How will our future cities look?

- Published

Will we use flying cars to avoid the rush-hour in the cities of the future?

Imagine a city of the future. Do you see clean streets, flying cars and robots doing all the work?

Or perhaps your vision is more dystopian, with a Big Brother-style authoritarian regime, dark alleys full of crime, and people forced to live in hermetically sealed pods because war or some other disaster has rendered whole swathes of the city unliveable.

No-one really knows what the future holds, but the reality now is that our urban spaces are overcrowded and polluted.

Almost half of the world's population currently lives in cities, and by 2050 that is projected to increase to 75%, but what kind of city will they be living in?

The time is ripe, say experts, to start designing smarter urban environments, both new cities needed to sustain an ever-growing population, and retro-fits on the ones that we have lived in for centuries.

Greenification

If the cities of the past were shaped by people, the cities of the future are likely to be shaped by ideas, and there are a lot of competing ones about how such a futuristic urban space should look.

How do we make our cities greener?

Some of these revolve around the idea that smarter equals greener. Sustainability experts predict carbon-neutral cities full of electric vehicles and bike-sharing schemes, with air quality so much improved that office workers can actually open their windows for the first time.

Visions of a green city often include skyscrapers where living and office space vie with floating greenhouses or high-rise vegetable patches and green roofs, as we try to combine urbanisation with a return to our pastoral past.

Behind such greenification of cities lies a very pressing need.

"Cities are reaching breaking point," says Prof David Gann, who heads up Imperial College's Digital Economy Lab. "Traffic jams are getting worse, queues longer and transport networks more prone to delays, power outages more common."

Nerve centre

The answer may lie with big data and the so-called internet of things, where objects previously dumb are made smart by being connected to each other.

A network of sensors will, the argument goes, provide a host of data about how a city is performing. This will allow systems to be joined up and ultimately work more efficiently.

The internet of things could herald new developments that will give privacy experts nightmares, such as Minority Report-style digital signage - billboards that communicate with passers-by with personalised messages.

But it will also bring unimaginable new services to citizens, thinks Prof Gann.

Technology companies such as Siemens, IBM, Intel and Cisco, believe that the cleverest cities will be those that are hooked into the network.

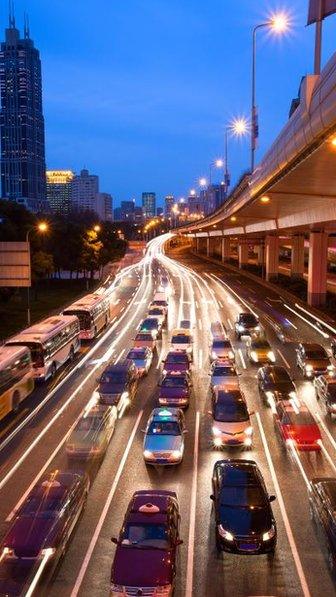

Many cities want to make traffic systems smarter

IBM currently has 2,000 projects ongoing in cities around the world, from crime prevention analytics in Portland, Oregon, to water databases in California, to smarter public transport systems in Zhenjiang, China.

Its flagship project is in Rio de Janeiro, where it has built an operations centre, which it describes as the "nerve centre" of the city.

Built initially to help deal with the floods that regularly threatened the city, it now co-ordinates 30 government agencies and provides mobile applications to keep citizens in touch with potential accidents, traffic black-spots and other city updates.

Crowd-sourcing

The fact that big corporations are becoming so heavily involved in designing city infrastructure has led critics to question how quickly such a city may, like the computer systems they are relying on, become obsolete.

Saskia Sassen, co-chair on the Committee on Global Thought at Columbia University and a leading expert on smart cities, draws parallels with the office buildings of the sixties, which she describes as "low-ceiling places now standing sad and empty as advanced technologies render them useless".

She is also concerned about privacy and the role that citizens will play in the grand plans of IBM and others.

"When does sensored become censored?" she asks.

IBM's Rick Robinson is quick to brush off concerns.

"The behaviour of a city is about the behaviour of citizens. Unless systems can become the fabric of their lives, nothing is going to change," he says.

Most of the projects IBM undertakes involve consulting with community groups as well as city councils, and any data-collecting schemes require the consent of users, he said.

He points to a project the firm completed in Dubuque, Iowa, where households were offered access to information about their water consumption.

The majority quickly changed habits and saved water when confronted with the data. Interestingly those also given access to their neighbours' information were twice as likely to make changes.

The power of the crowd will be crucial to the cities of the future, thinks Carlo Ratti, MIT's head of Sense-able Cities. He sees a battle ahead between what corporations want to sell to cities and what citizens actually need.

The power of the crowd will be important as cities get smarter

"Truly smart - and real - cities are not like an army regiment marching in lockstep to the commander's orders," he says.

"They are more like a shifting flock of birds or shoal of fish, in which individuals respond to subtle social and behavioural cues from their neighbours about which way to move forward."

As smart cities move from concept to reality, Ovum analyst Joe Dignan has a word of caution for those hoping to grab a piece of the action.

"Companies produce videos of glass houses of lovely people doing Minority Report-style stuff, but show me how this will help people sitting in their council flat 20 storeys in the sky?"

His words echo those of American author and urbanist Jane Jacobs who warned several decades ago: "Cities have the capability of providing something for everybody, only because, and only when, they are created by everybody."

Those building the cities of the future may do well to heed that advice.