How the Raspberry Pi powers big and small projects

- Published

The BBC's Rory Cellan-Jones finds out how to make a Raspberry Pi

There's no doubt that the Raspberry Pi bare-bones computer has captured the imagination of makers, hackers and artists around the world.

The computers have been put to some novel uses, including a controller for a robot boat that is piloting itself across the Atlantic Ocean.

As the millionth Raspberry Pi rolls off its UK production line, the BBC takes a look at a few of the more ambitious and creative projects that the bare-bones computer has made possible.

Fire Hero - Chris Marion

A bigger, more spectacular Fire Hero is being planned by pyrotechnician Chris Marion

Created by US teenager Chris Marion, external, Fire Hero mates the Raspberry Pi with canisters of propane and a microcontroller to add pyrotechnic effects that synchronise to music being played on an electric guitar.

Hit the right notes and flames will shoot from a rig of six small propane "poofers", four medium-sized "poofers" and two huge cannons.

The big ones produce flames that shoot more than 30m (100ft) into the air.

Mr Marion said work on the original Fire Hero began in 2010, but the Pi helped him refine his control of the flames.

The Pi sits at the centre of the system, reading data from the guitar and passing it to a separate device that opens and closes valves releasing the propane that is then ignited.

Programming the Pi to act as the controller was not the hardest part of the project, he told the BBC.

"The real programming magic lies in the intelligent note and chord detection algorithms to transfer the data stream from the instruments to the Fire Hero device," he said.

Fire Hero 3 has been shown off at a few music festivals in the US and its success has led Mr Marion to plan a bigger, flamier set up that, he estimates, will be six times the size of the latest version.

It will still have a Pi at its core and is set to debut at a festival in 2014.

"My vision is to be able to bring a revolutionary new kind of special effects to live performances that enthrals the audience and provides additional sensory stimulation to further immerse them in the performance," he said.

Treats for Judd - John Saunders

The machine dispensed doggy treats when an email was sent to a specific address

The Pi is not just helping people, man's best friends are benefiting too.

In particular, a Hungarian vizsla dog called Judd has done very well thanks to a Pi-controlled treat dispenser, external.

Created by Judd's owner, John Saunders, the little web-connected gadget dispenses doggy treats when an email is sent to a specific address.

The dispenser drew on many of Mr Saunders's skills, but as he was weakest at coding, getting the Pi to co-ordinate all the moving parts had been tricky, he said.

"I'm not a programmer by trade, so that was much harder for me than the machining and design," he said.

At the time the project was being developed, there was little information or code examples online to help get the gadget working. A web-based appeal helped him debug his code.

The Pi was essential to the interactive part of the treat dispenser, he said. Rival controllers, such as the Arduino, were just as good at connecting to electronics but the Pi was much better when it came to working with the web.

"The machine received so many emails (including corresponding "thank you" emails) that Google shut down the account due to spam-suspicion - so that was frustrating," he added.

Judd liked it too.

"The servo motor does a 'wiggle' upon receiving an email (which happens a few seconds before the treats fall out)," Mr Saunders told the BBC. "Judd learned to recognise this servo noise just about anywhere in the house and would run over to the machine."

Iridis Pi supercomputer - Simon Cox

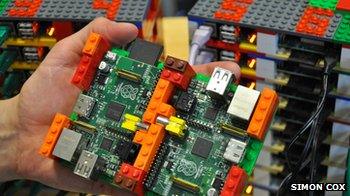

Lego was used as a chassis to hold all the machines that make up the "super-Pi-puter"

Most Pi projects just use one of the machines as a central controller. But one was nowhere near enough for Simon Cox, an engineering professor at the University of Southampton.

Prof Cox created a supercomputer for less than £2,500 using 64 interconnected Raspberry Pi devices. The computing cluster runs off mains power and can address 1TB of memory.

"Building it was absolutely not about computer power," he said. Instead the system, dubbed Iridis Pi, was built to help people get to grips with the computational challenges of working with large numbers of tightly connected computers.

"It's about understanding all the pain of getting them to work together and the intricacies of building an algorithm to use them," he said.

That was a skill all engineers needed in order to design and test their ideas, he said, but one that few had a chance to exercise before they reached university.

The schematics and software for Iridis-Pi had been publicly released so anyone could replicate it and start developing that much-needed competence with computational science, said Prof Cox.

The Beet Box - Scott Garner

The Beet Box makes a virtue of hiding the Pi at its heart

Most Pi-based projects flaunt their wires and make a virtue of the tiny computer at their heart. Not so with Scott Garner's Beet Box project.

In the creation of these interactive vegetables, Mr Garner, a designer and craftsman, was more interested in what he calls "invisible technology".

"I like the idea of the next generation growing up in a world that isn't all screens and buttons - I think some nice wood and a few vegetables make for a good alternative," he said.

"Having done some experiments with both capacitive sensors and 'edible circuits', I decided it would be interesting to combine both concepts," he added.

"I spent a little time trying to think of the perfect vegetable-instrument combo and once I hit on beats from beets there was no looking back."

The Pi won out over other ways to connect up and control sensors and speakers because of its processing power. Despite its flexibility this Pi project did present some unique problems.

"Dealing with produce as part of a circuit definitely comes with some challenges," said Mr Garner.

"The biggest difficultly is that as the beets dry out, their ability to conduct the touch signals is weakened.

"In practice, though, they suffered cosmetic damage from so many hands long before they failed as sensors, so having a few spares at the ready was necessary."

CreepyDol - Brendan O'Connor

Pi-powered passive sensor networks could help keep an eye on endangered species

The Raspberry Pi computers that Brendan O'Connor has used for his project are also hidden, albeit for very different reasons.

Mr O'Connor has used the devices to help create some passive surveillance devices that can sit and sip the air for all the data leaking out from smartphones, tablets and laptops.

Mr O'Connor's plan was to spread a series of the Pi-powered sensors, or Distributed Object Locators (Dols), around a city and use them to gradually build up information about the gadgets that pass by.

Each one is about the size of a can of spam and is battery powered so it could sit unobtrusively in a locker, on top of a cupboard or in a bush in a park for weeks grabbing data.

The Pi helped make it possible to get the boxes co-ordinating the information they find and sending it to their controller.

The boxes - called CreepyDols - gather up the many status and query messages sent out by the gadgets that people carry around, said Mr O'Connor.

Most of them had no idea their gadgets were broadcasting this information or that it could be used to pick them out of a crowd.

"Even a very savvy user has no way to stop it being shared," he said.

Passive surveillance systems were also finding a role in environmental monitoring, said Mr O'Connor, where many different local conditions, such as humidity, temperature and rainfall, needed to be logged over a long period of time.

- Published9 September 2013

- Published3 October 2013

- Published26 August 2013

- Published20 March 2013

- Published6 June 2013