Nokia: The rise and fall of a mobile giant

- Published

Nokia was the dominant player in mobile phones for more than a decade

From market domination to sell-off in less than 10 years. As Microsoft swoops in to buy Nokia's mobile business for £4.6bn, what happened to Finland's most beloved company, and why would Microsoft take it on?

Whenever you turned on one of Nokia's legendary handsets, you always got the same thing: that famous signature logo, holding hands.

And for more than one generation, it was hand-holding Nokia did best - carrying people through, bit by bit, the mobile revolution.

Because way before we were shouting, "Damn you autocorrect", we were grappling with new-fangled predictive text.

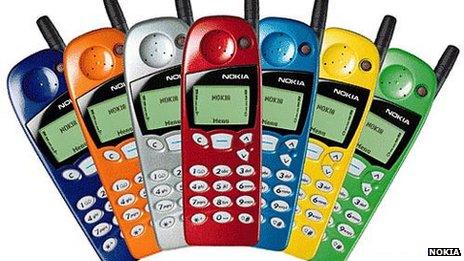

In the days before highly customisable backgrounds and operating systems, there were swappable (and very, very cool) fascias.

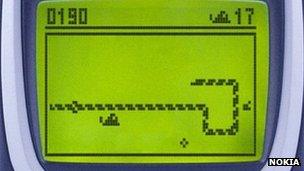

And, of course, more than 12 years before anyone ever made birds angry, there was the mobile game to rule them all: Snake.

Nokia were by no means the first company to release a commercially available mobile phone, but it was the first to do it really well, and with true mass appeal.

"Back in the 1990s there weren't these other big brands," says Ben Wood, an analyst at CCS Insight.

"Nokia were so dominant. People didn't talk about what brand, it was just about the number, 3210, or whatever you had. They took users on a journey."

Era of complacency

So far, so good - but then one presentation changed everything.

"Complacency had kicked in," Mr Wood continues, "they felt they could do no wrong.

Many people's first experience of mobile gaming was the highly addictive Snake

"Then all of a sudden, in January 2007, Steve Jobs walked on to a stage and pulled an iPhone out of his pocket and changed the world forever."

The fall was swift. According to figures from analyst firm Gartner, Nokia's smartphone market share in 2007 was a dominant 49.4%. In subsequent years, it was 43.7%, then 41.1%, then 34.2%.

In the first half of this year, it had plummeted to just 3%.

Many blame this decline, at least in the initial stages, on Symbian, the firm's mobile operating system. It was, to paraphrase a welter of expert opinion, simply not up to the job.

"They missed the importance of software," Mr Wood says.

"Nokia make great phones, they still do. They went through this incredible decade of innovation in hardware, but what Apple saw was that all you needed was a rectangle with a screen, and the rest was all about the software."

Windows gamble

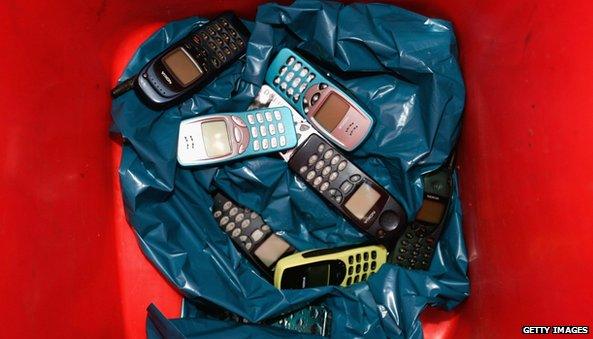

It took just a few years for Nokia phones to go from being the must-have handset in your pocket, to being the long-forgotten handset, nestled in that eternal graveyard of the mobile phone - the kitchen drawer.

So why would Microsoft spend £4.6bn on a business that looks like it's on the way out?

To use a romantic analogy: they were the only two left at the party who hadn't paired up with anyone.

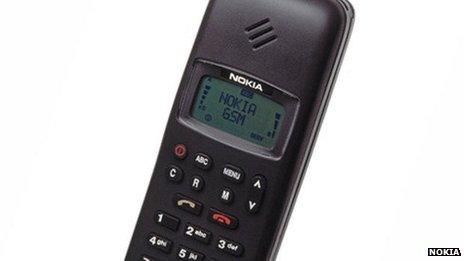

Launched in 1992 and weighing a colossal 495g (1.1lb), the 1011 was the first mass produced GSM phone

The interchangeable covers gave the 5110 a wide appeal

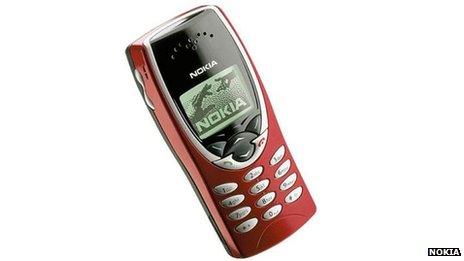

Weighing just 79g, the lightest handset on the market in 1999. Customisable covers helped popularise the 8210

