Geek camp comes to Milton Keynes

- Published

Organiser Jonty Wareing offers the BBC a tour of the Electromagnetic Field Festival

At first glance, it looked like a typical summer festival was getting under way in Pineham Park, Milton Keynes - a haphazard collection of tents, distinctive portable toilets and a very well-stocked bar.

But not every festival has its own bespoke 300 megabits per second (Mbps) broadband connection, electricity almost literally on tap thanks to networks of specially adapted festival toilet cubicles called Datenklos and delegate badges that change colour according to who you are meeting.

The very first Electromagnetic Field Festival, known as EMF, started at Pineham Park in Milton Keynes on Friday and runs until 2 September.

Aimed at "people with an inquisitive mind or an interest in making things", events planned for the weekend include soldering and blacksmith workshops and the opportunity to learn how to build a mechanical Turing machine.

"People just want to show off things they've made - the whole camp is about sharing and teaching others," said organiser Jonty Wareing.

"There are hacker camps abroad but they are more focused on computers - there's more of a culture here for physical stuff."

Mr Wareing and his team actively encouraged all attendees to bring their own creations and cheerfully admitted he had "no idea" what might arrive.

Homegrown hacks

Unsurprisingly, EMF had a distinctly homegrown feel.

Local hackspaces and other groups set up large tents, and while the festival received some sponsorship (University College London, helped with funding the Arduino-powered delegate badges, for example) there was a notable absence of logos and corporate activity throughout the venue.

Festivalgoers send a text or a tweet to get connected to the plastic power huts

Participants in a yurt-building workshop would be using fibreboard "rescued" from Winchester College of Art, and in another corner a makeshift geodesic dome made of plastic sheeting and duct tape billowed - but no corners had been cut in providing enough power to service even the most high maintenance of hackers.

Two 30m-high masts were erected for the occasion, one at the campsite and the other in the car park of a data centre 2.5km away. They were linked by microwave but there was also a fibre connection between Milton Keynes and Docklands in East London playing its part.

The infrastructure team had been hard at work on the tech spec since June.

"As long as people don't complain about the internet being too slow, we're happy," said Nat Morris modestly.

Mr Morris' real pride and joy was the network of adapted WCs, which opened to reveal rows of sockets and an all important wi-fi box. Despite their purpose they were all delivered fully stocked with toilet paper.

The infrastructure team tent was a thriving mission control, with flatscreen monitors displaying usage graphs and a large server stack tucked behind a curtain possibly once designed to be denote a bedroom.

"It's the kind of thing you'd normally find in a data centre, not a field," said Mr Wareing with a hint of pride.

Eager inventors

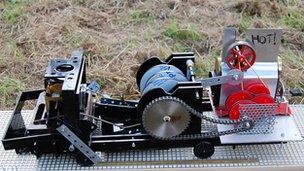

EMF delegate Chris Paton's "tank" is controlled by a Wii nunchuk and may travel at 15 miles per hour

Engineering student James Glanville attended the festival without his creation - he built his own 3D printer but was deterred from bringing it by the logistics of the park-and-ride travel arrangements.

"It probably cost about £300 to make but it's paid for itself three or four times over by selling things I've made from it," he said, pointing to a 3D-printed smartphone case.

In the next tent Chris Simpson, an "ethical hacking" student from Northumbria University, was looking forward to learning how to solder.

Jim MacArthur spent two years perfecting his mechanical Turing machine - powered by steam and controlled by ball bearings. It's a bit temperamental, he admitted, and "about a million billion times slower" than an average PC.

"I just always wanted to build a mechanical computer," he said.

Words of wisdom

Veteran tech festivalgoers Loz and Ian came to lend their support to the new event, having previously travelled to CCC (Chaos Communication Camp) in Berlin and HAR (Hacking At Random) in the Netherlands, both of which take place every four years and attract around 3,000 attendees.

Inventor Jim MacArthur admits his steam powered computer has "absolutely no" practical purpose

They had encouraging words for the organisers.

"Watch this space - in a couple of years EMF will be massive," said Ian.

"Through the internet, space and time don't have the same restrictions."

Before leaving, we paid a quick visit to the bar, which was constructed away from the tents, beneath the flyover of the M1 motorway.

I asked the barman why they chose that spot.

He fixed me with a long stare.

"Because it's awesome," he said, and returned to stacking glasses.

- Published28 July 2012

- Published26 April 2012