The book's not finished yet

- Published

- comments

How is the digital revolution affecting the book trade?

If you travel on trains packed with commuters staring at tiny mobile phone screens rather than books, or wander along high streets now devoid of bookshops, you might think it was in a sorry state.

But the Publishers' Association annual statistical digest, published today, seems to paint a different picture.

The industry had a record year for sales, up 4% to £3.3bn. 2012 was the year when the digital revolution really took hold, with sales up 66% to £411m and fiction e-reading growing even faster, up 149%.

As for the physical book, long thought to be under threat from all those Kindles, Kobos and Nooks, reports of its demise may be premature. Sales fell just 1% to £2.9bn, and in some genres, notably children's books, sales actually rose.

The figures also show that the pace at we're switching from physical to digital books varies according to the type of title. Apparently, 26% of fiction sales are digital, whereas for non-fiction books the figure is just 5%, and for children's titles, 3%.

Why? Well perhaps for fiction it is only the words that matter, and they can be rendered as well or better in digital form, whereas for something like a glossy cookery book or an illustrated children's book, the physical object still delivers a much better experience.

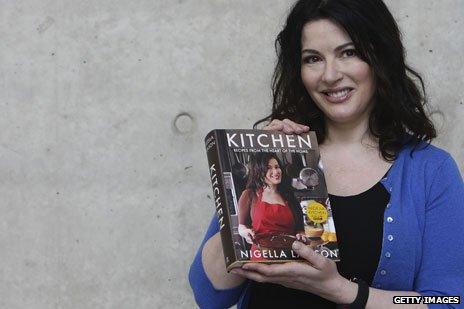

Nigella Lawson: withstanding the digital threat?

What does this mean then for the pace of publishing's digital revolution and its impact on readers and authors?

A few weeks ago Michael Serbinis of the e-reader maker Kobo told me he reckoned that 90% of reading would eventually be on digital devices.

You won't be surprised to hear that Richard Mollet of the Publishers' Association is betting on a lower figure - somewhere between 30% and 50%. But however rapid the shift to e-readers, publishing seems to be weathering digital climate change better than some other media industries.

But what about authors? I was surprised to hear from JoJo Moyes - a bestselling writer of women's fiction - that nearly half of the sales of her latest book were in a digital format. And each digital sale earns her a few pennies more than the royalty she gets from a physical book sale purchase.

Mind you, not all authors are happy - they point to the much lower costs of producing digital books and wonder how publishers still justify taking such a large cut.

The publishers' response is that they have to spend large sums defending authors from the threat of piracy.

British publishers have reported record sales for 2012, despite the recession and the rise of e-readers

JoJo Moyes has some sympathy with that argument: "I've got a Google alert set up and every day it tells me about a new torrenting site offering free copies of my book. I pass them on to my publisher to deal with. "

Still, neither publishers nor authors seem to have seen their incomes damaged significantly by either piracy or the wider digital revolution. Readers, meanwhile, have a wider choice, and perhaps the prospect of lower prices - although many will grumble that e-books should be a whole lot cheaper.

For bookshops the news is not so good. Independent book stores continue to close, as readers turn to online giants like Amazon for both physical and digital books.

That is making our high streets just a little less interesting, so it's a vicious circle where going out and browsing for books or anything else becomes less attractive than sitting at home and shopping online..

But overall, 2012 seemed to show that the British public still loves books in all their variety, and is prepared to pay to enjoy them.

We hear plenty of doom and gloom from the old media industries about the ravages of the digital revolution - but publishing seems determined to look on the bright side.