Could hi-tech accessories make cycling safer?

- Published

Emily Brooke is hoping to save lives with her laser-based bicycle light

Although more people are getting around by bike, cyclists remain the most vulnerable group of road users. Could a range of wearable technologies keep them safer?

In the UK, the number of people killed in cycling accidents is on the rise.

Most serious incidents involve another vehicle and commonly occur when the cyclist is travelling straight ahead and another vehicle turns into it, research suggests, external.

That's why Emily Brooke, founder of Blaze, says she designed a light that projects an image of a green bike onto the ground about 5 metres (16ft) ahead of the cyclist.

'Lit like a Christmas tree'

Blaze uses a laser to project the bike symbol on the ground. It is also fully waterproof and comes in a sleek aluminium case with a backlit control panel.

"It's vehicles travelling in the same direction as you that cross your path who would see this light," Ms Brooke says. "This helps in your classic blind-spot scenario.

Blaze projects an image of a bicycle onto the road ahead to alert drivers

"You can be lit up like a Christmas tree and have every light on the market, but ultimately if you're in the vehicle's blind spot, you're still invisible."

"They see this light and don't turn."

At FlyKly, which makes electrically-assisted bike wheels, Niko Klansek says safety concerns are a key reason why people choose not to cycle.

During a campaign on crowdfunding site Kickstarter to raise cash for the "smartwheel", many people asked for it to be available in fluorescent colours so that they could be seen more easily from the side.

"Otherwise the usual lights are just at the front and back," Mr Klansek says. "But it's really important to be seen from the side too."

'Outstanding design flaw'

Cycling safety expert Ian Walker, of the University of Bath, agrees, saying anything cyclists can do to make themselves more visible to drivers - such as wearing reflectives and lights, especially in the dark - is an advantage for them.

But former professional cyclist Michael Hutchinson says many people do not use safety equipment because they do not like the look of it.

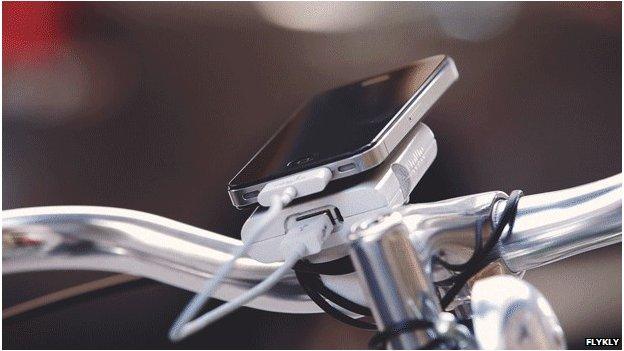

The Flykly stand doubles up as a light and a charging terminal

"The most outstanding design flaw with the traditional polystyrene helmet is that it messes up people's hair, it's sweaty on the head," Mr Hutchinson says.

"Also a lot of people don't like the look of bike helmets."

Niko Klansek, of FlyKly, agrees, saying that if people could cycle without breaking a sweat many more would use one to get to work.

"They want to dress for their destination, not for the bike ride," Mr Klansek says of his customers.

'Invisible' helmet

Anna Haupt, co-founder of Hovding, says she encountered the same sort of resistance to wearing helmets.

"People told us they wanted an 'invisible' cycle helmet," she says.

"We heard it over and over again, that people did not want to wear helmets because it ruined their hair."

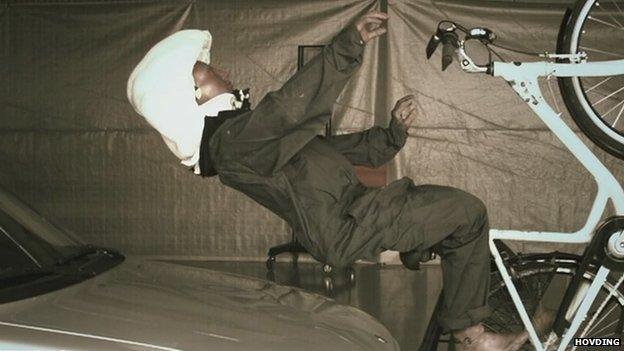

The Hovding airbag helmet takes one eighth of a second to release

Hovding's airbag-style head gear stays folded inside a neck collar until the moment it detects an accident taking place.

Once the collar is switched on it uses six sensors to monitor the body's movements 200 times per second, registering both the angles and speed of the neck.

During the ride, the helmet keeps track of the readings - ready to release the airbag if it receives a single data point that falls outside the normal range.

"If you happen to be in an accident, your body movements will be completely different from normal cycling," Ms Haupt explains.

The Hovding helmet sits around the neck until it detects an accident and releases the airbag

The helmet has been tested extensively so it does not inflate because of another sudden action

The Blaze bike light is designed to alert drivers to a cyclist's presence so the car does not turn into the bike

The Blaze light has a magnet that detects when it is on the handlebars. Only then can the laser be used

The Flykly wheel can be fitted to all sorts of bikes

"An icy road produces more angular adjustments, and if you get hit by a car it's a very obvious acceleration in your body," she says.

But Dr Ian Walker says it isn't only cyclists that have a mental block about helmets.

While they are an important protection if an accident takes place, seeing bikers wearing a helmet can actually cause some motorists to drive less carefully around them, he says.

Reflexes 'too slow'

Ulf Bjornstig, Professor of Surgery at Umea University, says that in Sweden cyclists are in more accidents than any other type of road user.

Head injuries are the most common, with 10% of victims suffering concussion or becoming unconscious, he says.

"The head hits the ground quite hard. If we look at non-fatal injuries, quite often you land on the ground with your face - nose, chin."

But in the case of fatal accidents, "those victims are often hit from behind or the side," Prof Bjornstig says.

"That's the difference between fatal and non-fatal injuries."

Jurij Lozic, in Slovenia, who recently completed a Kickstarter campaign for a bendy mudguard originally designed for fixed-gear bikes, says style and aesthetics are very important in making a product sell.

His Musguard fenders are die cut from recyclable polypropylene - a common kind of plastic sheeting - and come in a range of bright colours.

Musguard's fender was designed for minimal cycles that do not come with their own

"People want beautiful products to enhance their bikes," Mr Lozic explains.

Preventing future accidents?

But as appealing as some accessories may be, former professional cyclist Michael Hutchinson is sceptical that the average biker would be willing to spend large sums solving the problem.

The Hovding helmet costs nearly 400 euros (£330) while the Blaze bike light can be pre-ordered for £125.

Mr Hutchinson adds that he fears accessories such as helmets are something of a "distraction" in the bigger picture of improving cyclist safety.

"At a fundamental level, helmets will not prevent a single accident," he says.

Dr Ian Walker agrees, saying that when it comes to preventing accidents, "nothing is going to get safer than hard segregation of cyclists and motorists".

- Published20 November 2013

- Published19 November 2013

- Published8 November 2013

- Published15 November 2013