Can computer games change the world?

- Published

Computer games are usually seen as a hobby not expected to influence thinking in the real world

Serious games, which have addressed issues as varied as the Middle East conflict through to sexual coercion among teenagers, have gained the attention of governments around the world. But can they really directly affect the issues they cover?

Computer games are regularly criticised as a waste of time and for offering graphic depictions of violence.

Regardless of the truth of the opinion, a form of game offering a different side has increased in popularity - the serious game.

"The story of games, in popular terms, is a story about adolescent boys in dark bedrooms," says journalist Tom Chatfield, who has developed computer games.

"It was only really when the interfaces of games at the start of the 90s, became visually significant and serious that people started to realise that what they were doing might be a reflection of the world, in the same way as a book or a film or an article is."

Serious games focus on real-world situations and events in a way that it is hoped educates the players and provokes debate in a community.

Three billion hours a week are spent on playing games, mainly as a pastime rather than having any large global effects, and developers hope some of that time can be harnessed for the greater good.

One game, a World Without Oil, explored the theory that oil was running out and offered players the chance to come up with ways to deal with the impending crisis.

"In America, there was an undercurrent where we just said 'this is a bubble, this is going to pop'," says Ken Eklund, designer of the game.

"Oil did hit $200 a barrel a few months later so things were really happening.

"These stories get put together and become this coherent multi-threaded, multi-authored story about what an oil crisis might really be like, emotionally, not just about who has oil and who doesn't and how much productivity is being lost. What does it feel like?

"The actual spirit of the game, from the players' point of view, is they said 'we are creating something which the government should pay attention to'. As a matter of fact, the government did.

"The federal government was very interested, especially the people responsible for disaster response.

"The players are proud of what they have created as a narrative."

Government 'games expert'

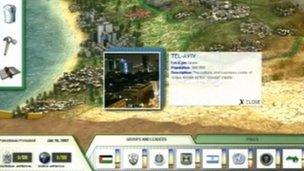

Games have been created about a wide variety of issues. The Middle East conflict has been addressed by Games for Change, in the hope to inform people of both sides of the discussion.

In Peacemaker, the player can choose to act for either side in the Middle East conflict

"The big idea was it was about perspective," says Asi Burak, co-president of Games for Change.

"You could choose either to be either the Israeli prime minister or the Palestinian leader. Just by that choice and playing a whole different game from each perspective, we could show you the war through a very different lens.

"In terms of impact, what I discovered was the game was more than anything else, a great opener of discussion. I learned that people don't discuss it in daily life in Israel in the West Bank or in Gaza."

With games having increasing influence, governments are becoming more interested in being involved. In the US for example, there is a games expert attached to the White House.

But the real question is what can change after a large number of people play through a serious game.

Using the example of the Middle East conflict, the troubles are still ongoing. But can a game really be expected to inspire tangible changes in such a big issue?

"It's always very difficult to come up with a direct chain of cause and effect," says Mr Chatfield.

"In terms of games feeding into society, I find it very difficult to offer a huge example of 'this game changed the world'. That's a very dangerous promise to make. It's a promise that you will almost inevitably fail to deliver."

The problem with these promises could be that direct analysis of the results from a game is rarely fully carried out.

"One of the things that has never really been done well is evaluation of outcomes," says Mary Matthews, former strategy director at Blitz Games Studios.

Games have been created offering teachers a computer game to use during sex education lessons

"We now have web games that have millions of hits on their site and people take the fact that people have engaged with that play as being successful.

"Nobody at that time was looking at measurable outcomes. They played it but then what?"

One place it is hoped measurable outcomes will be achieved is in the classroom.

A virtual gameshow offering teenage players a decision about what constitutes sexual coercion is currently being trialled in some sex education classes in Coventry and Warwickshire, produced by the Serious Games Institute and Coventry University.

"One of the things that's very striking when you spend time in a classroom of teenagers is just how easy it is for them to get bored or distracted," says Dr Katherine Brown, leader of the Sash Research Group at Coventry University.

"The more innovative you can be with what techniques you use, the more likely you are to be successful in delivering the education you are trying to get across.

"Having that technology does instantly engage the young people in the classroom. It's completely novel to them that their teacher would use this kind of technology to deliver a lesson on sex education."

Which could bring us back to the beginning of computer games, if they really were about adolescent boys in dark bedrooms, this time with a much more serious point.

- Published21 January 2013

- Published23 April 2013