Why air traffic control still needs the human touch

- Published

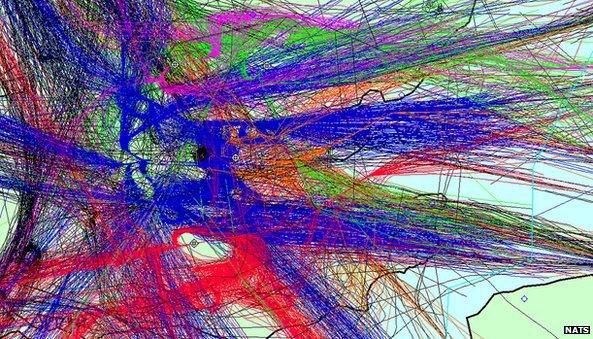

Each coloured line on this map represents an aircraft flight which either took off or landed in the south east of England on one day in July 2011

With 2.2 million flights a year to look after and 200,000 square miles (518,000 sq km) of airspace under its watchful eye, there's rarely a quiet moment when you're on duty at National Air Traffic Services (Nats).

In November 2011 life got a little easier for some of the organisation's 1,900 air traffic controllers when a bespoke new computer-based tool called iFACTS was introduced to the main control room at its Hampshire headquarters.

Years in the making, the rigorously tested software has been designed to take some of the complex manual calculations out of air traffic control.

Each green dot represents an aircraft in Nats airspace

"iFACTS, based on Trajectory Prediction and Medium Term Conflict Detection, provides decision-making support and helps controllers manage their routine workload, increasing the amount of traffic they can comfortably handle," trumpets the Nats website.

What this means is that iFACTS uses data from both aircraft and Nats itself to calculate flight paths, ascent and descent details.

It can also identify potential collisions, working around 18 minutes ahead of real time, and spot any unexpected behaviour by individual aircraft, highlighting potentially dangerous situations in the sky.

It has been a big success, according to Nats.

So why is it nowhere to be seen in their most demanding operation of all?

In the London control room, all five of the capital's airports are under separate supervision from the rest of Nats' domain, which includes Wales, Scotland, Northern Ireland and most of England.

This small area of the south east sees by far the largest concentration of air traffic, and the 18 minute window required by iFACTS is a luxury here, explained Nats General Manager Paul Haskins.

"It would light up like a Christmas tree," he said. " It's designed to manage large airspaces."

"It would think every flight was on a collision course. It's not like the States - Chicago airport has nothing around it for 300 miles (482km). In the UK airports are very close."

For this reason there is one key difference between the London and national air traffic control rooms - and the first clue is the noise.

In the London area there's a constant low-level clacking noise in the background, reminiscent of the typing pools of yore.

The London air traffic controllers still use paper strips because of the sheer number of aircraft they deal with

It is not the click of a computer mouse but the shift of brightly coloured plastic holders, organised in rows in front of each air traffic controller.

Each holder contains a printed strip that represents one aircraft. Details such as the pilot's call sign, speed, altitude, destination and a short-hand scribbled record of all instructions issued, are on the strips.

As the aircraft nears its destination or leaves the airspace, the controller manually moves the strip further down the desk until it is no longer under Nats guidance - either because it has descended below radar - 600ft (183 metres) in London - or successfully made its way into somebody else's domain.

"I wouldn't say any controller is better than technology," said Mr Haskins.

"But in the London control room the controllers can move more aircraft."

"Do you redesign the airspace around the technology or do you redesign the technology to fit the airspace?"

With a missed slot on a Heathrow runway costing its owner £500,000, Nats cannot afford to slow down. iFACTS may one day be able to speed up, but there is no such thing as a beta launch in this frontline sector.

"When you implement technology in air traffic... it has to be 99.999 percent working," said Mr Haskins.

Nats looks after 200,000 square miles of airspace

"It takes a lot longer to develop."

So although none of the air traffic controllers actually have eye contact with their charges - Nats HQ is about 70 miles (112km) from London, in Swanwick, Hampshire - their presence is still very much required.

Part of that need for the human touch is psychological, admitted Mr Haskins.

"Controllers and pilots talk to each other. I've got a piece of kit that knows what the controller is doing and the autopilot is also filing data. Couldn't they just talk to each other?" he said.

"Well yes - but to have an aircraft with 400 people in the air and no person looking after it just doesn't sound right. Would you want to get on board a UAV (unmanned aerial vehicle)?"

As well as wanting to know they are there, plenty of actual people want to be air traffic controllers themselves. Nats receives 1,000 applications for every 20 places on its four-year training scheme.

Candidates must pass initial psychometric tests, and successful recruits face an extra 18 months under human supervision if they wish to work on the London beat.

Perhaps the happiest marriage between man and machine exists among the organisation's 1,000 engineers.

"These days they aren't the guys with the spanners," said Paul Haskins.

"They're the guys with the laptops."

- Published21 September 2012