How the modern world depends on encryption

- Published

Encryption helps to ensure that credit card transactions stay secure

Encryption makes the modern world go round. Every time you make a mobile phone call, buy something with a credit card in a shop or on the web, or even get cash from an ATM, encryption bestows upon that transaction the confidentiality and security to make it possible.

"If you consider electronic transactions and online payments, all those would not be possible without encryption," said Dr Mark Manulis, a senior lecturer in cryptography at the University of Surrey.

At its simplest encryption is all about transforming intelligible numbers or text, sounds and images into a stream of nonsense.

There are many, many ways to perform that transformation, some straightforward and some very complex. Most involve swapping letters for numbers and use maths to do the transformation. However, no matter which method is used the resulting scrambled data stream should give no hints about how it was encrypted.

During World War II, the Allies scored some notable victories against the Germans because their encryption systems did not sufficiently scramble messages. Rigorous mathematical analysis by Allied code crackers laid bare patterns hidden within the messages and used them to recreate the machine used to encrypt them.

Those codes revolved around the use of secret keys that were shared among those who needed to communicate securely. These are known as symmetric encryption systems and have a weakness in that everyone involved has to possess the same set of secret keys.

In the modern era, a need has arisen to communicate securely with people and organisations we do not know and with whom we cannot easily share secret keys, said Dr Manulis. This need has given rise to public-key cryptography. Despite the formidable name it encapsulates a simple idea.

Wartime code-cracking machines such as Colossus broke German encryption systems

Essentially, it allows anyone to send a message that only one person (or company or website or gadget) can unlock. It does this using two keys: one public, one private. The public key is used to lock a message. Anyone can get hold of that public key but once a message is locked with it, that message can only be opened with the corresponding private key.

Typically these keys are large numbers and the security of the system depends on the fact that some mathematical operations are easier than others.

For instance, it is far easier to multiply numbers together (public key and plain text message) to get a result than it is to start with that result (the scrambled message) and work backwards. Complicated mathematics guarantees that the right private key will unscramble a message.

Far harder, even for the fastest computer, is starting with that result (the scrambled message) and searching through all the possible combinations of numbers that could produce it.

"Because of the size of the keys is so huge its impossible for an attacker to search through the key space with the resources they usually have," he said. Such "brute force" attacks are pretty much doomed no matter how much computer power attackers bring to bear, he said

Typically the numbers used in these mathematical encryption systems are tens if not hundreds of digits long. This makes it impossible, to all intents and purposes, to search through all potential keys in a reasonable amount of time.

The web and many other modern communication systems employ a hybrid approach, said Dr Manulis, because public key encryption is not very computationally efficient compared to symmetric key encryption.

Even supercomputers would not break the strongest encryption algorithms

On the web, the relatively slower public key cryptography is used initially to establish a secure connection between you and a website. The symmetric system would be no good for this step because there is no way to securely swap the secret key.

However, with a secure channel in place, the faster symmetric system can be used to share a key and then scramble the data passing back and forth.

On mobiles, a similar system is used and encryption keys are held on a handset's sim card to help keep chatter scrambled.

Vulnerabilities

Attacks on these encryption systems take many forms, said Dr Manulis.

"You do not need to break the communication system if you have some spy software on the end point," he said.

In addition, weaknesses have been found in the software used to encapsulate them on computers and phones.

"The algorithms are mathematically proven," he said, " and if there's any problem then it usually comes in the implementation of the algorithm."

In addition, there have been suggestions that the NSA has subverted the process of creating encryption algorithms, to make them easier for it to break.

Official agencies can also force firms, be they websites or mobile operators, to surrender their private keys so they can eavesdrop on supposedly secure communications.

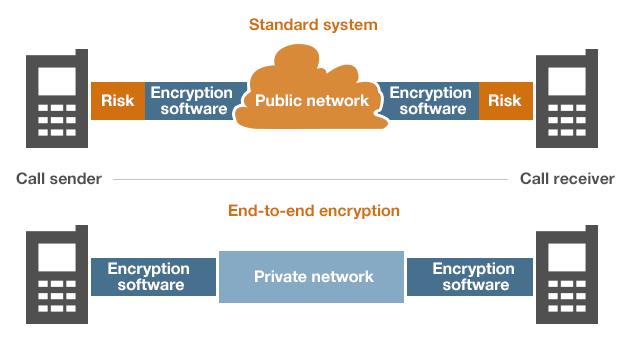

Some have sought to get make encryption more secure by using a technique known as end-to-end encryption.

This differs from more standard systems which can be vulnerable because their scrambling system is, in software terms, separate from the program used to create a message.

If attackers insert themselves between the message making software and the encryption system at either end of a conversation they will see information before it is scrambled.

End-to-end encryption closes this gap by having the message making software apply the scrambling directly. In addition, many of these systems run a closed network so messages never travel over the public internet and are only decrypted when they reach their intended recipient.

Some fear that sending data over public networks makes it more susceptible to surveillance