Bacteria power 'bio-battery' breakthrough

- Published

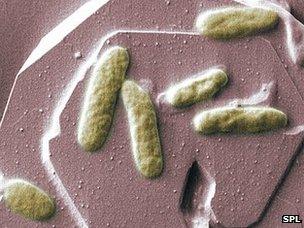

The shewanella bacterium is found in lakes and rivers all over the planet

Bacteria could soon be acting as microscopic "bio-batteries" thanks to a joint UK-US research effort.

The team of scientists has laid bare the power-generating mechanism used by well-known marine bacteria.

Before now it was not clear whether the bacteria directly conducted an electrical charge themselves or used something else to do it.

Unpicking the process opens the door to using the bacteria as an in-situ, robust power source.

Power play

"This was the final part of the puzzle," said Dr Tom Clarke, a lecturer at the school of biological sciences at the University of East Anglia (UEA), who led the research. UEA collaborated with the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory in Washington on the research project.

Before now, Dr Clarke told the BBC, the bacterium being studied had been seen influencing levels of minerals in lakes and seas but no-one really knew how it did it.

The bacterium, Shewanella oneidensis, occurred globally in rivers and seas, he said. "They are in everything from the Amazon to the Baltic seas," said Dr Clarke.

The strain used by the researchers was taken from a lake in New York.

"Scientists noticed that the levels of iron and manganese in the lake changed with the seasons and were co-ordinated with the growth patterns of the bacteria," Dr Clarke said.

However, he added, what was not known was the method by which the bacteria was bringing about these changes in mineral concentrations.

To understand the mechanism, Dr Clarke and his collaborators made a synthetic version of the bacterium and discovered that the organism generated a charge, and effected a chemical change, when in direct contact with the mineral surface.

"People have never really understood it before," he said. "It's about understanding how they interact with the environment and harnessing the energy they produce."

Understanding that mechanism gave scientists a chance to harness it, said Dr Clarke, and use it as a power source in places and for devices and processes in inaccessible or hostile environments.

"It's very useful as a model system," he said. "They are very robust, we can be quite rough with then in the lab and they will put up with it.

A paper about the research was published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

- Published25 March 2013

- Published28 January 2013

- Published30 October 2012