Rewired State. Its Young Rewired event runs between 6 and 12 August.

- Published3 August 2012

- Published20 July 2012

- Published28 November 2011

- Published27 April 2012

- Published23 May 2012