Logging our lives with wearable tech

- Published

- comments

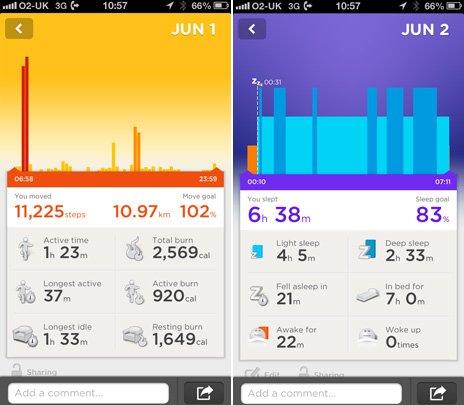

Last night I slept for six hours and 38 minutes, with four hours and five minutes of that being light sleep, and deep sleep of two hours and 33 minutes.

On Saturday, I walked 11,225 steps, was active for a total of one hour and 23 minutes, and burned 2,569 calories.

Why should you - or I for that matter - be interested in that data, which was collected by one of a number of wearable activity monitoring devices which are now entering the market? That's a question we explore in a film for Newsnight about the rise of wearable technology and its implications.

There are now all sorts of gadgets, from the Nike Fuelband to the Jawbone UP, which measure your physical activity. Then there are others which take photos constantly to give you a record of what you've seen throughout the day, devices like the Autographer and Memoto which are about to go on sale.

Then of course there is Google Glass, the poster child for wearable technology, even though it is many months away from being in the hands of consumers.

All of these devices will generate a huge amount of data, and there is already a group of dedicated technophiles who see a way of using it. They call the practice of recording the minutiae of their activities "life-logging" or "the quantified self".

Rory Cellan-Jones tried lifelogging kit in 2013 for Newsnight

We met one of them, Paul Boag, a web designer in Dorset who has always been an early adopter of technology. He is one of the guinea pigs in a research project run by the computing department at Goldsmith's College, London, which is looking at the impact of wearable computing on our lives.

Paul wears the Jawbone UP wristband, which measures his activity during the day and monitors his sleep at night. He is also very focused on collecting, recording and analysing lots of other data that tells him more about himself. He has suffered from depression in the past and believes this process is helping him.

"What excites me is taking control of my own life," he told me. "The more I know about my body the more aware I am. We often go through life in a stupor and one thing to the next but this makes me aware of myself."

It's not just individuals taking advantage of this new method of self-examination. Companies too are taking interest, and this is where the privacy issues around the way the data is used begin to look very tricky.

The cloud technology firm Appirio has issued many of its staff with the UP wristband, tracking everything from their food intake to their sleep patterns. It is a voluntary scheme, and Lori Williams who runs the European division of the American business says it's already proving valuable for employees and the firm.

"We've had about a hundred employees that have lost a stone or more in the last several months. Last month alone, we collectively walked about 17,000km (10,563 miles). So it's making us not just better employees but I think better people. And I think that's the benefit."

The company has also managed to cut its health insurance costs in the United States by showing its insurer the impact of this life-logging plan.

But, although the scheme is voluntary at this company, there are bound to be concerns that this kind of monitoring will become standard. Ten years from now, how will an employer using life-logging technology view those who choose to opt out?

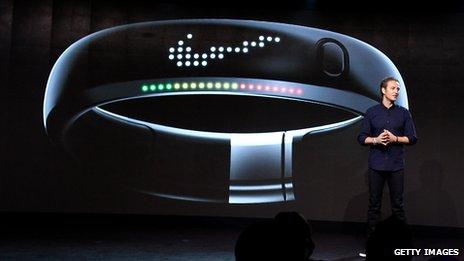

Nike's Fuelband is one of many activity-monitoring gadgets

And there are wider questions about who will own all the data generated by these new devices and how careful they will be with it. Companies like Google are already promising tight privacy controls on their products. There'll be no facial recognition, for instance, in Google Glass.

But Nick Pickles of Big Brother Watch believes we all need to be very cautious about such promises: "There is a tension between privacy and profit, and profits usually win," he told us. "The nightmare is, the data is in the cloud and it's out of your control. The company owns it so you don't. With facial recognition, someone takes a photo of you in the street and goes home and they can build up a huge picture of your life without you ever knowing about it."

Of course, the great unknowable in all of this is just how far the appetite for wearable technology will stretch beyond early adopters like Paul Boag. But if we do all end up wearing devices that record our every step and take pictures of every person we meet, then we will need to think carefully about both the etiquette and the ethics of logging our lives.