Cyberbullies: How best to tackle online abuse?

- Published

Youngsters are increasingly falling victim to cyberbullies

Hannah Smith, Izzy Dix, Rehtaeh Parsons - just a snippet of the tragic roll call of children who have committed suicide in the last year, with cyberbullying cited as a factor in their deaths.

The problem seems to be getting worse - according to the charity NSPCC, one in five children is now bullied online.

Meanwhile trolls, who send abusive messages to anyone they take an instant and often irrational dislike to, are now as established on the online scene as they once were in fairy tales.

It is time, says the UK's Anti-Bullying Alliance to call a halt to a trend that is "gradually chipping away young people's self-esteem".

"Cyberbullying increases isolation and impacts on mental health more than other forms of bullying," says Luke Roberts, national co-ordinator of the UK's Anti-Bullying Alliance.

Not alone

Karthik Dinakar was a victim of bullying and knows how hurtful it can be.

"I was very nerdy and different and it was difficult going through high school," he says.

Shortly after Mr Dinakar joined MIT as a researcher at its Software Agents Group, a teenager jumped off a bridge in New Jersey as a result of slanderous comments on social media.

The incident cemented in the researcher a desire to do something to help.

"That had an impact on me and resonated with my own experience," he says. "I set to work on a couple of algorithms to detect when someone is being mean."

The computer code matches, external what you write online to a database of commonly used words. It learns as it goes, using natural language processing, meaning that it can become pretty sophisticated at spotting even very subtle bullying.

Empathetic computing

Mr Dinakar says the system could be used by social media sites to flag potentially hurtful messages before they are sent.

"My observation is that we say things when we communicate online without pausing and thinking. So imagine if a box could pop up before you post saying 'Do you really want to send this?'"

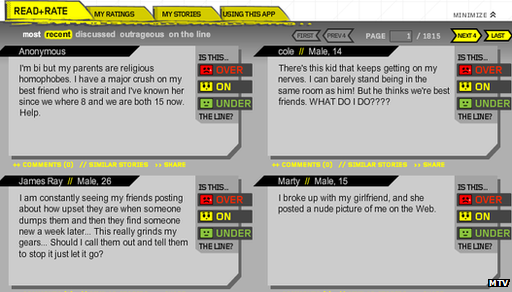

MTV uses an algorithm to screen messages posted to one of its websites

It is the digital equivalent of the little voice that everyone has in the back of their mind when they write something. Mr Dinakar calls it "empathetic computing".

Already the algorithm is being used by A Thin Line, an MTV website where teenagers share experiences of bullying.

So, for instance, if a visitor writes the words "girlfriend" and "dumped" in a message it can be identified as being about a relationship and placed in the relevant section. But if the post also includes terms such as "fatty", "slut" or "naked pictures", it can be flagged for review.

"A girl who has been harassed on Facebook can be matched to someone with similar experiences. It helps young people realise that they are not alone in their plight," explains Mr Dinakar.

He adds that the tool can also be used by moderators to sift through the content that needs the most immediate attention.

"These social sites have billions of users, and moderators have no way to prioritise the more serious cases of bullying."

Being mean

Such tools could prove invaluable, thinks Mr Roberts.

"It sounds pretty amazing," he says.

"Studies have shown that there is a lower level of empathy for the target in cyberbullying so anything that helps people reconnect with the fact that there is a human being at the end of the message is a good thing."

Do social networks need to do more to protect users?

As long as there are ways to communicate, bullies and trolls will exploit them but as we enter an age of all-pervasive network connection so too will calls for government, industry and community to act to limit the huge damage such people can do.

"Everyone has a piece of the puzzle. Industry can make safer online communities, young people can be educated better to deal with the issue, parents can offer better support rather than just banning their digital devices," says Mr Roberts.

"This is a solvable problem."

Report abuse

Recent experiences highlight the need for such a system.

Last month ex-footballer Stan Collymore accused Twitter of failing to deal with a torrent of abuse he had received.

Speaking on BBC Radio 4's Today programme he claimed that Twitter appeared to be more interested in making money than protecting its users.

"I accuse Twitter directly of not doing enough to combat racist/homophobic/sexist hate messages, all of which are illegal in the UK," he said.

In response Twitter urged anyone plagued by abusive tweets to use its new "report tweet" button.

"We cannot stop people from saying offensive, hurtful things on the internet or on Twitter. But we take action when content is reported to us that breaks our rules or is illegal," the firm said in a statement.

Human relationships

Facebook is also regularly accused of not doing enough to protect youngsters from abuse and cyberbullying.

Late last year, it beefed up its anti-bullying policy, offering youngsters on the site easy ways to contact an adult in their network to talk about the bullying.

Its bullying prevention hub , externaloffers suggestions for teens, parents and educators on how to address bullies and how to take action on the site.

It insists that it has "some of the most effective reporting tools available on the internet today".

"If people see activity on Facebook that makes them feel uncomfortable there are links on every page to report it so that we can remove it," the firm tells the BBC.

Mr Roberts thinks that such sites could do more.

"They say that bullying is unacceptable but they also say that they don't want to interfere with user content. It is as if their online space has been created without reference to human relationships," he says.

And while the new reporting tools are useful, they could be more effective.

"Even if young people report abuse it is often not clear what happens next," he says.

"Will they get a response in 10 hours, 10 days, a year?"

- Published28 January 2014

- Published12 December 2013

- Published17 August 2013

- Published16 August 2013