Ted 2014: Meeting the real bionic man

- Published

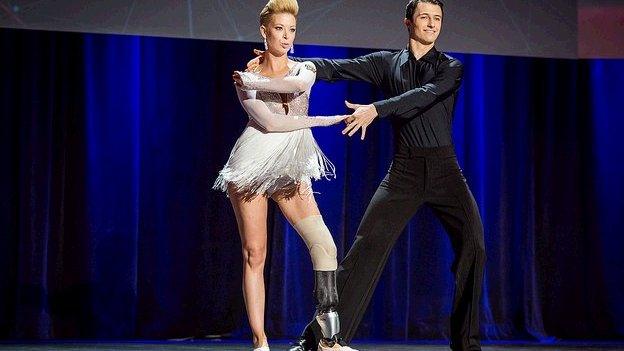

Boston bomb victim Adrianne Haslet-Davis took to the stage to dance with her bionic leg

When dance teacher Adrianne Haslet-Davis danced on the Ted stage, she got a standing ovation.

It wasn't the brilliance of the performance that got the audience on their feet but the fact that she was there at all.

It was the first time she had danced publicly since she lost part of her leg in the Boston bombings.

After the dreadful events during the Boston Marathon, she dreamed of dancing again.

That dream started to come true when she met Hugh Herr, head of the Biomechatronics research group at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology Media Lab.

He has dedicated years of his life to making bionic limbs that can outperform real ones.

His interest in creating such limbs is a personal one.

Hugh Herr is making artificial limbs as good as real ones

In 1982, Dr Herr - one of the US's most successful rock climbers - lost his way on a climb on Mount Washington.

Caught in a blizzard, he and his companion got lost and wandered for three days. With severe frostbite and on the verge of death, both were eventually rescued but there was a cost.

His companion had one leg amputated and Dr Herr lost both.

Not that you would know it as he strides confidently about the stage at the Ted (Technology, Entertainment and Design) conference in Vancouver.

He explained how the amputation affected him.

"I didn't view my body as broken. I saw it as a call to arms to eliminate my own disability and those of others," he said.

Cyborg man

He developed specialised limbs for climbing and returned to his sport "stronger and better".

From those relatively basic prosthetics made from metal, wood and rubber, he has now moved on to developing real bionic limbs.

The so-called BiOMs which his lab has made are unlike other artificial legs because they are able to emulate lost muscle function rather than rely on the remaining muscles to supply the energy to move the artificial one.

They are attached with synthetic skin that moves in the same way as real skin. The way that reflexes move the muscles in the missing limb are carefully modelled and the chips which control the limbs are embedded in the prosthetics.

For the prosthetic made for Ms Haslet-Davis, the team at MIT invited dancers to the lab in order to model the specific way that muscles work when dancing.

Users demonstrate the BiOM Ankle System by iWalk, which its makers say allows clients to walk at a natural speed

Bionic limbs and exo-skeletons are transforming lives for a huge number of people.

Nigel Ackland's arm was crushed in an industrial blender and after six months of operations and a lot of pain, he decided to have it amputated.

"The fit person I knew was replaced by a physical wreck and after two years, psychologically I was in a very dark place," he said.

His so-called Terminator arm, developed by BeBionic, was the world's most advanced when it was fitted in 2012.

It has been a life-changer, not just because he can now pour a beer and tie his shoelaces.

"Now when I walk down the street people will look me in the eye. A robot arm is kind of cool. No-one laughs at me any more - no-one laughs at a cyborg."

Nigel Ackland enjoys his cyborg status

Last year, Amanda Boxtel became the first woman to walk in a 3D-printed exo-skeleton.

It was a moment she had been waiting for since she had been paralysed in a skiing accident in 1992.

But unlike Nigel, she doesn't feel like a cyborg - her exo-skeleton actually makes her feel more human.

"I get a sense of euphoria every time I stand up," she said.

"When someone is sitting down the whole time not only does the spirit die but the body begins to die. We are not meant for a sedentary life."

Potential limited

She worked with EksoBionics and 3D Systems to devise the exo-skeleton, which she says is now like a "second skin".

In some ways these people are the lucky ones. There are some 20 million amputees around the world with no access to prosthetics.

Dr Herr has a meeting with the US government next week to persuade officials to make bionic limbs available to the patients who need them in the US.

He remains amazed about how technology limits human potential.

"I find it extraordinary that the shoe still gives us blisters," he said.

The technology he is working on might be far more complex than a shoe but he is hopeful that it can help eliminate the pain of disability.

"Every person should have the right to live their life without disability if they so choose," he said.

- Published27 November 2013

- Published5 February 2014