Grand Theft Auto: One of Britain's finest cultural exports?

- Published

- comments

The BBC's technology correspondent Rory Cellan-Jones reports on the latest instalment of controversial game series Grand Theft Auto.

William Shakespeare, Edward Elgar, The Beatles, James Bond... Grand Theft Auto?

The list of cultural icons from this "small island" is world-changing, formidable, unmatched - and so to put a video game into the same sentence as those mentioned above may be considered daring.

But as the latest instalment of the super-violent series hits the shelves around the world, many are taking a step back and assessing the cultural impact of a title that has changed not only the games industry, but perhaps even the entertainment business as a whole.

Because even before today's release of Grand Theft Auto 5, the GTA series has already sold more games than The Who have sold records, to use just one comparison.

Across the world, the franchise has shifted more than 135 million units since its 1997 debut.

"The cultural impact and artistic quality of the game also demonstrates just how far video games have come," remarks Richard Wilson, head of games industry trade body Tiga.

"[It] clearly shows they are now on a par with film, television and animation, and deserve to be treated as such."

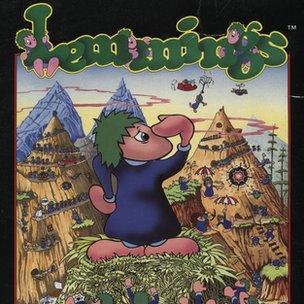

Lemmings

All in all, it's not a bad effort from what used to be a tiny company working out of Dundee.

Back in 1997, the company now called Rockstar North was known as DMA Design - and while most of us may not recognise that name, many will affectionately remember another of their worldwide smashes: Lemmings.

The highly-addictive point-and-clicker was a staggering success, and in its shadow, GTA wasn't exactly popular within the company.

"No-one really wanted to work on GTA," recalls Paul Farley, the title's level designer, in a documentary made for the Guardian, external.

The premise was simple: as the player, you could run around, partaking in all manner of criminality, with the intent of rising to the top of the gangster underworld by any grotesque means necessary.

Lemmings this most certainly was not.

Development on GTA, which was originally called Race 'n' Chase, began in 1995. It reached the shops in 1997, but not without controversy.

"Here was a game where you could be the bad guy," recalls David Kushner, author of Jacked: The Outlaw Story of Grand Theft Auto.

Before they made GTA, it was DMA's Lemmings that had been taking the gaming world by storm

"There were drugs, prostitutes, random violence.

"While those are the sorts of things we've seen for some time in other forms of media, books, films and so on, this was a problem for a lot of people, because they felt that children had to be protected from this content."

For an industry that was used to games being mostly for kids and nerdy adults, this was a massive awakening - and the backlash was immediate.

"People felt concerned that the player, just by playing this game, was somehow perpetrating the violence and actually being criminal," Mr Kushner remembers.

"When in fact, what they were doing was twiddling their thumbs and moving pixels around a screen."

What was not so well known was that many of the shocking stories found in the tabloid press were in fact planted there by publicist Max Clifford - whom DMA had hired to promote the title.

Society's 'black mirror'

There were calls to ban the game in several countries around the world. In some cases, they were successful, such as in Brazil. The ban was later lifted.

In the years to come, the series would be named by the Guinness Book of Records as the most controversial video game in history - an accolade based mostly on the number of column inches dedicated to the series.

But had the game simply been about violence, it would not have stood the test of time, argues Brian Baglow, a writer on the first title in the series.

"The games sector had always been very good at blowing stuff up - creating more realistic bullet holes - but they had no real cultural relevance.

"GTA on the other hand, as it's been set in a contemporary environment, it has acted like a black mirror set up against society."

In GTA5, that mirror lashes out at many aspects of today's popular culture, taking on foes including TV talent shows and social networking - a less-than-subtle dig at Facebook comes in the shape of "Lifeinvader", external.

Lifeinvader's strapline, if the point needed pushing home further, is: "Where your personal information becomes a marketing profile (that we can sell)."

Beyond this, the characters in GTA5 live in a post-recession world - and encounter all the miserable side-effects of it along the way.

The main brains behind the series - the slightly media-shy Houser brothers, Sam and Dan - perhaps modestly underplay the social commentary element of the series.

"It's up to us to make the best stuff we can make," Dan Houser told the Guardian, external.

"It's not necessarily up to us to shout from the rooftops about how clever we are, how progressive we are or how sophisticated we are. It's our place to make stuff that's as good as it can be."

Brit wit

All the games - bar an early London-based spin-off - are set in the USA. But crucial to the series' success is that the world the characters inhabit is peppered with a distinctly British outlook, argues Mr Baglow.

"It's one of the very few cultural exports from the UK that actually achieves this," he says, noting that while Rockstar has offices in several locations around the world, Rockstar North, where GTA is mostly developed, has remained in Scotland.

"What GTA does is it actually take the American culture as we understand it from movies - it's every gangster movie, it's every crime caper. It uses that, but keeps it very grounded with a British sensibility.

"This is a very large part of the influence of Rockstar North, based in Edinburgh - there's a tongue-in-cheek streak running throughout. That's something that people tend to miss."

But, British - or Scottish - humour aside, the games remain gratuitously and unapologetically violent.

There's no hiding, not even behind a deeper social commentary, that characters in GTA can be instructed to have a sex with a prostitute before beating her to death and stealing her money.

Yet with every new game it appears, in some markets at least, that the outrage is diminishing - both within those working in the media and others in political circles.

Mr Kushner says this may be put down to one simple thing: gamers have grown up.

"I think the gamers are now in power. People in their 40s and 50s - they don't feel threatened by games anymore.

"We've seen this cycle in other forms of media too. Elvis Presley - when he went on the Ed Sullivan Show, he was only shown from the waist up. People thought his swivelling hips were too outrageous."

Iconic future

So what next for the Grand Theft Auto series?

The fifth instalment is forecast to sell in the region of 25 million copies within the first 12 months of its release.

GTA5 is expected to sell more than 25 million copies in its first year

In terms of its profitability, it is widely accepted that GTA5 will be the first title in the franchise to allow in-game purchases - that is, ways to enhance the game by paying some more money.

And the game's online multiplayer mode is expected to see it achieve a new level of timelessness: no longer will the game be exhausted once all the missions are complete.

But whether the series will be held up in the future as a prime example of British creative culture is still open to much debate.

"I think it is iconic in so many ways," says Tom Chatfield, an author and academic in digital culture.

"It's the quality of it. It's not vacuous. The violence is gratuitous, of course - but there's a real quality there, a meticulousness - the makers are obsessional."

Mr Baglow is confident: "It's just a matter of time. We need people who have come through and are comfortable playing games, and don't see it as something freakish."

Follow Dave Lee on Twitter @DaveLeeBBC, external

- Published16 September 2013

- Published12 September 2013

- Published27 August 2013