Computational photography: the snap is only the start

- Published

Pelican makes a phone camera that allows two subjects to be in focus but not objects in between them

Imagine a camera that allows you to see through a crowd to get a clear view of someone who would otherwise be obscured, a smartphone that matches big-budget lenses for image quality, or a photograph that lets you change your point of view after it's taken.

The ideas may sound outlandish but they could become commonplace if "computational photography" lives up to its promise.

Unlike normal digital photography - which uses a sensor to capture a single two-dimensional image of a scene - the technique records a richer set of data to construct its pictures.

Instead of trying to mimic the way a human eye works, it opens the activity up to new software-enhanced possibilities.

Pelican Imaging is one of the firms leading the way.

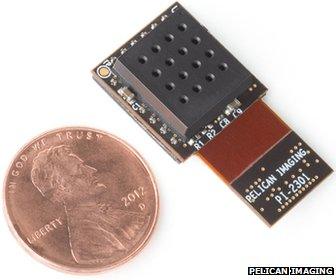

Pelican's component is less than 3mm (0.1in) thick, making it thinner than most normal smartphone cameras

The California-based start-up is working on a handset part, external which contains an array of 16 lenses, each attached to either a blue-, red- or green-colour sensor, which link up to a chip that fuses the data they produce together.

"You end up with a standard Jpeg-image that has a depth map of the scene that allows you to identify where all the edges of all the objects are right down to human hair," chief executive Christopher Pickett tells the BBC.

A companion app uses this information to let the snapper decide which parts of their photo should be in focus after they are taken. This includes the unusual ability to choose multiple focal planes.

For example a photographer in New York could choose to make the details of her husband's face and the Statue of Liberty behind him sharp but everything else - including the objects in between them - blurred.

"Because we have no moving parts we also have super-fast first shot, as we're not hunting for focus," adds Mr Pickett. "You get the perfect picture as you just don't miss."

Another firm, Lytro, already offers similar functions on its own standalone light field camera - but Pelican suggests offering the tech via a component small enough to fit in a phone will prove critical to its success.

Nokia has already invested in Pelican, leading to speculation it will be among the first to offer the tech when it becomes available next year.

For now, high dynamic range (HDR) imaging offers a ready-to-use taste of computational photography. It uses computer power to combine photos taken at different exposures to create a single picture whose light areas are not too bright and dim ones not too dark.

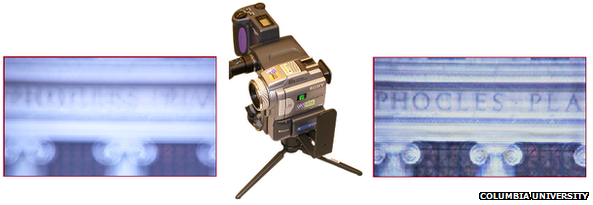

Moving images in the background can create problems for current HDR-enabled smartphones

However, if the subject matter isn't static there can be problems stitching the images together. Users commonly complain of moving objects in the background looking as if they're breaking apart.

One solution - currently championed by chipmaker Nvidia - is to boost processing power to cut the time between each snap.

But research on an alternative technique which only requires a single photo could prove superior.

"Imagine you have a sensor with pixels that have different levels of sensitivity," explains Prof Shree Nayar, head of Columbia University's Computer Vision Laboratory.

"Some would be good at measuring things in dim light and their neighbours good at measuring very bright things.

"You would need to apply an algorithm to decode the image produced, but once you do that you could get a picture with enormous range in terms of brightness and colour - a lot more than the human eye can see."

Even if current HDR techniques fall out of fashion, computational photography offers other uses for multi-shot images.

Photo two

Last year US researchers showed off a process which involves waving a compact camera around an object or person to take hundreds of pictures over the space of a minute or so.

The resulting data is used to create what's called a light field map, external on an attached laptop.

Software makes use of this to render views of the scene, letting the user pick the exact vantage point they want long after the event has ended.

Another technique involves analysing two photos taken in quick succession, one with flash the other without.

"You can use this to work out what features of the image are shadows," explains Dr Martin Turner, a computer vision expert at the University of Manchester.

Microsoft suggests software can be used to improve the look of flash photography

Microsoft has filed a patent for this idea, external saying the information could be used to make flash photographs look less "jarring" by automatically improving their colour balance, removing ugly shadows cast by the bright light and treating for red-eye.

Ultimately you end up with what looks like a highly detailed low-light image that doesn't suffer from noise.

Some of the most exotic uses of computational photography have been pioneered by Stanford University where researchers came up with a way to "see through", external dense foliage and crowds.

By positioning dozens of cameras at different viewpoints and processing the resulting data they were able to create a shallow-focus effect that left the desired subject sharp but obstructing objects so blurred that they appeared transparent.

Photo One

Their research paper suggested surveillance of a target as a possible use for the tech.

"They spent $2m [£1.3m] to build this great big camera array and it took a team of dedicated grad students to run the thing," says Prof Jack Tumblin, a computational photography expert at Northwestern University, near Chicago.

"It was a wonderful lab machine, but not very practical."

Prof Tumblin is currently trying to develop a budget version of the effect using only a single camera.

His theory is that by taking lots of shots from different positions, with the lens's exact location recorded for each one, he should then be able to use software to remove an undesired object from the final photograph. The caveat is that the thing involved must be static.

Prof Tumblin aims to be able to remove all traces of an object from his photos

Perhaps the biggest potential benefit of computational photography isn't new gimmicky effects but rather the ability to capture the best two-dimensional shot possible.

One area of research is to create a high-quality image that currently requires a heavy lens containing several precision-polished glass elements to take it - but to do so with a smaller, cheaper, less complex part.

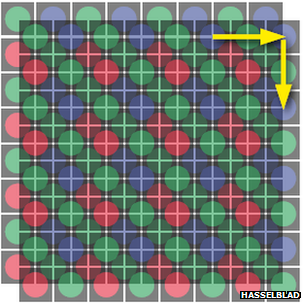

By moving its camera sensor Hasselblad captures red, blue and green image data for each pixel point

The idea is to stop trying to avoid any imperfections in the image cast onto the sensor but rather control what kinds they are, limiting them to ones that can be fixed with software.

Another technique involves taking shots in quick succession and moving the sensor as little as half-a-pixel between each one before combining the information to create a "super-resolution" image.

Hasselbad already uses this on one of its high-end cameras to let its 50 megapixel sensor create 200MP photos.

And there's the suggestion that building a hybrid device which takes takes both stills and high-speed video, external simultaneously could solve the problem of camera shake.

"The purpose is to get an exact measurement of how the photo has been blurred," explains Prof Tumblin.

"If the video camera part focuses on some bright spot off in the distance it can be used to work out the trajectory. That lets blur caused by your hand moving in random ways become quite reversible."

A hybrid camera can gather video data to help fix blur caused by camera shake in its still images

- Published11 July 2013

- Published11 July 2013

- Published1 May 2013