TEDGlobal: Future vaccines could be delivered via patch

- Published

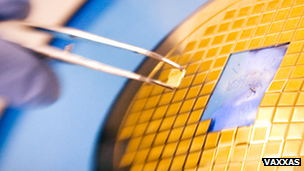

The Nanopatch contains an array of thousands of vaccine-coated projections that perforate the skin

A skin patch that can deliver vaccines cheaply and effectively has been shown off at the TEDGlobal conference in Edinburgh.

Using a patch rather than a needle could transform disease prevention around the world, said its inventor.

Prof Mark Kendall said the new method offered hope of usable vaccines for diseases such as malaria.

Other medical experts welcomed the news, but warned it might be unsuitable for some patients.

Old technology

It was fitting that Prof Kendall delivered his talk in Edinburgh where, 160 years previously, Alexander Wood had lodged the first patent for the needle and syringe.

"The patent looked almost identical to the needles we use today. This is a 160-year-old technology," he said.

It is also one that, alongside clean water and sanitation, has played a key role in ensuring longer lifespans around the world.

But he said the technology could be overdue for an update.

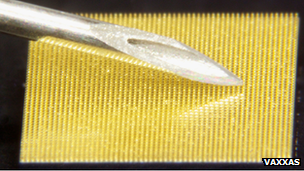

The nanopatch overcomes some of the more obvious disadvantages of syringe-given vaccines such as needle phobia and the possibility of contamination caused by dirty needles.

But there are other reasons why the method could be transformative, said the professor.

Thousands of tiny projections in the patch release the vaccine, which is applied in dry form, into the skin.

Prof Kendall has set up a company to commercialise the nanopatch

"The projections on the nanopatch work with the skin's immune system. We target these cells that reside just a hair's breadth from the surface of the skin," said Prof Kendall.

"It seems that we may have been missing the immune sweet spot which may be in the skin rather than the muscle which is where traditional needles go."

In tests at his laboratory in Queensland University, Brisbane, the nanopatch was used to administer the flu vaccine.

Researchers noticed that the immune responses for vaccines administered with the nanopatch were completely different to those given by a traditional syringe.

"It means that we can bring a completely different tool to vaccination," said Prof Kendall.

The amount of vaccine needed to be effective is much lower, up to one hundredth of the traditional dose.

"A vaccine that had cost $10 [£6.40] can be brought down to just 10 cents, which is very important in the developing world," he added.

Vaccine failure

Another major shortcoming of traditional vaccines is that, because they are liquid, they need to be kept refrigerated between the lab and the clinic.

"Half of vaccines in Africa are not working properly because refrigeration has failed at some point in the chain," said Dr Kendall.

When he told the TED audience that the vaccine for the nanopatch could be kept at 23C (73F) for up to a year, he elicited a huge round of applause.

The vaccine coating is stable at room temperatures meaning it does not have to be refrigerated

The news was given a more qualified welcome by the British Society for Immunology.

"This approach holds out hope for easy and large-scale vaccination, as it targets a type of immune cell, called the Langerhans cell, that is abundant in the skin," said Dr Diane Williamson.

"These cells avidly take up the vaccine and are able to kick-start the immune response.

"However, one of the potential issues with skin delivery is transit time and ensuring adequate delivery of the vaccine payload.

"Also there may be issues of tolerability of the patch in some people. However, if these issues can be overcome, the approach does hold out the potential to dispense with conventional needle-based 'intra-muscular' delivery."

The nanopatch will soon begin field tests in Papua New Guinea where vaccines are in short supply.

The country also sees the highest incidence of the HPV virus, which can cause cervical cancer.

Prof Kendall said that while he finds it hard to imagine a world without traditional needles and syringes, he is hopeful that the new method can be widely adopted.

"Let's hope for a future where millions of deaths a year from preventable diseases can be a historical footnote because of radically improved vaccines," he said.

- Published12 June 2013

- Published12 June 2013

- Published11 June 2013