Nasa to test space-sleep colour-changing lights

- Published

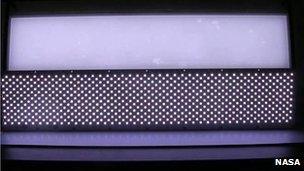

Researchers at Kennedy Space Center are already testing an SSLM lighting unit

Nasa is to test colour-changing lights on the International Space Station (ISS) as part of efforts to help astronauts on board sleep.

The US space agency will initially swap a fluorescent panel with a solid-state lighting module (SSLM) containing LEDs which produces a blue, whitish or red-coloured light depending on the time.

It says the move may help combat insomnia, external which can make depression, sickness and mistakes more likely.

The test is due to take place in 2016.

News site Space.com reported that the equipment is being made by Boeing and the project has a $11.2m (£6.9m) budget, external.

Body clock

Studies on Earth suggest humans and other creatures follow what is known as a circadian rhythm - a 24-hour biological cycle involving cell regeneration, urine production and other functions critical to health.

Research indicates that it is regulated by a group of cells in a portion of the brain called the hypothalamus which respond to light information sent by the eye's optic nerve, which in turn controls hormones, body temperature and other functions than influence whether people feel sleepy or wide awake.

LEDs in the lighting module can turn to blue to try to promote alertness

The aim of the experiment is to simulate a night-day cycle to minimise sleep disruption caused by the loss of its natural equivalent on the station.

When the SSLMs are coloured blue the aim is to stimulate melanopsin - a pigment found in cells in the eye's retina which send nerve impulses to parts of the brain thought to make a person feel alert.

Blue light is also believed to suppress melatonin - a hormone made by the brain's pineal gland which makes a person feel sleepy when its levels rise in their blood.

By switching from blue to red light - via an intermediary white stage - this process should be reversed, encouraging a feeling of sleepiness.

Nasa has previously warned sleep problems among its crews on other missions were also common.

"On some space shuttle missions up to 50% of the crew take sleeping pills, and, over all, nearly half of all medication used in orbit is intended to help astronauts sleep," it said in 2001, external.

"Even so, space travellers average about two hours sleep less each night in space than they do on the ground."

Evidence from Earth

Derk-Jan Dijk, professor of sleep and physiology at the University of Surrey, said Nasa's test reflects the latest findings closer to home.

"It hasn't been until recently that we started to realise that artificial light, as we see it or are exposed to it in the evening, will have an effect on our alertness and subsequent sleep.

The SSLM will replace a fluorescent panel on the ISS - one is seen here held by astronaut Michael Fincke

"It turns out there are receptors in the eye which are tuned toward blue light. Adding blue light to artificial lights visible during the day can actually help us to be alert, but if there is too much blue light in the artificial lights at night that may disrupt sleep.

"So, varying the spectral composition of light does make sense from a circadian perspective, and better regulating artificial sleep-wake cycles may indeed benefit astronauts' sleep in space."

Nasa adds there could be spin-off benefits for the population at large.

"A significant proportion of the global population suffers from chronic sleep loss," said Daniel Shultz at the Kennedy Space Center.

"By refining multipurpose lights for astronauts safety, health and well-being in spaceflight, the door is opened for new lighting strategies that can be evolved for use on Earth."

- Published3 December 2012

- Published8 May 2012