Raspberry Pi and the rise of small computers

- Published

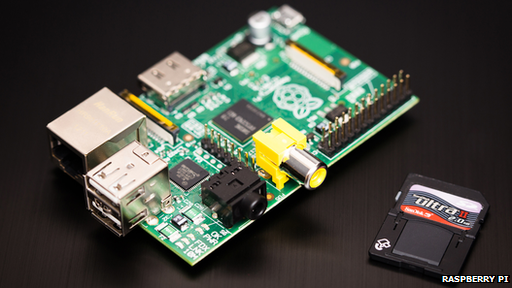

The Raspberry Pi is just one of many tiny computers now available

If small is beautiful, then in recent months the computer world has been burgeoning with beauty thanks to the growing number of teeny, tiny machines being released.

The Raspberry Pi has led this pack, purely because more than a million of them have been sold since orders started being accepted on 29 February 2012. Also available at this lower end of the market are devices from VIA, Rikomagic, Mele, Texas Instruments and Hiapad.

The loveliness does not stop there, as many others, such as FXI, Xi3, Zotac and even Intel, are producing dinky devices. Intel's contender, called the NUC or Next Unit of Computing, is about the size of a box of 80 teabags.

These small devices had emerged because of "massive changes" in the way people used computers, said Ranjit Atwal, research director at market analysis firm Gartner.

Intel says its NUC is suited to being a media hub or to power interactive kiosks

It used to be the case that people bought one computer to do everything, said Mr Atwal.

"Now," he said, "you buy the device to match your particular need."

In the same way that people buy a smartphone to browse on the move, if they want to try their hand at coding, they opt for the Raspberry Pi or one of its rivals.

Similarly, if they want a home media server for their DVDs, they pick Intel's NUC or perhaps something from Zotac or Xi3.

The prices of these small form factor machines varies widely but all these gadgets can, with a little help from a few add-ons and peripherals, do anything that used to require the services of a fully functioning, and quite hefty, desktop PC.

"There are a lot of tiny PCs out there in the market place," said Intel spokesman John Deatherage. "There's a growing spectrum of people needing computer power in a small form factor."

There were two main reasons for the emergence of small PCs, he said. One aesthetic and one technical.

The aesthetic reason was that computers had begun emerging from spare rooms and box-rooms and were taking up residence in living rooms. In some of those cases, people did not want a "beige box" squatting on their carpet, he said. Far better to have something small and unobtrusive.

Those machines being used in front rooms and other places were not "replacements" for the family PC but "were going where the need was felt", he said.

The technical trend is linked to the driving force of the computer world: Moore's Law.

Coined by Intel co-founder Gordon Moore, this economic law states that the number of transistors that can be placed on a chip for the same cost will double roughly every two years. More transistors in a smaller space typically translates to more power.

Chip development, memory density and a host of other technological innovations meant that now small did not mean puny, said Mr Deatherage.

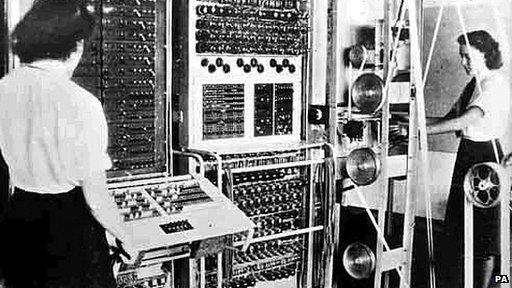

The first computers had to be very big

Power game

This, said James Gorbold, former editor of Custom PC, stood in sharp contrast to the situation barely a decade ago that emphasised size and brute force.

"Five to 10 years ago there was a trend towards really big machines," he said. "Hulking great gaming PCs filled with multi-coloured lights that needed water cooling."

"Now," he said, "the market has matured. People want something a bit more stylish and discrete."

It's matured thanks to the growing move to portable computing, which emphasised low power components, he said.

Less power going in means less heat coming out and removes the need for fans and other devices to cool the hot chips and other components doing all the hard work.

Many of the components found in small form factor PCs were more commonly found in phones, tablets or laptops, said Mr Gorbold.

For instance, the chip at the heart of the Raspberry Pi is more usually found in a handset. Similarly, hard drives and other components used in small machines from Dell, Apple and many others were initially developed for use in laptops.

Intel, in particular, said Mr Gorbold, had worked hard to reduce power consumption across all its processors for years, making it possible to put them in little boxes that do not need cooling.

For Mr Atwal, from Gartner, the shift to smaller PCs was also an indicator of the reality of the broader PC market.

"Over the last 10 years, who has made money in the PC world?" he asked. "It's Microsoft and Intel."

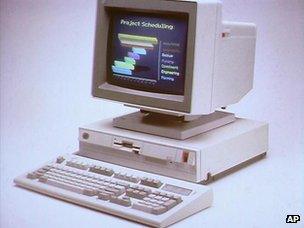

IBM's early PCs established the look of the desktop "beige box"

By contrast PC makers, he said, were operating on razor-thin margins and struggled to prosper, let alone think about new products.

"This means their ability to innovate is more and more limited," he said.

Increasingly, PC box shifters relied on Intel and other component makers to do the innovation for them. This reduced their risk and left them less exposed should they back a trend that did not catch on with consumers.

This, Mr Atwal said, helped to explain the current wave of "experimentation" in the PC market that had led to the emergence of lots of different types of small machines.

"It's one thing doing the innovation and its another entirely to position and market the final product," he said.

- Published5 February 2013

- Published8 January 2013

- Published9 August 2012

- Published29 January 2013