How to make money finding bugs in software

- Published

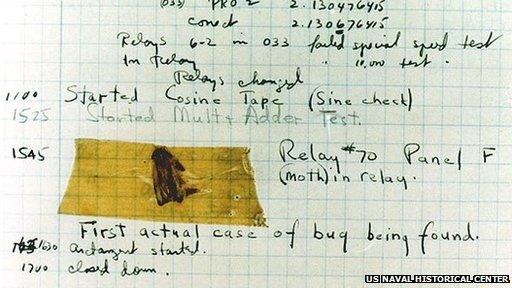

The first computer bug was an actual insect - a moth caught in the Harvard Mark II's hardware

The first computer bug was found in 1947 when a moth got caught in one of the relays of the Harvard Mark II.

Computers have changed a lot in the 67 years since that dead insect was pulled from a relay's jaws but bugs can still trip up a machine.

The bad news is that in these days of rampant cybercrime, they can give attackers an easy way in to a target machine. The good news is that finding bugs can be lucrative for the good guys too.

Big bugs are usually found as programs are readied for release. However, the number of experts software makers can call on to check for the types of bugs that cyberthieves prefer is limited, even for the biggest companies.

Small wonder then that more and more software makers are running bug bounty programmes that reward people, usually independent security researchers, who can spot bugs and other vulnerabilities for them.

The bounty might be a T-shirt or free software, or sometimes a laptop. But increasingly, says Casey Ellis, who founded and oversees the Bugcrowd web community, the rewards are cold, hard cash.

"As soon as you introduce that kind of incentive you engage more testers and you engage a better quality of researcher," he said. "Everyone should have a bug bounty programme of some sort."

Bugcrowd is 6,000 members strong and it acts as a hub for bug finders and companies that need bugs to be found. It lists bounty programmes and rewards and helps to standardise the ways bugs are reported.

Logic look

So who are the bug finders?

"There are two distinct groups of testers," said Mr Ellis. "There are ones that focus on finding issues using a very technical approach and then there are those that try to think like the bad guys."

James Forshaw from security firm Context sits firmly in the technical camp.

"I specialise in finding logical errors," he said. "That's not about exploiting a piece of code but a whole chain of logical operations so you get a result you did not expect."

Mr Forshaw found a bug that got round security built in to Windows 8

This can involve painstaking work to trace the way processes and functions interact in software. It can be especially hard with Microsoft products because relatively little of its core source code is available. Instead, security engineers like Mr Forshaw use tools that work on an abstracted version of that underlying computer code.

Sometimes the end result of all the careful analysis is nothing. And sometimes he hits pay dirt.

In October last year, Mr Forshaw was rewarded with a $100,000 (£60,000) bug bounty from Microsoft for finding a deep bug in Windows 8.1 that, if exploited, would have allowed attackers to bypass the novel protection systems built in to it.

"The day I found that was a pretty good day," he told the BBC.

But he acknowledged that his approach drew on his extensive experience built up since he got his first computer at the age of six and after which he became a dedicated code junkie.

Many other bug finders have used their skill to cash in. This is because software companies are not the only ones paying to hear about bugs. Cyber-thieves have put up cash pools for vulnerabilities they can exploit with viruses and other malicious programs.

But the biggest buyers of bug reports are governments - and the potential rewards are huge. Papers released by whistle-blower Edward Snowden suggest the US National Security Agency spent $25m a year buying bugs. Companies have emerged that act as brokers between researchers and buyers and there are anecdotal reports of people getting rich on the back of these deals.

Quick start

So is there any hope for those already older than six who do not have a deep technical knowledge of software? Can anyone get involved?

Yes, says Casey Ellis from Bugcrowd, adding that many of its testers started out as teenage novices but are now doing well. There are others too.

"I started at the age of 14 with searching simple web-application vulnerabilities," said German teenager Robert Kugler, who is now 17. "Security was always a fascinating topic for me, so I taught myself information security basics and studied further."

Since then he has managed to find bugs for Mozilla, Avast, PayPal, Yahoo, Microsoft, the Dutch government and Belgium's military intelligence service. He's netted about $5,000 for his trouble.

Finding a bug on Facebook took persistence and time

But he admits that it is not easy.

"You need to have a good analytical ability and you need to be able to understand the coherencies," he said. "Last but not least, patience and creativity are very important skills."

Another example of how straightforward it is comes from Chris Wysopal - a former member of the notorious Lopht hacking group. In May 1998, the group testified before the US Congress that they could shut down the internet in 30 minutes.

Mr Wysopal now helps run security company Veracode, producing automated tools that look for bugs and other coding glitches.

Those tools can find code that is vulnerable to well-known attacks or highlight places where its use of some security features, such as cryptography, are weak. Going beyond that requires people who can take a higher level view of how code fits together, said Mr Wysopal.

But, he said, those people do not necessarily need technical skill.

Mr Wysopal's daughter Renee netted a $2,500 bounty from Facebook for discovering that its privacy module sometimes failed to block others from seeing your pages.

Despite being an arts graduate, Ms Wysopal found the bug after getting guidance from her dad about how to view a webpage's source code and using a proxy to change the data passed to it.

"I told her how to focus on complex and new functionality as that might have more security bugs," he said.

Finding the bug took a few days but by the end of that she had found a way to ensure supposedly blocked messages could get through to a person's page.

Her experience was unlikely to be unique, said Mr Wysopal.

"I don't think it is that hard to find bugs in many products," he said. "You just have to look."

- Published2 January 2014

- Published29 November 2013

- Published11 December 2013