2014: the year of the smarter watch?

- Published

The BBC's North America Technology Correspondent thinks 2014's wearable tech needs to get a lot smarter if it is to go mainstream.

"Welcome to the future!" exclaims the Pebble app on my phone, moments after I unsheath the monochrome plastic smartwatch itself from the eco-friendly packaging.

Really? I don't know about you, but I've always envisioned my hi-tech wristwatch glowing in full technicolour, a sleek, highly-contoured design statement, perhaps; most certainly not a 1.2in (3cm) bulky plastic-coated non-touchscreen, emitting 256 shades of grey.

Sporting all the futuristic looks of a Palm Pilot circa 1999, the Pebble is a time-travelling companion I can easily envisage my future without.

That's not to say it doesn't have virtues over the competition.

After all, the Pebble has chosen the eminently sensible route of a low-power display helping its battery last more than a day or two without recharging - almost a week, in fact.

It stays focussed on its singular purpose in life - to present notifications from your smartphone, which you can now keep tucked away in a jeans pocket. And priced at under $200 (£122), some of its hyperbolic claims are a little more forgivable.

Pebble watches communicate with their owners' smartphones via Bluetooth

That's more than can be said of its rivals. For example, Samsung's smartwatch, Gear, certainly boasts a more grandiose air, with pretensions and a price point to match: $300.

It's definitely more attractive, and impresses with a sharp colour display. But its kitchen-sink approach lets it down.

It'll let you know an email has arrived - but you have to pull out one of only three high-end compatible handsets to actually read it.

Hmm. Fancy mimicking Inspector Gadget?

The Galaxy Gear has a 1.9 megapixel camera built into its wrist strap

Well, now you can, taking snaps and short video clips directly from the Gear's sub two-megapixel snapper and make calls from your wrist - neither of which which you're likely to do with any regularity.

All of this comes at the expense of frequent battery charging - for which you need to encase it in in a charging cradle.

Ahead of their time

On the surface the problem with wearables - and smartwatches in particular - is that the technology just isn't mature enough to support the ambitions.

Screen resolutions may have improved, processors made more efficient and sensors miniaturised, but it's still hugely challenging technically to squeeze everything into a surface area the size of a watch face - and to keep it all going for any reasonable length of time.

More fundamentally though, many of the botched smartwatch attempts to date are symptomatic of deeper dynamics at play in the technology world.

This is an industry desperate to sell us "the next big thing" - and it sees our wrist, eyes and other parts of our anatomy - smart rings, anyone? - as ripe for the picking now that smartphones are maturing and tablets are becoming commoditised

There are also engineering-led cultural forces to contend with.

All- too-often the technologists are allowed to overindulge.

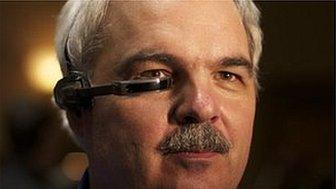

Vuzix beat Google Glass to get its eyewear to market, but how many people want to look like this?

Half-baked products are rushed out and propagated by marketeers extolling them as lifestyle-enhancing in ways we never even imagined.

In a more design-led culture the user would be the starting point, not the goal - a precept frequently ignored.

Wearing technology is a huge statement - and one which transcends fashion.

Robert Brunner, founder of Ammunition Group's design lab - whose work includes Beats by Dre - notes that it conveys the tribe you belong to, or aspire to belong to.

"Unless people are comfortable or even motivated to wear it, it's not going to go anywhere," he tells me.

"Bluetooth headsets were associated with limo drivers and salespeople - and that put boundaries around the product."

Limited ambitions

If our wrist presents a subtle expression of that notion, then asking non-glasses wearers to adorn the most visible part of their personal real estate with eyewear just compounds the issue. Especially if it doesn't have a compelling use-case.

I wonder if barcode scanning and news alerts fall into that category?

Jawbone Up does not have a display of its own, but provides feedback via a smartphone

Nike's Fuelband, Jawbone Up, Fitbit Force and other standalone wrist-borne devices excel in one department - the so-called Quantified Self - providing useful data about exercise, sleep and other health metrics.

Fitbit's co-founder James Parks tells me the company can explain its success on staying singularly focussed on an addressable need.

"The problem with smartwatches is figuring out what they're good for", he says.

"When you try to do everything, you end up not doing any one particular thing very well. "

So what can the industry deliver in 2014?

Clearly it needs technological advances - like longer battery life combined with less power-hungry displays.

Some improvements are still tantalisingly out of reach: wireless charging, an idea already integrated into a smartwatch from start-up Agent, is a neat idea to make recharging easier. But charging surfaces need to be integrated into more surfaces around us.

Flexible OLED displays are too expensive. Most importantly of all, these gadgets need to be desirable - good-looking and really, really, useful if we're to replace our watch or suddenly start wearing glasses.

The crowdfunded Agent smartwatch promises to allow wireless charging

Smartwatches are not without merit in principle - even today.

There's scope even for the current crop of devices to improve significantly with decent software updates.

With clever design and a focus on usability, they could save us the aggravation of pulling out and unlocking our smartphones, potentially providing a friction-free way of getting tidbits of information as and when we need it.

These are the days of Wearables v1.1, the industry experimenting, iterating and learning as it goes.

That's fine - for the early adopter set.

In a few years we'll get there, I've little doubt. But we're not there yet. So there's no point pretending we're anywhere close - let alone time-travelling merrily into the future.

Follow Richard Taylor on Twitter @RichTaylorBBC, external

- Published24 December 2013

- Published2 December 2013

- Published16 October 2013

- Published5 September 2013

- Published4 June 2013

- Published9 January 2013