IBM's Watson supercomputer goes to medical school

- Published

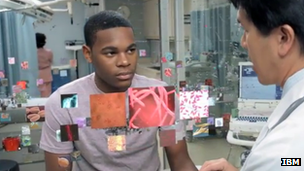

IBM suggests its Watson technology could one day become a commonplace diagnostic tool

IBM's Watson supercomputer is to help train doctors at a medical school in Cleveland, Ohio.

The machine gained fame when it beat two human contestants on the US quiz show Jeopardy last year.

Its technology will now be put to a more practical use helping students to consider challenging cases, external and offering potential diagnoses.

But some critics say the information artificial intelligence (AI) systems draw on is flawed.

IBM's announcement marks the US firm's latest effort to develop its product for the healthcare sector.

Watson is already involved in another project with a New York-based cancer centre, and is also being tested by health insurance provider Wellpoint to tailor treatments and claims forms for its members.

IBM believes the medical sector is one of the areas it will be able to make money from its artificial intelligence system. Others include customer service hotlines and the financial investment industry.

Computer clinicians

Watson is designed to "understand" natural language requests and then access vast quantities of unstructured data to find the best answers to questions.

In a healthcare scenario this would involve analysing both patient records and medical literature.

Watson has been designed to create a list of potential answers to a medic's request, rank them in order of likelihood and then present the most likely solutions along with information about how confident it is of their likelihood.

IBM said it would be used at the Cleveland Clinic Lerner College of Medicine to help students evaluate medical case scenarios and find evidence to support their judgements.

"Cleveland Clinic's collaboration with IBM is exciting because it offers us the opportunity to 'think' in ways that have the potential to make it a powerful tool in medicine," said the centre's chief information officer Martin Harris.

IBM, in turn, said it hoped that Watson would get "smarter" at handling medical language.

"Being able to work with the faculty and students at an organisation like Cleveland Clinic will help us learn how to more efficiently teach and adapt Watson to a new field through interaction with experts," said David Ferrucci, principal investigator of the Watson project.

IBM's Watson beat two Jeopardy champions in a special edition of the US game show in 2011

The effort builds on IBM's work with the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center's research unit in Manhattan, New York.

The two are working to develop an application that could help find the best treatment for a patient with lung, breast or prostate cancer. They hope to pilot an application with a wide group of oncologists by the end of 2013.

Money from medicine

The moves could be lucrative to IBM in the long run.

The US alone spent more than $2.6 trillion (£1.6tn) on health spending in 2010, representing 17.6% of its GDP, according to a recent report by the OECD, external (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development).

IBM's marketing materials suggest that as many as one in five diagnoses are incorrect or incomplete and nearly 1.5 million medication errors are made in the US every year.

Moreover it says the amount of medical information is doubling every five years making it harder for medics to stay across all relevant developments.

The company has indicated that it would request a "share of the value" of any benefit derived from its technology rather than a set fee.

Flawed data

IBM is not the only one aware of the sector's potential.

Researchers at the Clinical Decision Making Group at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) have also looked at applying artificial intelligence to medicine, while software such as Dxplain and Isabel already exist to help medics make the right call.

IBM has asked oncologists to test Watson-powered applications to help treat cancer

However, one healthcare tech specialist has suggested we are still 30 years away from computers becoming reliable diagnosticians.

Fred Trotter, technology director at the Cautious Patient Foundation, believes part of the problem is that much of the information that AI-driven systems have to draw on is flawed.

"It simply does not matter how good the AI algorithm is if your healthcare data is both incorrect and described with a faulty healthcare ontology," he wrote on the subject, external.

"My personal experiences with health data on a wide scale? It's like having a conversation with a habitual liar who has a speech impediment.

"I promise you we will have the AI problem finished long before we have healthcare data that is reliable enough to train it. Until that happens, imagine how Watson would have performed on Jeopardy if it had been trained on Lord of the Rings and The Cat in the Hat instead of encyclopaedias."

- Published31 July 2012

- Published17 February 2011

- Published14 June 2011