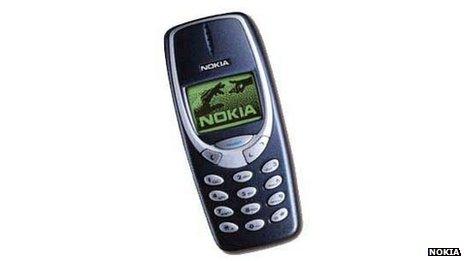

The 3310/3330, released in 2000, among the best-selling phones of all time, with 126 million units produced

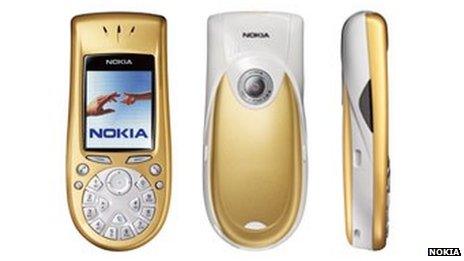

An early smartphone experiment, the 3650 was released in 2002. It ran Symbian Series 60, but the unique circular keypad was not popular

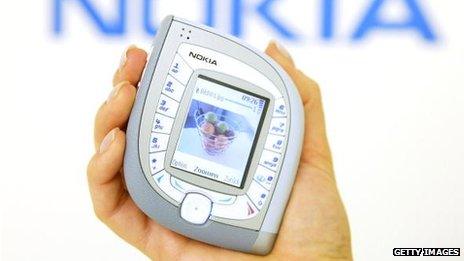

One of Nokia’s first 3G handsets, the 7600 unveiled in 2003. It was part of the ‘Fashion’ series – but the design experiment didn’t appeal to users

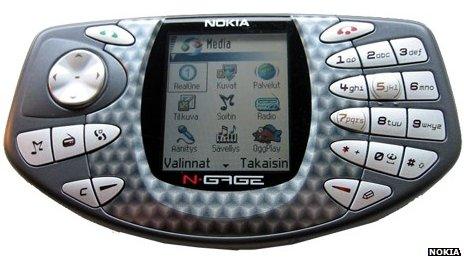

The N-Gage was Nokia's attempt to break into the handheld gaming market, released in 2003. Not as popular as expected due to limited number of games and clunky design

"They were left dancing together, and thought they might as well go home," jokes Mr Wood.

"Microsoft was left with few alternatives, because they've got to succeed in mobile."

But far from facing an awkward morning after, buying up Nokia's phone business does make a lot of sense for both parties.

For starters, Nokia's flagship smartphones already use Windows Phone, Microsoft's operating system which, although still way behind its competitors, is at least gathering some modest momentum.

With Nokia's phone business moving in-house, Microsoft boss Steve Ballmer tells the BBC that the acquisition means they can "improve the agility" of innovation in mobile.

Roberta Cozza, an analyst with Gartner, agrees.

"I think that for Microsoft to compete in today's mobile market against Apple and Google they needed to be more than just a software company," she tells the BBC.

"Depending on the way they figure out the organisational structure with the Nokia people inside, they can allow Nokia to innovate around hardware, and get input from them on the operating system, and gain the opportunity to deliver more competitive products."

Additionally, Ms Cozza says, Microsoft gains key expertise in emerging markets.

"Nokia has know-how of this market that goes beyond the hardware," she says.

Reinventing Nokia

It's hard to imagine Nokia as anything other than a mobile phone company.

But a peek into its history shows a deep-rooted ability to reinvent itself. Indeed, there was a time when Nokia was famous for its durable rubber boots and car tyres.

Microsoft chief executive Steve Ballmer: "This is a big bold step forward"

"I wouldn't be against the 'new' Nokia managing to pull something off," says CCS Insight's Mr Wood.

Clues to the company's future lie with recent strategic movements.

One recent deal, for example, saw Nokia buy up Siemens' share in Nokia Solutions and Networks, a mobile broadband company.

Also remaining in Nokia's portfolio is its well-regarded maps division - Here - which is the mapping software of choice in 80% of cars that feature built-in dashboard navigation.

And then of course, there are those all-important patents. Thanks to Nokia's early dominance, it owns many crucial patents on which the mobile industry relies.

Forbes estimates that Nokia's portfolio is worth somewhere in the region of $4bn (£2.6bn).

So while this may signal the beginning of the end for Nokia as a well-known brand in the hands of millions, many believe it is in good shape to move forward and build as a key player behind the scenes - without the distraction of chasing mainstream popularity.

"Essentially what's left is a new Nokia," Mr Wood concludes.

Follow Dave Lee on Twitter @DaveLeeBBC, external

- Published3 September 2013

- Published3 September 2013

- Published26 August 2013

- Published26 August 2013

- Published11 July 2013

- Published23 August 2013