Data-stealing Snoopy drone unveiled at Black Hat

- Published

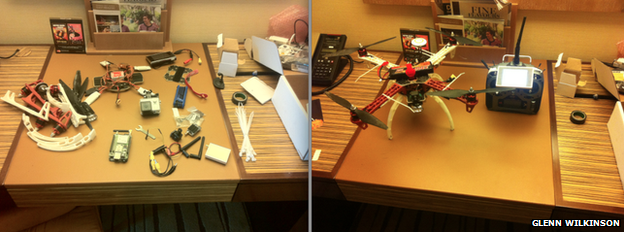

Glenn Wilkinson uses a quadcopter drone with the Snoopy software built inside to gather smartphone data

Security firm SensePost has unveiled its Snoopy drone, which can steal data from unsuspecting smartphone users, at the Black Hat security conference in Singapore.

The drone uses the company's software, which is installed on a computer attached to a drone.

That code can be used to hack smartphones and steal personal data - all without a user's knowledge.

It does this by exploiting handsets looking for a wireless signal.

Glenn Wilkinson, who developed Snoopy, says that when the software is attached to a drone flying around an area, it can gather everything from a user's home address to his or her bank information.

"Every device we carry emits unique signatures - even pacemakers come with wi-fi today," Mr Wilkinson tells the BBC.

"And - holy smokes, what a bad idea."

'The machines that betrayed their masters'

Many smartphone users leave the wireless option constantly turned on on their smartphone. That means the phones are constantly looking for a network to join - including previously used networks.

"A lot of [past] network names are unique and it's possible to easily geo-locate them," says Mr Wilkinson, who explains Snoopy uses a combination of the name of a network a user is looking for as well as the MAC address that uniquely identifies a device to track a smartphone in real-time.

Snoopy can identify the exact location and user information of a specific smartphone

Beyond that, Snoopy demonstrates how someone could also impersonate one of those past networks in a so-called karma attack, in which a rogue operator impersonates a past network that a user then joins, thinking it is safe.

Once the user has joined the disguised network, the rogue operator can then steal any information that the user enters while on that network - including e-mail passwords, Facebook account information, and even banking details.

This is why Mr Wilkinson says that smartphones and other devices that use wireless technology - such as Oyster cards using RFID (radio frequency identification) or bank cards with chips - can betray their users.

'Am I on candid camera?'

Mr Wilkinson - who began developing the Snoopy software three years ago , externalas a side-project - gave the BBC a preview of the technology ahead of its release.

Pulling out a laptop from his bag, Mr Wilkinson opened the Snoopy programme - and immediately pulled up the smartphone information of hundreds of Black Hat conference attendees.

With just a few keystrokes, he showed that an attendee sitting in the back right corner of the keynote speech probably lived in a specific neighbourhood in Singapore. The software even provided a streetview photo of the smartphone user's presumed address.

SensePost has used the Snoopy software attached to cheap commercial drones like DJI's Phantom

"I've gathered smartphone device data from every security conference that I've been at for the last year and a half - so I can see who was at each event and whether or not they've attended multiple events," says Mr Wilkinson.

He then shows this data to conference attendees - who often ask, when presented with a photograph of their home or office, if they're on candid camera.

Bringing awareness

Mr Wilkinson is quick to acknowledge that the Snoopy software is not new technology - but rather, just a different way of gathering together a series of known security risks.

"There's nothing new about this - what's new is that Snoopy brings a lot of the technology together in a unique way," he explains.

For instance, the Snoopy software has been ground-based until now, operating primarily on computers, smartphones with Linux installed on them, and on open-source small computers like the Raspberry Pi and BeagleBone Black.

But when attached to a drone, it can quickly cover large areas.

"You can also fly out of audio-visual range - so you can't see or hear it, meaning you can bypass physical security - men with guns, that sort of thing," he says.

It's not hard to imagine a scenario in which an authoritarian regime could fly the drone over an anti-government protest and collect the smartphone data of every protester and use the data to figure out the identities of everyone in attendance.

Mr Wilkinson says that this is why he has become fascinated with our "digital terrestrial footprint" - and the way our devices can betray us.

He says he wants to "talk about this to bring awareness" of the security risks posed by such simple technologies to users.

His advice? Turn off the wireless network on your phone until you absolutely need to use it.

- Published6 January 2014

- Published4 December 2013

- Published1 November 2013