Betaville lets New Yorkers play real-world Sim City

- Published

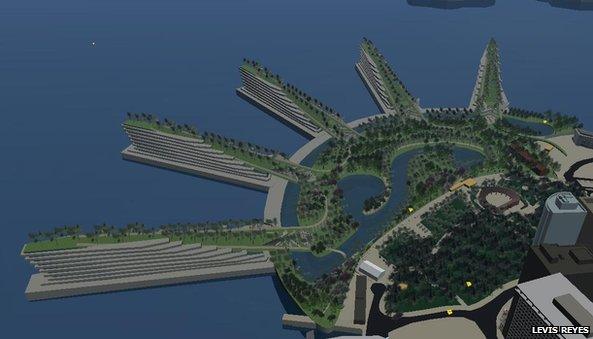

Pier-to-pier: Levis Reyes's design can be viewed and modified by others using the Betaville software

Looking like the Statue of Liberty's crown, five piers jut out of lower Manhattan's Battery Park. Filled with swirling waterways and trees, steps lead from the base of the crown to the top of its spiky, outstretched arms.

Designer Levis Reyes hasn't faced problems with planning permission for his flamboyant Liberty Piers, expanding out of Manhattan's Southern tip. The development is made up of pixels placed onto a map of New York on his computer.

Betaville is a multi-person open source platform which allows participants to build on empty spaces in New York City, like a real-life version of the popular game Sim City.

Players can walk around New York's streets - or fly over them - and stop at empty spaces which are shown by inverted yellow pyramids hovering over the vacant spot.

Users can also see the energy usage of some of the buildings in lower Manhattan and Brooklyn, as well as whether there is the capability of heating these using alternative fuels.

Betaville allows players to re-imagine the glamorous New York skyline

As one person designs a building on a spot, others can not only see the proposal but can also modify it. And this isn't just a fantasy world of wacky ideas; Betaville's developers are hoping to turn these designs into real buildings in the city.

Designer Carl Skelton came up with the idea for Betaville when he was the head and founder of the Brooklyn Experimental Media Center at New York University.

The Toronto native had seen too many failed attempts at getting the public involved in urban developments, and saw games as a good way to resolve this problem. He says the success of Sim City - the classic city-building simulation - suggested the effort had potential.

"One of the ways that Sim City was an inspiration was to see the number of human lifetimes that people paid for the privilege to be able to do this," Skelton says. "That told me something about the potential and the pent-up competence in these matters."

Creative construction

Betaville is one of several projects aiming to use games to involve communities in urban planning.

In Participatory Chinatown players complete tasks on a model of Boston's Chinatown, and are able to comment on developments.

Community PlanIt allows players to give feedback about their urban environment, placing its focus on Detroit and Boston.

But unlike the other titles, Betaville allows users to not only comment but to show precisely how they would like their city to be constructed.

It was developed with the help of a team at the M2C Institute for Applied Media Technology and Culture at the University of Applied Sciences, Bremen.

The institute's founder Martin Koplin believes that by playing games we can tap into a different part of our creativity.

The Aqua Pods are designed to create electricity by harnessing energy from the wind

"Things are somehow more intuitive," he says. "That is a very important part of play.

"A lot of things go on and that's very efficient, and if we can use this efficiency in serious environments then it will be better than if we don't."

Designer and Betaville fan Levis Reyes certainly believes the game unleashes his creative side.

"When I use Betaville I see it more as a tool that pushes your boundaries in design," explains the New York resident.

"It was never about what I was looking at but what could happen."

Together with Liberty Piers, his other proposals include Aqua Pods, huge cylinders built between Manhattan and New Jersey, with the two land areas being connected by routes for cars.

Long thin tubes, called convection zones, spiral up the inside of the cylinders, gathering nautical winds and generating electricity in the process.

In the lower parts of the structure are spaces for cars to park and residents to live. Each pod towers over New York's already tall skyscrapers.

Public approval

One might assume that many architects would not want the general public encroaching on their area of expertise, but many support Betaville and believe that it can also help professionals to do their job more effectively.

Jee Won Kim is an architect in New York specialising in the hospitality industry and residential spaces. He says that any project that affects the public requires their approval.

Betaville gives people a chance to see these proposals in their given context and to better understand how new buildings can fit into their communities.

"With enough renderings you can explain it," Mr Kim says, referring to meetings where architects show the public their proposals.

"But it's not quite the same as people being able to walk around it, fly over it and look at it themselves."

The plan is to turn areas like this, in Brooklyn, into attractive technology hubs

Mr Kim says the fact that people can not only view suggested schemes but also leave anonymous comments makes Betaville even more appealing.

"It's a great way to test your ideas," he says. "The more that we can engage the public and get their support, the better chances we'll have to get the project built."

In fact Mr Koplin laments the fact that without a program like Betaville the public only has the power to block proposals instead of actively moulding them.

"They don't have the power to design things but they have the power to stop things," he says.

Investors in Bremen for one are keen for citizens to be more involved in this process and there are plans to invite locals to use Betaville early next year.

"You can ask these people before what they want to have, or you start your project and listen to them in court when they stop your project," Mr Koplin explains.

"That is not something that we need in our time when people are emancipated.

"People should have more chances to be involved in the processes which concern society."

- Published27 June 2012

- Published30 September 2011