The teenage radio enthusiasts who helped win World War II

- Published

There were about 1,500 so-called voluntary interceptors during WWII - civilians helping to intercept secret Nazi codes

To mark the centenary of the Radio Society of Great Britain, one of its members recalls how the amateur organisation played a key role in a covert operation to safeguard the country's independence.

One day, towards the start of World War II, a captain wearing the Royal Signals uniform knocked on a British teenager's door.

The 16-year-old was called Bob King. When he went to greet the visitor, he had no idea that soon he would become one of Britain's so-called "voluntary interceptors" - some 1,500 radio amateurs recruited to intercept secret codes broadcast by the Nazis and their allies during the war.

"The captain asked me if I would be willing to help out with some secret work for the government," remembers Mr King, now 89. "He wouldn't tell me any more than that.

"He knew that I could read Morse code - that was the essential thing."

The captain had heard about Mr King through the RSGB - an organisation for amateur radio enthusiasts. Many of its members were youngsters curious about the possibilities offered by tinkering with radio receivers.

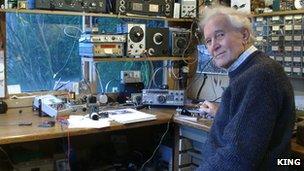

Bob King was only 16 when he was recruited by MI8

During World War II, dozens were recruited by MI8 - a division of the British Military Intelligence department, and a cover name for the now-defunct Radio Security Service (RSS).

The purpose of their work was to intercept secret wireless transmissions by German and Italian agents in Britain.

Mr King signed the documents the captain had handed to him, which, he says, basically stated that he had "read them and knew what would happen to me if I opened my mouth too wide".

He was then given the instructions to scan shortwave bands and write down Morse code he discovered on a piece of paper.

Cracking codes

Mr King worked from his home in Bicester, Oxfordshire, but voluntary interceptors were scattered all around Britain.

Many used their own radio equipment to eavesdrop on enemy messages.

The RSS's original headquarters had been in Wormwood Scrubs, London but in 1940 it was moved 12 miles (19km) north to the village of Arkley when German air raids threatened its efforts to analyse and sort the intercepted data.

By mid-1941, the new base, Arkley View, was receiving about 10,000 message sheets a day from its recruits.

"I worked for five years scrutinising the logs that came in from the other amateurs - thousands of log sheets with the signals which we knew were wanted, and you could only know it from experience," remembers Mr King.

Arkley View became the main office of the RSS during the war - it is here that the intercepted data was sorted and analysed

"We knew it wasn't Allied army air force, we knew it was German or Italian - various things gave that away, but it was disguised in such a form that it looked a bit like a radio amateur transmission.

"We knew it was highly important, everything was marked 'top secret,' but only many years later we discovered that it was German secret service we were listening to.

"Of course you didn't ask questions in those days, otherwise you'd be in real trouble."

Encoded messages were transmitted to Bletchley Park in Buckinghamshire, the UK's former top-secret code-cracking centre.

Once decoded, the data was sent to the Allied Commanders and the UK Prime Minister, Winston Churchill.

Secret listeners

Just like thousands of code-crackers working at Bletchley Park during the war, voluntary interceptors had to keep quiet about what they were doing.

Mr King says that they were not even allowed to mention anything to their families. His wife only found out about her husband's secret past in 1980 - more than three decades after he had stopped his interception activities.

Some voluntary interceptors had regular meetings during and after the war - but they were not allowed to talk about their work to anyone else

Now that they are allowed to speak up, he seems disappointed that this ghost army of secret civilian listeners has not been given more credit for the part it played in the Allies toppling the Nazis - including the successful invasion of Normandy.

"The main success of the voluntary interceptors was in knowing what the enemy intelligence services were doing, what they believed and didn't believe, and we managed to manipulate them in that way through the agents that we controlled," he says.

John Gould, the organiser of the RSGB's centenary celebrations, agrees. "Not only did the intercepts provide a huge amount of traffic, but through the skills of the radio amateurs 'fingerprinting' the Morse code of the German operators, supported by direction finding, the UK was able to monitor movements of the German forces," he says.

"The intelligence gained from these intercepts was reported to have been of significant importance to control enemy agents and other matters such as sabotage and deception activities."

- Published20 March 2013

- Published11 February 2013

- Published19 April 2012