Why can't the UK produce world-beating tech companies?

- Published

- comments

It was a birthday party and the mood was celebratory.

Luminaries past and present from across the UK's computing industry had gathered to mark the 75th anniversary of the Cambridge University computer laboratory.

But there was also one nagging question. Why does a city and a country which have played such a huge part in the history of the computer, still produce so few world-class technology companies?

A strange question to ask, perhaps, in a lecture theatre packed with successful alumni of the lab, some from companies like ARM and CSR which have thrived in Cambridge. After all, this is a city where academia and business have combined very fruitfully in the past two decades.

But in a lecture on what he's learned about innovation, Mike Lynch - who's the founder of another Cambridge technology success story, Autonomy - bemoaned the fact that all the brilliant work done by the university's scientists had failed to translate into many big hitters in the FTSE-100.

Just one UK computer business had made it into the FTSE, he told us, and that was Sage, the Newcastle-based accountancy software firm. "Our universities are second to none," he said. "But they're failing to translate the gold coming out of them into economic growth."

(It now strikes me that Dr Lynch is ignoring the fact that the chip designer ARM is in the top third of the FTSE-100 - but maybe he doesn't count it as a computing company?)

He suggested that many companies with excellent technology got to a certain stage and then they or their backers lost confidence, selling up to American firms. We were, he suggested, producing great R&D labs for overseas firms to exploit rather than going on to turn high quality research into products for global markets.

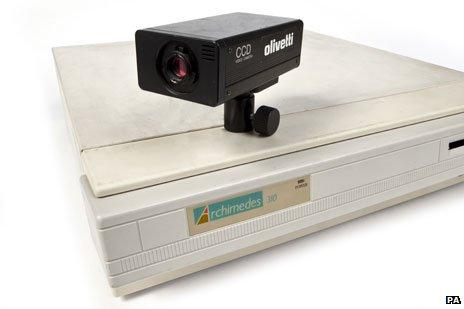

The world's first webcam, produced at Cambridge Computer Laboratory

Dr Lynch, of course, eventually sold Autonomy to America's Hewlett Packard and is now embroiled in a row over just what his company was really worth. But his point was that more firms needed to stay independent long enough to create a lasting infrastructure in Britain, even if they ended up in foreign ownership.

Others in the audience then joined a discussion about the way forward. Lord Broers, a distinguished engineer and former vice-chancellor of Cambridge University, was worried by how little we spent on research and development as a country compared to rivals - 1.7% of GDP in the UK, as compared to 2.8% in Germany and 2.9% in the United States. "We're underspending by billions, mainly in industry," he said.

There were the usual worries about a gap in capital for technology companies - plenty at the start, then very little when they wanted to make the leap into the big league. And there were calls for government to to think more about using its own procurement budgets to help UK firms in the way the US did - for the different tech clusters, from Cambridge to Bristol to London's TechCity, to collaborate better; even for The Sun newspaper to start celebrating computer scientists on page three.

Mike Lynch's main concern, however, was about the teaching of STEM subjects - science, technology, engineering and maths - in secondary schools where he felt we were falling behind. He cited as an example the scarcity of girls taking A-Level physics.

We had brilliant graduates coming out of places like the Cambridge computing laboratory, he said, but that supply could dry up, and we needed a wider hinterland of skilled people. Those worries about a skills gap opening up are now commonplace amongst many in Britain's hi-tech industries.

But Cambridge, the birthplace of computers from the Edsac to the BBC Micro, has at least produced an attempt to address that problem with the Raspberry Pi, which aims to inspire a new generation of computer scientists.

That continuing spirit of innovation should provide some cause for optimism that we can find ways of turning world-class science into world-beating businesses.