Apple Mac development team reunited 30 years on

- Published

Members of the Apple Macintosh design team reminisce about the launch

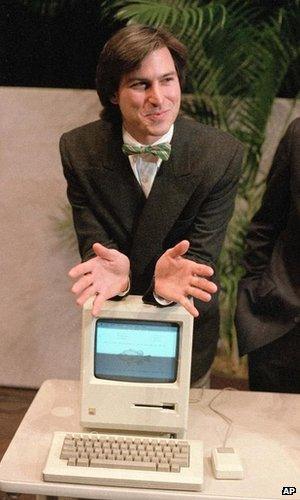

It's hard to imagine nowadays, but when Apple introduced the Macintosh personal computer in 1984 it was widely dismissed as a "toy".

Others called the Mac "just a demo - not a real computer yet," Randy Wigginton, creator of the Mac's first word processor, tells the BBC.

"We didn't have all the software that the IBM PC had or even that the Apple II had," he says.

"It was slow. There were things that it didn't do well."

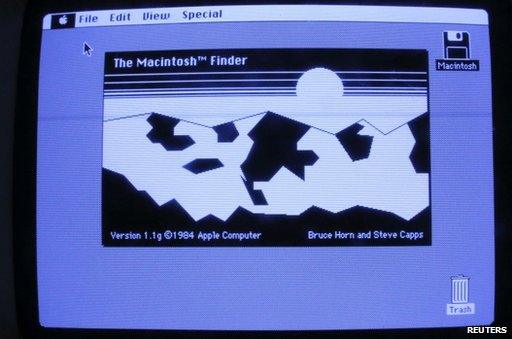

Back then, programmers also thought it absurd the Mac designers had abandoned the typical alpha-numeric interface in favour of a friendlier graphical one and a point-and-click mouse, making it too easy for users, recalls Leander Kahney, editor of The Cult of Mac news website.

"They thought it trivialised their profession," he adds.

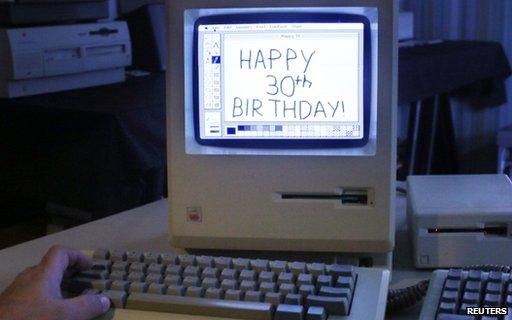

The surviving members of the Mac development team reunited to mark its 30th birthday

The original model's 128 kilobytes of RAM (random access memory) also limited its use.

But three decades later, Macs are still here and selling briskly.

Over the weekend, more than 100 members of the original Mac team were reunited at the Flint Center in Cupertino, California, where Apple's co-founder Steve Jobs had first introduced the computer on 24 January 1984, to commemorate its 30th anniversary.

Below, in their own words, are excerpts from the pioneering software and hardware developers' recollections of creating the all-in-one computer.

The original Macintosh computers were manufactured without a hard drive

Hardware design

The developers were asked if they had felt defensive about other PC-makers laughing at them for selling a "closed box".

Jerry Manock (industrial design lead):

Steve had an incredibly good answer to that. [When] the Apple II came out, third-party vendors could put boards in, you could use other monitors, etc.

Steve Jobs left Apple one year after unveiling the Macintosh

Whenever there was a failure, or the customer had a problem, Apple Computer got the call.

It could have been [the fault of] any number of third party vendors. It could have been the monitor, the disk drive, whatever.

So, Steve made the decision: if we supply the display and the boards [and] everything is sealed up inside the box and it works when it leaves the factory, then we're willing to take the responsibility of answering the service calls.

Bill Atkinson (developer of MacPaint & MacDraw):

We were trying to make something that was user-friendly and that meant someone could walk up to it and figure out how to use it without using a manual.

Jerry Manock:

Jef Raskin's [original Mac project leader] idea was portability.

When Steve took the Mac project over, he had a vision that this computer was going to be sitting on a worker's desk.

He wanted it to [take] minimal space on the desk, so that was a pretty radical change.

Tough task master

George Crow (analogue circuit board engineer):

We knew if [Steve] just ground you down a few days you'd come up with an even better idea a few days later.

Bill Atkinson:

Steve wasn't really an engineer but he knew how to get the best out of people.

One time Larry Kenyon was working on the operating system, and Steve said: 'We need to make this thing faster, it's taking too long to start up. Now Larry, if it would save someone's life, could you make it 10 seconds faster?'

Larry said: "Yeah, probably I could."

Two days later, it was 30 seconds faster.

The original Mac had only 128K of RAM, which was bumped up to 512K in its successor

Microsoft's role

The team were asked what it was like having Microsoft write some of the application software, knowing that co-founder Bill Gates later remarked he had more people working on the original Mac's software than Apple did.

Randy Wittington (MacWrite developer):

If they had more people than us it doesn't speak very highly of the quality of the piece that they had.

Andy Hertzfeld (Mac operating system developer):

Microsoft wasn't what they became at that time. They were a small private company. Apple probably had 20 times the revenues of Microsoft when they started, but they were our close collaborators.

They were the first company we gave a Mac to. They really helped us.

We didn't have enough applications. We really only had MacPaint and MacWrite, [and] they were working on three applications.

The Mac ran its operating system off a floppy disk, which came with the computer

Pricing controversy

The Mac's early development team envisioned selling the personal computer for $1,000 (£605), but later, after the cost of essential parts like Motorola's 68000 microprocessor were factored in, the price bumped upwards.

Andy Hertzfeld:

$1,495 that was our price for years and years and years.

Then... John Sculley [Apple's chief executive at the time] convinced us we have to charge $2,495 to pay for a big marketing campaign. That kind of broke my heart because that really is the difference of a kid being able to get their hands on one or not.

Caroline Rose (Documentation developer):

I remember the meeting where that price was announced. It was such sad day... We were all just really depressed.

Andy Hertzfeld:

Because we all thought we were making something for ourselves and the people we cared about. And that price, once it got up above $2,000, it could no longer be that.

The Mac helped popularise the idea of a graphical user interface

Passion and invention

Bill Atkinson:

It wasn't work. We were making art. Steve insisted that we sign our names on a piece of paper with a Sharpie [pen] and he engraved it on to the mould [inside of the case of the first production run] so all of our signatures would be on it. And the reason is: real artists sign their work and they're proud of it.

Rod Holt (co-developer Mac Finder):

This process of invention is very unusual... we were more than willing workers.

The peculiar thing was that [Jobs] didn't understand somebody would work day and night on a computer or any other project and not do it out of love.

But, see, we weren't doing it for money. I don't think anybody would have quit if Steve had come and said: "You guys don't get paid."

I think we would have still had a group and we still would have been working.

The original Mac came bundled with two programs: MacPaint and MacWrite

- Published27 January 2014

- Published2 November 2013

- Published8 March 2012

- Published6 October 2011