Edward Snowden revelations: Can we trust the spying state?

- Published

Gordon Corera reports on the true scale of the NSA surveillance system revealed by Edward Snowden and how worried we should be.

How worried should we be by the state's capability to spy on us?

Top secret documents, leaked by former American intelligence contractor Edward Snowden, have revealed the huge capacity of Britain and America's intelligence agencies - GCHQ and the NSA - to capture communications.

Snowden and his supporters have argued that the public should know more about what is happening, while governments have argued that exposure has endangered national security.

Four months after the first revelations in the Guardian newspaper, a picture has emerged of Britain and America's intelligence-gathering capabilities.

Taken together, the reports point to an ambition to be able to reach into the vast global tide of digital communications and be able to pick out any message and read it, as well as to conduct wide-ranging searches of billions of records to look for patterns and connections.

"Even if you're not doing anything wrong you're being watched and recorded," argued Edward Snowden. "You should decide if they should be doing this."

Those who have worked inside the secret state say that the power is vital for national security and only used for national security.

"You have to have a powerful capability to find the small amount you're looking for - but that doesn't mean the state is reading everyone's emails," former GCHQ director Sir David Omand told the BBC.

"What the state needs and law enforcement needs is the possibility of accessing the communications of the terrorists, the criminals, the kidnappers, the proliferators, the paedophiles. But those communications are all mixed up with everyone else's communications - there are 204 million emails a minute buzzing around the globe.

"So you have to have a powerful capability to find the small amount that you are looking for. But it doesn't mean that the state is reading everyone's emails, nor would that conceivably be feasible."

'Age problem'

But can we trust the state with this power?

Technology allows it to do things it could never have done before - collecting and sifting through billions of records using data mining to find a connection or reconstructing a person's social interactions from the trail they leave behind online.

The lack of sufficient oversight worries those who have campaigned on civil liberties.

"Part of the problem here is an age problem," says David Davis, a former Conservative Shadow Home Secretary.

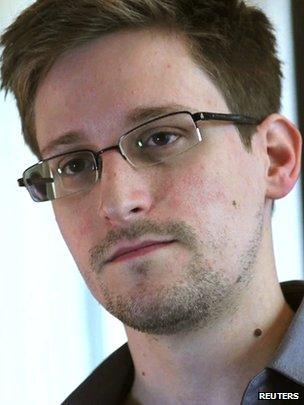

Edward Snowden fled to Russia after publicising the actions of the US National Security Agency

"My generation of politicians - up to ones 20 years younger than me - don't really understand the extent to which we are intruding into people's privacy."

Mr Davis believes the current system of oversight and accountability is not strong enough, especially when access to metadata about communications and interactions only requires internal authorisation within an intelligence agency - and not the warrant that is required to intercept the actual content of communications.

"There is no need to trust the state unless it has got a good reason and they must justify that to someone else - a judge or a magistrate or someone who is outside their system and can check they are using it properly," he argues.

The claim that encryption standards have been deliberately weakened or had so-called "backdoors" added to allow access by intelligence agencies caused particular anger among those who have spent their careers trying to improve internet security and ensure the privacy of communications.

"The NSA's actions have done more than undermine online security - they've threatened to break the internet," Ross Anderson, Professor in Security Engineering at Cambridge University says of its attempts to ensure access.

"In order to do this they have compromised in various ways the protocols on which the internet relies. When you introduce these vulnerabilities, they are not just for the spies to use. They are available for bad guys to use as well."

Spook heyday

The Snowden documents have surprised many, including Prof Anderson, in terms of the scale of what they reveal.

"To find that they had built this machine and got it working is an eye-opener," he told the BBC.

Critics of the intelligence agencies believe the disclosures have been important in starting a public debate about whether we know enough about the state's capability and whether there are enough controls and oversight.

But many of those inside the intelligence world point to the damage which they say the revelations have done. They fear that since Edward Snowden is in Russia, the Russian state will have found some way of accessing the information.

"Part of me says that not even the KGB in its heyday of Philby, Burgess and Maclean in the 1950s could have dreamt of acquiring 58,000 highly classified intelligence documents," Sir David Omand told the BBC.

The concern is also that the more that is revealed in public, the more the targets of surveillance adapt their behaviour. Sir David believes Snowden's actions will do real damage to national security.

"My fear is that we are now going to witness a slow-motion car crash in which gradually sources dry up, targets such as terrorists and cybercriminals will work out what are the kind of capabilities we have, and they will adopt their methods and be harder to track down," says the former GCHQ director.

In the last week, the BBC was given direct access to a small selection of original documents held outside the UK that form the basis of stories the Guardian newspaper has already published.

The scale of the capability they reveal - and the secrets they contain - make clear there are serious issues involved in balancing the public interest and national security. That balance lies at the heart of this debate - between the public interest and the right to know about what the state can do and the need for the state to protect its secrets and its capabilities for the sake of national security.

The question remains - who gets to decide?

- Published1 October 2013

- Published16 December 2013