Next Silicon Valleys: Why Cambridge is a start-up city

- Published

Cambridge is an attractive place for tech start-ups

Cambridge has been dubbed Silicon Fen. Why have so many tech firms originated from here?

One of the problems with computers and tablets is that if you drop them, they tend to smash.

Make them bendable so you can, for example, roll them up and they become instantly more robust, as well as easier to carry around.

Start-up firm Cambridge Nanosystems is aiming to make this tech a reality, with its method of producing the key necessary ingredient - graphene.

The wonder stuff?

This virtually invisible material made from a single layer of carbon atoms, locked together in a strongly bonded honeycomb pattern, conducts electricity and heat and is incredibly light, but can be expensive to produce in large volumes.

However, Cambridge Nanosystems has developed a machine to convert gas waste, such as methane or carbon dioxide, into different types of carbon including graphene.

And it claims the efficiency of its method means it can turn 1kg of gas, about a bucket full, into more or less the equivalent volume of graphene in just one hour.

Dr Krzysztof Koziol, a director of the firm, says this could then be used to develop a conducting ink which can be deposited on surfaces ranging from plastic to metal and ultimately has the potential to print a touchscreen computer on a piece of paper or any other surface at low cost.

Cambridge Nanosystems converts gas waste into carbon

Knock-on effect

Like many of the tech companies that have earned Cambridge its Silicon Fen nickname, the company has been spun out of the city's renowned university.

Less than two years ago, Dr Koziol was a full-time academic - now he is juggling the start-up alongside his role as head of the electric carbon nanomaterials group at the university's department of material science.

This is not just a happy accident. In 1970, Cambridge's Trinity College set out to attract science-based industry to the area by setting up the Science Park on land it owned nearby.

It now hosts 100 companies, helping to create a knock-on effect in the surrounding area which has spawned some of the best-known names in the UK tech sector.

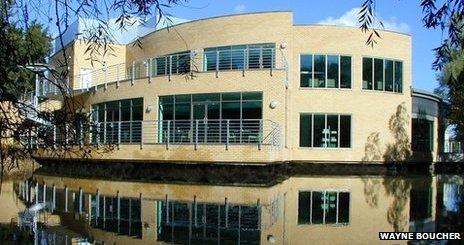

Cambridge Science Park opened in 1970

Arm Holdings, which designs computer chips used by the likes of Apple and Samsung's smartphones, originated here, as did Bluetooth chip creator Cambridge Silicon Radio (now CSR) and software firm Autonomy, which HP controversially paid $10bn (£6.7bn) to buy in 2011.

Cambridge itself is now ranked as one of the top three "technology innovation ecosystems" in the world, according to a recent international survey, external.

Conflicting worlds

The worlds of commerce and academia are not always easy bedfellows, however.

William Webb, chief executive at Weightless SIG, which runs a wireless technology for machines which he was instrumental in designing as well as deputy president of the Institution of Engineering and Technology, says there are often tensions over intellectual property rights or patents when research conducted at the university is commercialised.

Firms are often spun out of successful research at Cambridge University

"Universities are not directly driven by money. Start-ups, consultancies, commercial companies absolutely are," he adds.

But Dr Damian Gardiner, co-founder of another Cambridge spinout, Ilumink, has benefited financially from his connection to the university.

'Real world' use

He received an enterprise scholarship from the Royal Academy of Engineering to help him develop his research in printable laser technology into a commercial product aimed at fighting fraud.

The firm uses an inkjet printer to print a liquid crystal laser using fluorescent dye with a specific pattern and colour combination on to a wide range of surfaces including plastic, paper, metal and glass.

Visible when checked by a second laser, the technology could be used to make sure a high-value item, such as alcohol or medicine, is the real thing.

"I wanted to see how technology could be taken from the lab and actually used in a real world, a product that would be useful to people," he says.

Ideaspace, which provides office space and resources for people looking to start a new firm in Cambridge, aims to help people do exactly this.

Aqdot's "shrink wrap" tech can encapsulate tiny droplets

Its criterion for membership is that the new business has to positively affect the lives of a million people within three to five years.

Founded in 2010, it is already working with 80 companies.

"What we're really trying to do is provide a focal point for the start-up community to gather in one place to increase the chances of serendipitous interaction," says Ideaspace director Stewart McTavish.

He believes that the university's academic freedom helps commercially. "They're permitted to experiment and if they fail that's fine as well as long as they do it in the right sorts of ways."

One of its members is Aqdot, which was spun out from the university in 2012.

The firm has created a "shrink wrap" technology which can encapsulate tiny droplets of active ingredients to be released precisely when needed.

The technique could be useful in industries such as agriculture - to release weedkiller after a pre-determined amount of sunshine, for example - or in cosmetics to release dye directly to the follicle that requires it.

"When you bring academia and industry together that's when you create exciting opportunities," says co-founder and chief scientific officer Dr Roger Coulston.

This feature is based on a series of television interviews by Neil Koenig for the BBC's Next Silicon Valley series.

- Published17 July 2013

- Published30 April 2013

- Published19 March 2013

- Published30 November 2012

- Published20 March 2012

- Published8 March 2012