Where does television broadcasting go from here?

- Published

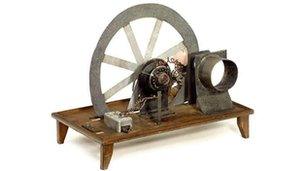

John Logie Baird may not have realised the extent of what could be possible following his first demonstration

With the BBC almost entirely divorced from Television Centre - the home of TV for decades - many innovators are already looking at what could be making waves, or pixels, in the future.

Since October 1925, television has moved a long way from the 30-line image of Stookie Bill, the ventriloquist's dummy, external.

By 1935, after some years of testing, there were around 2,000 Baird Televisors in use, costing £100 per set (the price of a small car), a year before the BBC began its Television Service.

Now 97% of the UK adult population consume content from over 500 channels on a TV set, according to Ofcom, external.

But the departure from Television Centre leaves a lot of memories behind, particularly in its news coverage.

"The very first day I arrived at Television Centre in my little car, I drove up to the gate and I remember feeling absolute goose flesh," says Angela Rippon, a former BBC newsreader.

"Walking in to the main reception was one of those days that will live with you forever. There were no computers, just typewriters, banks of televisions everywhere."

While these images conjure memories, it is not the way most modern newsrooms could be described.

"I think television has taken advantage of the wonderful technology changes," Rippon says.

Angela Rippon and Nick Higham revisit her old TV news studio

"When I started, we didn't really have satellite links, we had to book satellite time. You can be in your front living room and you're on the front line of a battle happening in Afghanistan."

Yesterday's news?

News may travel fast but, in technological terms, it certainly takes a long time to progress from an idea to a mainstream success.

Many of tomorrow's ideas are decades away from adoption.

Baird's Televisor from the 1920s could not easily be mistaken for a modern TV set

Since the early 1900s, patents were filed for proposals for colour television but it was not until 1928 that Baird managed to demonstrate it for the first time.

On 3 March 1966, the BBC announced plans to broadcast television in colour - an innovation led by David Attenborough, the then controller of BBC Two.

Just over a year later, the small number of Brits with the technology to watch a colour picture, could see it in their homes for the very first time.

The first national colour broadcast was carried out by NBC in the US in 1954.

It was not until 1972 that colour programmes formed the first all-colour season. And that kind of steady progress is still seen in content adoption today.

"In 1983, when I joined, one of the first things being worked on was the possibility of new high definition (HD) TV systems," says Graham Thomas of BBC Research and Development.

"It's ironic that's something I'm still involved in, though the decimal points have moved a bit. 1080 HD is the current standard. Resolutions four or eight times that - 4K or even 8K systems - are being worked on."

House of Cards

Even with the web, where things notoriously evolve at a quicker rate, it is a long process.

It is not just how content looks that changes but what it is recorded on

In the mid 1990s, ideas around what TV on the web could do were already being discussed but it is only now that bespoke online drama is seen to be gathering pace - notably with Kevin Spacey's starring role in Netflix's House of Cards and the growth of YouTube.

It is widely believed that the next seismic shift for broadcasting will be actually streaming TV content through internet services.

This is not as iPlayer does now but as the primary method of watching content on the TV. Similar to the recent move from analogue to digital, the next shift is expected to move all broadcasting from digital to 'streamed live' from the internet.

The difficulty is predicting when that will be the main way people watch content - with complex decision-making about its cost-effectiveness as a replacement for current digital services, usage and efficiency compared to other ways like satellite.

This could mean five years, 15 years or even 50. Like the move towards colour and high definition, these things take time.

Where does that leave the TV studio, how TV is made and how it is viewed?

"I started work as film for news was dying," says Guy Pelham, live editor of BBC News.

"If anyone had told me that within a short amount of time, I would get something the size of a phone and I could go live for TV, go live for radio, shoot edit and send short pieces, people would have thought I was mad."

But it's not just the BBC that has changed. Commercial broadcasters have had to move just as fast to cope with technological demands and opportunities.

"We were the first broadcaster to move to digital," says Luke Bradley Jones, Sky's brand director, TV products.

"We were the first to offer an integrated PVR - Sky+ as it's better known, the first to offer a national high definition service and, most recently of all, to launch a dedicated 3D channel."

Walking round EastEnders?

With each new development comes that moment when the audience see something they have never seen before.

"To get the wow factor, everything's got to build on what's come before. We need to go beyond big colour screens with a speaker either side," says Thomas.

A more interactive TV set that puts the power in the viewer's hands could be on the distant horizon

"In a world of finite resources, we're not going to do something just because we can. We want to produce something that will be really useful rather than just a flash in the pan."

And innovators certainly have big ideas about what could be in the distant future, though these ideas are currently only research.

"What if we let a viewer freely walk around a football pitch and look at things from every angle or explore different rooms in the Queen Vic?," says Thomas.

"It would be a different approach than just 3D images. We're a little way off that yet but it's a nice driving force."

But do these technological advances risk harming broadcasting?

At least one former correspondent thinks so.

"What's happened is technically brilliant, but what you're lacking is authenticity in the sense of actually being there," says Martin Bell, the former former war reporter and MP, and now Unicef ambassador.

"You know when it all went pear-shaped? When the mobile phone arrived on the front line. Before then, all the editors could do would be to run the piece or drop it.

"The foreign editor asked me what my report was about. I said: 'It's about one minute and 42 seconds.' You couldn't get away with that any more could you?"

- Published23 January 2012

- Published10 January 2013