Valve: How going boss-free empowered the games-maker

- Published

- comments

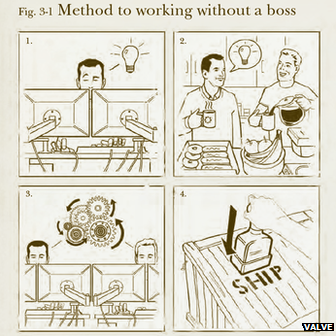

Valve believes high-performance workers tend to self-improve without a need for managers

Welcome to Flatland.

Imagine a company where everyone is equal and managers don't exist. A place where employees sit where they want, choose what to work on and decide each other's pay. Then, once a year, everyone goes on holiday together.

You have just imagined Valve.

The video games developer caused a stir when a handbook detailing its unusual structure, external leaked onto the web last year. Now, in a rare interview, it discusses its inner-workings.

"We're a flat organisation, so I don't report to anybody and people don't report to me," explains DJ Powers, speaking to the BBC on the sidelines of Edinburgh's Turing Festival.

Valve's employees often continue working on a game, adding features, after its release

"We're free to choose to work on whatever we think is interesting.

"People ask you questions about what you are working on. And the response is not to get defensive but to have that conversation and make sure that we're all invested in each other."

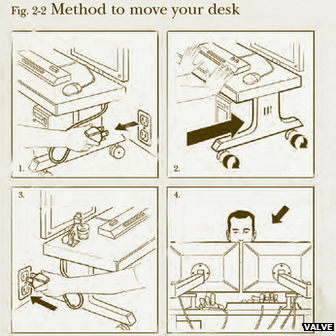

Even the furniture in Valve is unusual.

While other firms have fixed layouts, the workstations at the Bellevue, Washington-based company are fitted with wheels.

"We move around a lot and we don't want it to take a lot of time to do that," says Mr Powers.

"We form into teams based on need to complete a feature or complete a game, and then we disperse into new teams.

"The ability to be able to pick up and move and be in another office in 20 minutes as opposed to a day-and-a-half is really attractive.

Valve's somewhat eccentric handbook includes a guide to how to move its desks

"I've moved my desk probably 10 times in three years.

"You just wheel it out of the office and into the freight elevator and go up to whichever floor you need."

Valve's games - which include the Half-Life, Portal, Dota and Left 4 Dead series - are famed for both their quality and high sales.

Its online store, Steam, helped popularise the idea of a digital marketplace years before Apple's App Store.

Now some suggest its new Steam operating system could disrupt the games console market.

One might think the firm's set-up is a recipe for its staff to career off to their own personal passion projects. So how do its complex products ever emerge?

"One of the ways that things get done at Valve is that a critical mass does form," explains Mr Powers.

"There are lots of ideas about what is cool to work on.

"But unless you can find like minded people to work with, you will struggle to get enough resources you need to get it done."

DJ Powers worked at Electronic Arts before jumping ship to join Valve

Traditional management consultants might shudder at the implications, but Prof Cliff Oswick from Cass Business school - who has studied other experiments in what he calls "non-leadership" - commends the model.

"This is the most extreme form I've seen of deliberately moving away from hierarchy," he says.

"What I like most about this is it privileges the idea of dialogue, the idea of collective engagement."

Gabe Newell wanted to create a company without bosses after working at Microsoft for 13 years

He adds that he believes the model works in this case because Valve attracts "elite" performers.

But Mr Powers suggests there's another reason for its success.

"It doesn't work because we have the 1% of the 1%, or however you put that. It works because it was the original philosophy.

"Gabe [Newell] and the crew that started Valve hired people with this in mind.

"That's how we got to a company working effectively for a long period of time under this structure - because it was designed from the beginning."

The firm's stack ranking system is another curiosity.

Staff working on the same project rank each others' technical skills, productivity, team-playing abilities and other contributions.

The information is then used to create an overall leader-board which then helps determine who gets paid what.

The sofas may be static but Valve's desks and chairs are designed to be moved

Although Valve's record suggests the system can work, Prof Oswick warns that it could go awry were the firm to face a financial setback.

"Peer-pressure is a fantastic way of organising a business," he says.

"And so long as everyone is well paid people don't mind being in the bottom earning quartile.

"But as soon as resources become more scarce, then competition increases, which creates conflicts, which creates tensions, which creates hierarchies, which creates concern about relative positioning."

It's something to bear in mind at a time Valve is expected to embark on a potentially costly foray into hardware.

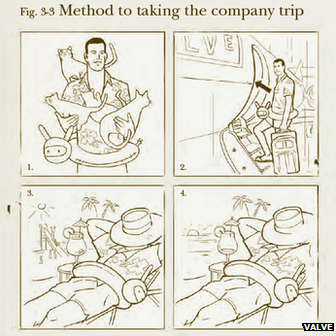

Valve's first "company vacation" was to Mexico in 1998 when it had only 30 employees

In the meantime employees have an expenses-paid week-long holiday to look forward to.

The company regularly flies all 300-plus members of staff and their families to a tropical resort, most recently Hawaii.

The idea of spending free-time with workmates might sound like a nightmare to some, but Mr Powers says it is something that he and the others genuinely look forward to.

"We travel together once a year and it's fun," he says. "Valve's really a family atmosphere in a lot of ways and that gives us an opportunity for our [own] families to get know each other even better."

There are some caveats to Valve's model.

In a land of equals there's recognition that founder Gabe Newell still has most influence.

Or as the handbook puts it: "Of all the people at this company who aren't your boss, Gabe is the MOST not your boss, if you get what we're saying."

And at a firm which says picking who else to hire is its workers' most important task - it describes the activity as "more important than breathing" - there's an acknowledgement that many talented individuals will not fit in.

"The culture is a flat organisation without a lot of top-down direction," explains Mr Powers.

"That's not a comfortable situation for a lot of people."

Valve's handbook declares hiring is "the most important thing in the universe"

Then there's the fact that when a firm without bosses dismisses staff it attracts attention. A decision to let about two dozen workers go in February made headlines across the tech press.

Mr Powers would not discuss the event, but when the Verge news site interviewed, external two of the laid-off employees they appeared to still be on good terms with the company, revealing they had been allowed to retain the intellectual rights to the project they had been working on.

Many gamers wish Valve's employees would decide to release a new game in the Half-Life series

Other companies might blanche at such ideas - and Mr Powers acknowledges it would be a bad idea to retrofit Valve's model to existing businesses - but he indicates there are lessons for start-ups.

"I think the fact that we're not managed by people and we're not managing people and you're able to formulate your own ideas and work with whoever it is to come up with a project or feature - that's empowering," he says.

"It's a community of respect and the best idea wins no matter who it comes from, whether they've been at Valve for a year or founded Valve."

- Published23 September 2013

- Published12 September 2013

- Published12 August 2013