Graeme Obree challenges speed record with radical bike

- Published

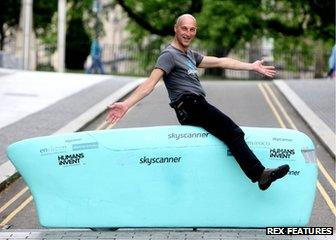

Graeme Obree has up to four attempts to break the record over the course of the week

Former world champion racing cyclist Graeme Obree is attempting this week to set a new human-powered land speed record with Beastie - a very unconventional bike.

He will travel head first and face down, his chin 2cm (0.8in) from the front wheel, his eyes peering out of a small peephole.

The 47-year-old from Ayrshire in Scotland has up to four attempts to beat the current record of 83mph (133km/h) at an event being held at Battle Mountain, Nevada.

Yet, despite the potential scale of the achievement, much of the cycling world appears unmoved because of its traditional attitude that muscle-power should take precedence over mechanical innovation.

Revolutionary design

Mr Obree's life has already been immortalised in the film, The Flying Scotsman, but his torpedo-shaped bike may mean his name soars to fresh heights.

Beastie was initially tested using a transparent shell known as a fairing

With its smooth shell of Kevlar and fibreglass, Beastie looks as though it has been made by Nasa. Yet it was constructed, says Mr Obree, "entirely by myself in my kitchen and a pal's workshop".

Beneath the slick carapace, it is a jumble of components which include a stainless steel saucepan, acting as a shoulder support, and parts from old bikes and roller-skates.

The truly revolutionary aspects are invisible: the position of the human being inside it, and the fact that Mr Obree will not be pedalling, but instead operating a couple of push-pull levers with his feet.

As for the position, whereas recumbent bikes typically see the rider lying on their back and travelling feet first, Mr Obree reverted to "first principles," wiping his memory of any existing ideas of bicycle design and thinking, simply, about the physics of movement.

He thought of a sky diver, since: "Going head first, with arms tucked in, is the most aerodynamically efficient position for a human being."

The challenge then was to design and build something that facilitated that; the lines of his drawings ended up permanently etched into his kitchen table.

Part of the prototype shell had to be cut away during a test run because the rain obscured Mr Obree's vision

His main fear is that Beastie, which has to be held up at the start and caught at the end, flips over mid-ride.

"I've covered the chainwheels and clunky bits, so that I'm not chopped up," he says.

But it remains a dangerous undertaking. "It's not tiddlywinks," says Mr Obree.

His latest challenge, as part of the World Human Powered Speed Challenge, is a typical Obree undertaking: perhaps even the one he was born to try.

As a racing cyclist in the 1990s, he was as renowned for his skills as an inventor and engineer as for his athletic prowess.

He designed two riding positions that revolutionised the sport - the first inspired by the downhill skiing tuck, the second by Superman. He also built his bikes, with his original machine - Old Faithful - using parts from an old washing machine.

It was on Old Faithful that Obree made international headlines by breaking the world hour record in Norway in 1993.

But the Union Cycliste International, the conservative body that oversees the sport and guards the traditional diamond-shaped design much like a gentlemen's club that insists on shirt-and-tie, took a dim view.

Mr Obree's chin is just 2cm away from Beastie's front wheel when it is in motion

They banned Mr Obree's original position, so he went back to the drawing board and returned with a second, with arms raised and extended like Superman in flight.

With the Superman position he won a second world pursuit title in 1995 but the UCI still weren't happy and banned that, too.

Arguably, it was Mr Obree more than anyone who forced the governing body to take a fresh look at the issue of bike design in the late 1990s.

At stake, they felt, was the principle of cycling as a test of athleticism rather than engineering, with the cautionary tale of Formula One, where some felt the balance had tilted too far the other way.

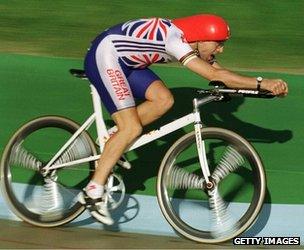

Mr Obree has previously competed on more traditional looking bicycles

But the response, which came in the so-called Lugano Charter adopted in 2000, was draconian.

The new rules meant that one-offs and prototypes were banned.

Parameters were set for the shape of frames and components, there were restrictions placed on riders' positions, and a weight limit of 6.8kg (15lb) was established for road racing bikes.

But many of the rules are vague and subject to interpretation.

When asked recently about the ambiguity by American magazine Velo, Pat McQuaid, the UCI president, responded: "The regulations were written in a philosophical way. They were written by philosophical types."

There is a growing clamour for a shake-up, not least from an ever-growing cycling industry frustrated at rules that stifle development.

Brian Cookson, the head of British cycling who is challenging McQuaid for the presidency of the UCI, said last week that the regulations in the Lugano Charter would be reviewed under his leadership.

Graham Obree's online video of how the Beastie works

"We limit [the manufacturers'] ability to put new products to market by arcane rules that prevent innovation," said Mr Cookson.

"As someone once said, the UCI give the impression they would be happy if all bikes looked like something [1950s Italian star] Fausto Coppi might have ridden. This is not to argue for a free-for-all but, by reforming the rules sensibly, we will open the sport up to new revenue streams and new audiences worldwide."

There are no such constraints in the world of human-powered vehicles, which is why Mr Obree might finally have found the perfect arena.

Here, the shackles are off and he has free rein to test his engineering skills as well as his athletic ability. As he put it: "This is not about human rules anymore. This is about the laws of physics and that is the only constraining factor."

Mr Obree says he is not worried about the dangers posed by his speed challenge

An imperfect build-up, including major surgery in April and weather-hampered test runs on less-than-smooth airport runways in Scotland, mean that Mr Obree admits his attempt on the record is "compromised" and that his original target of 100mph is unrealistic.

But he remains upbeat. "It's dictated by what the bike is capable of," he says.

"Unlike my hour record attempts in the 1990s, this is so much more about the bike than the rider.

"Having studied the physics of it, I do believe a human being in perfect physical condition, with perfect aerodynamics, a perfect drive-system, perfect air and atmosphere conditions, could do 100mph," he continues.

"On this occasion I don't think it's going to be me. But if I can up to the high 60s then sprint as hard as I can towards the world record, I'll just see what happens."

Former racing cyclist Richard Moore represented Scotland in the 1998 Commonwealth Games. He is the author of several books including Tour de France 100, a history of the French cycling competition.

You can follow coverage of the week's events at Humans Invent's website, external.