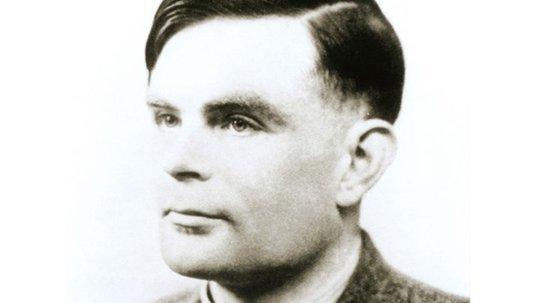

Royal pardon for codebreaker Alan Turing

- Published

- comments

Computer pioneer and codebreaker Alan Turing has been given a posthumous royal pardon, as Danny Shaw reports

Computer pioneer and codebreaker Alan Turing has been given a posthumous royal pardon.

It addresses his 1952 conviction for gross indecency following which he was chemically castrated.

He had been arrested after having an affair with a 19-year-old Manchester man.

The conviction meant he lost his security clearance and had to stop the code-cracking work that had proved vital to the Allies in World War Two.

The pardon was granted under the Royal Prerogative of Mercy after a request by Justice Minister Chris Grayling.

'Appalling' treatment

"Dr Alan Turing was an exceptional man with a brilliant mind," said Mr Grayling.

He said the research Turing carried out during the war at Bletchley Park undoubtedly shortened the conflict and saved thousands of lives.

Turing's work helped accelerate Allied efforts to read German Naval messages enciphered with the Enigma machine. He also contributed some more fundamental work on codebreaking that was only released to public scrutiny in April 2012.

"His later life was overshadowed by his conviction for homosexual activity, a sentence we would now consider unjust and discriminatory and which has now been repealed," said Mr Grayling.

"Turing deserves to be remembered and recognised for his fantastic contribution to the war effort and his legacy to science. A pardon from the Queen is a fitting tribute to an exceptional man."

The pardon comes into effect on 24 December.

Turing died in June 1954 from cyanide poisoning and an inquest decided that he had committed suicide. However, biographers, friends and other students of his life dispute the finding and suggest his death was an accident.

Many people have campaigned for years to win a pardon for Turing.

Author Barry Cooper: Turing "created blueprint for computer"

Dr Sue Black, a computer scientist, was one of the key figures in the campaign.

She told the BBC that she hoped all the men convicted under the anti-homosexuality law would now be pardoned.

"This is one small step on the way to making some real positive change happen to all the people that were convicted," she said.

"It's a disgrace that so many people were treated so disrespectfully."

Some have criticised the action for not going far enough and, 59 years after Turing's death, little more than a token gesture.

"I just think it's ridiculous, frankly," British home computing pioneer Sir Clive Sinclair told the BBC.

"He's been dead these many years so what's the point? It's a silly nonsense.

"He was such a fine, great man, and what was done was appalling of course. It makes no sense to me, because what's done is done."

'It's very wrong'

Lord Sharkey, a Liberal Democrat peer who wrote a private member's bill calling for a royal pardon in July 2012, said the decision was "wonderful news".

Turing memorial sculptor: "What about all the other thousands of gay men who were prosecuted?"

"This has demonstrated wisdom and compassion," he said. "It has recognised a very great British hero and made some amends for the cruelty and injustice with which Turing was treated."

Vint Cerf, the computer scientist known as one of the founding fathers of the internet, also welcomed the development.

"The royal pardon for Alan Turing rights a long-standing wrong and properly honours a man whose imagination and intellect made him legendary in our field," he told the BBC.

Technology entrepreneur Mike Lynch added: "Society didn't understand Alan Turing or his ideas on many levels but that was a reflection on us, not on him - and it has taken us 60 years to catch up."

Human rights campaigner Peter Tatchell said: "I pay tribute to the government for ensuring Alan Turing has a royal pardon at last but I do think it's very wrong that other men convicted of exactly the same offence are not even being given an apology, let alone a royal pardon.

"We're talking about at least 50,000 other men who were convicted of the same offence, of so-called gross indecency, which is simply a sexual act between men with consent."

Mr Tatchell said he would like to see Turing's death fully investigated.

"While I have no evidence that he was murdered, I do think we need to explore the possibility that he may have been killed by the security services. He was regarded as a high security risk," he said.

'Not entirely comfortable'

Glyn Hughes, the sculptor of the Alan Turing Memorial in Manchester, said it was "very gratifying" that he had finally been pardoned.

"When we set out to try and make him famous - get him recognised - it was really difficult to collect money," he said.

"None of the big computer companies would stump up a penny for a memorial. They perhaps would now - we've come a very long way."

But he said he was "not entirely comfortable" that Turing had been pardoned while thousands of other gay men had not.

"The problem is, of course, if there was a general pardon for men who had been prosecuted for homosexuality, many of them are still alive and they could get compensation."

In December 2011, an e-petition was created on the Direct Gov site that asked for Turing to be pardoned. It received more than 34,000 signatures but its request was denied by the then justice secretary, Lord McNally, who said Turing was "properly convicted" for what was at the time a criminal offence.

Prior to that in August 2009, a petition was started to request a pardon. It won an official apology from the prime minister at the time, Gordon Brown, who said the way Turing was persecuted over his homosexuality was "appalling".

- Published24 December 2013

- Published3 October 2013

- Published22 June 2012

- Published22 June 2012

- Published8 March 2012