The internet through a light bulb

- Published

- comments

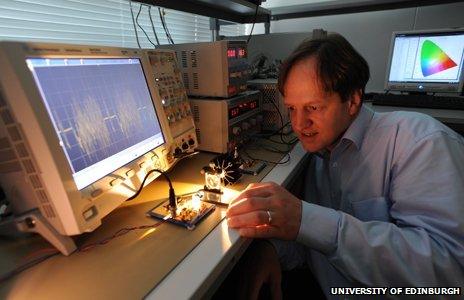

Professor Harald Haas demonstrates his LiFi technology to Rory Cellan-Jones

Imagine an office where every computer, mobile phone and tablet is connected to the internet not through an ethernet connection or via wi-fi but just through the overhead lights.

That is the vision that Professor Harald Haas lays out for me when he visits my office to demonstrate his LiFi technology.

Professor Haas has been working on this at Edinburgh University for some years, and is now running a company called Pure LiFi to try and commercialise the technology. The university itself has invested in a LiFi R&D Centre to try to kick-start an industry which might turn Edinburgh into a world centre for this technology.

Next week Professor Haas and a team which includes some of his former doctoral students will take their equipment to Mobile World Congress in Barcelona. So the demonstration in our office feels like quite a big deal - will it work, and will it impress?

They set up two laptops on a table, one with a conventional connection to the internet, linked to a piece of kit which is in turn connected to a conventional light fitting. The other computer has a bulky unit attached to it, effectively a light receiver. It's by making the light flicker very rapidly that data is conveyed from one computer to the other. It's a bit like Morse code," explains the professor, "but in a very sophisticated way, achieving very high data rates".

And lo and behold, it works, with the second laptop streaming a video which buffers and halts once I block off the light completely. Impressive then, but I have several questions about the practicality of getting LiFi adopted in the real world,

The clunky receiver unit looks a long way from being a finished product. The team admits there is much to do in this area, but with enough investment they believe they can miniaturise this process so that it will be a 1-sq-cm device that can be fitted into any smartphone.

Even then, there is a more important question - why when wi-fi works so well, do we need an alternative means of connecting to the internet? Wi-fi is indeed a great success, says Professor Haas, so much so that the radio spectrum is getting overcrowded: "We have deployed so many wireless access points that they interfere with each other and slow down the actual data rates. We need other pipes, fatter pipes - and light is just such a big pipe for wireless connectivity."

He also maintains that there are security benefits - light-generated internet connections do not travel through walls, so can not be intercepted like a wi-fi signal. The professor looks forward to a future where the much-hyped "internet of things" becomes a reality, where "there's wireless connectivity everywhere, your fridge talks to your toaster - this provides the means to achieve that".

It is a beguiling vision - but a lot more work needs to be done before we all start flicking a light switch to get connected.