What does Prism tell us about privacy protection?

- Published

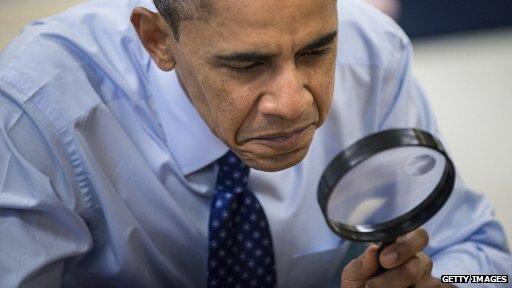

President Obama has defended US surveillance tactics, but whistleblower Ed Snowden said he was "horrified" by the activities

Both international governments and the world's biggest tech companies are in crisis following the leaking of documents that suggest the US government was able to access detailed records of individual smartphone and internet activity, via a scheme called Prism.

Ed Snowden, a 29-year-old former technical worker for the CIA, has since revealed himself to be the source of the leaks in an interview with the Guardian news website.

US director of national intelligence James Clapper described the leaks as "extremely damaging" to national security, but Mr Snowden said he had acted because he found the extent of US surveillance "horrifying".

What could the US government see?

According to the documents revealed by Ed Snowden, the US National Security Agency (NSA) has access on a massive scale to individual chat logs, stored data, voice traffic, file transfers and social networking data of individuals.

The US government confirmed it did request millions of phone records from US company Verizon, which included call duration, location and the phone numbers of both parties on individual calls.

According to the documents, Prism also enabled "backdoor" access to the servers of nine major technology companies including Microsoft, Yahoo, Google, Facebook, PalTalk, AOL, Skype, YouTube and Apple.

These servers would process and store a vast amount of information, including private posts on social media, web chats and internet searches.

All the companies named have denied their involvement, and it is unknown how Prism actually works.

National Security Agency (NSA) Director Keith Alexander said that the eavesdropping operations have helped keep Americans secure - yet cannot provide details. "If we tell the terrorists every way that we're going to track them, they will get through and Americans will die," he said

Some experts question its true powers, with digital forensics professor Peter Sommer telling the BBC the access may be more akin to a "catflap" than a "backdoor".

"The spooks may be allowed to use these firms' servers but only in respect of a named target," he said.

"Or they may get a court order and the firm will provide them with material on a hard-drive or similar."

What about data-protection laws?

Different countries have different laws regarding data protection, but these tend to aim to regulate what data companies can hold about their customers, what they can do with it and how long they can keep it for - rather than government activity.

Most individual company privacy policies will include a clause suggesting they will share information if legally obliged - and include careful wording about other monitoring.

Facebook's privacy policy, for example, states: " We use the information [uploaded by users] to prevent potentially illegal activities".

Are we all being watched?

UK Foreign Secretary William Hague said "law abiding citizens" had nothing to fear

The ways in which individual governments monitor citizen activity is notoriously secretive in the interests of national security, and officials generally argue that preventing terrorism over-rides protecting privacy.

"You can't have 100% security and also then have 100% privacy and zero inconvenience," said US President Barack Obama, defending US surveillance tactics.

Senator Dianne Feinstein, chairwoman of the Senate Intelligence Committee, said that phone records were only accessed by the NSA in cases where there was reason to suspect an individual was connected with al-Qaeda or Iran.

Speaking to the BBC UK Foreign Secretary William Hague said that "law abiding citizens" in Britain would "never be aware of all the things... agencies are doing to stop your identity being stolen or to stop a terrorist blowing you up".

Does it make a difference which country you live in?

User data (such as emails and social media activity) is often not stored in the same country as the users themselves - Facebook for example has a clause in its privacy policy saying that all users must consent to their data being "transferred to and stored in" the US.

The US Patriot Act of 2001 gave American authorities new powers over European data stored in this way.

This method of storage is part of cloud computing, in which both storage and processing is carried out away from the individual's own PC.

"Most cloud providers, and certainly the market leaders, fall within the US jurisdiction either because they are US companies or conduct systematic business in the US," Axel Arnbak, a researcher at the University of Amsterdam's Institute for Information Law, told CBS News last year, external after conducting a study into cloud computing, higher education and the act, external.

"In particular, the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Amendments (FISA) Act makes it easy for US authorities to circumvent local government institutions and mandate direct and easy access to cloud data belonging to non-Americans living outside the US, with little or no transparency obligations for such practices - not even the number of actual requests."

Are other governments involved?

UK Foreign Secretary William Hague has so far refused to confirm or deny whether British government surveillance department GCHQ has had access to Prism.

It is not known whether other governments around the world have been either aware of or involved in the use of Prism, which is reported to have been established in 2007.

In a statement, the EU Justice Commission said it was "concerned" about the consequences of Prism for EU citizens and was "seeking more details" from the US authorities.

"Where the rights of an EU citizen in a Member State are concerned, it is for a national judge to determine whether data can be lawfully transmitted in accordance with legal requirements (be they national, EU or international)," said a spokesperson for Justice Commissioner Vivane Reding.

What does this mean for internet use?

Edward Snowden (picture courtesy of the Guardian) said he "did not want to live in a society that does these sorts of things"

William Hague insists that law-abiding citizens have nothing to worry about, and there is no legal way of "opting out" of monitoring activity carried out in the name of national or global security.

However privacy concerns about information uploaded to the internet have been around for almost as long as the internet itself, and campaign group Privacy International says the reported existence of Prism confirms its "worst fears and suspicions".

"Since many of the world's leading technology companies are based in the US, essentially anyone who participates in our interconnected world and uses popular services like Google or Skype can have their privacy violated through the Prism programme," says Privacy International on its website, external.

"The US government can have access to much of the world's data, by default, with no recourse."

Edward Snowden, the source of the leaked documents, said he had acted over concerns about privacy.

"I don't want to live in a society that does these sort of things… I do not want to live in a world where everything I do and say is recorded," he told the Guardian.

- Published10 June 2013

- Published8 June 2013

- Published7 June 2013

- Published7 June 2013

- Published6 June 2013